It could’ve been scheduled for any day, but Zeinab Rezaie’s flight happened to be scheduled for that day.

The night before Kabul fell, Rezaie and her family had been glued to the chaos on the news, and in the early morning, as she and her husband, Ali Karimi, drove toward the city center on the way to the airport, their new reality became clear. Everything was suddenly different. Afghanistan’s capital had always bustled with commuters at this early hour. Now it was nearly deserted. Storefronts were shuttered. Only the bearded young men from the mountains, with their big guns, walked the streets. “The face of the city was changed,” Rezaie says.

For the young couple, the drive was tense; there was no telling what might happen if their car was stopped at one of the new makeshift checkpoints. Rezaie had made sure to cover her hair that morning, and Karimi wore traditional Afghan garb. Rezaie watched the Taliban fighters stare into every car, stopping and searching a handful. “Maybe they were looking for former soldiers or for guns or for people in uniform,” she says. She didn’t know for certain. Rezaie had spent years working with a foreign non-governmental organization (NGO), which she suspected could make her a target. And: “I don’t know what would have happened to me if they had learned I was [traveling] to the U.S. on a visa,” she says.

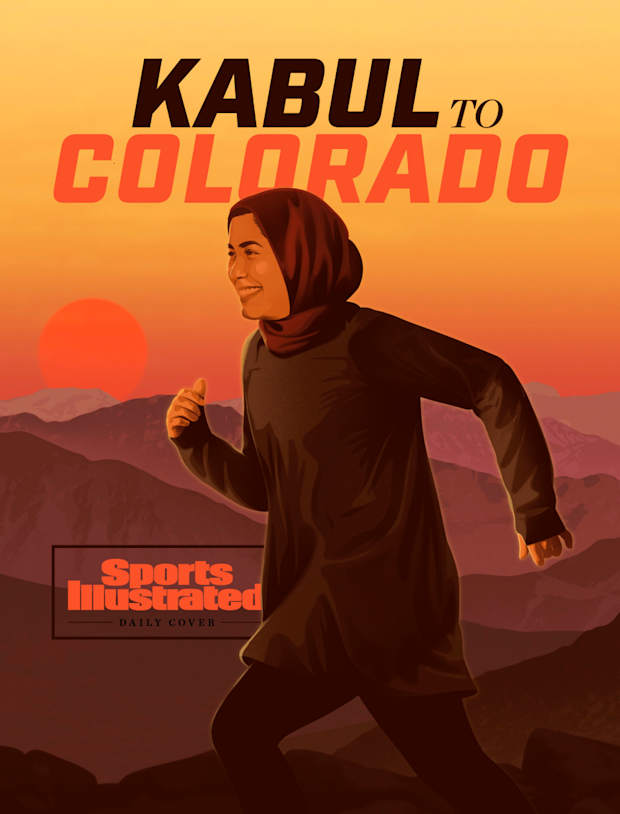

Illustration By Avinash Weerasekera

Arriving at a checkpoint, Rezaie and Karimi lowered their eyes as a Taliban soldier looked them over and, after a bated breath, waved them on. Their car drove forward, and soon enough they were at Hamid Karzai International Airport, where more Taliban soldiers with raised guns tried and failed to keep order as masses of scared citizens swarmed the entrance.

“I remember everything from that morning,” Rezaie, now 27, says of Aug. 16, 2021, the day after the Taliban seized Kabul’s Presidential Palace (following President Ashraf Ghani’s fleeing the country). In less than two weeks, the Taliban had captured 26 of the country’s 34 provincial capitals, returning to power 20 years after the U.S. ousted the fundamentalist Islamic militia. Rezaie walks through the early hours of that fateful day with precise detail, but one image remains clearer than the rest. Beyond the fear and the conquerors’ ineptitude, both burned into her memory, she remembers most vividly a pile of shoes outside the airport’s front doors. The incongruity of it all haunts her.

“Why were they there?” she still wonders. “Where were their owners?”

There was no time to find out. Rezaie’s world had changed overnight. She had a Fulbright scholarship that started a week later, at Colorado State, and she had tickets that day on a flight to Denver, with a layover in Istanbul.

She entered the throng. Then she started to run.

Rezaie still remembers the first time she went for a jog. This was 2015, and she’d recently accepted a scholarship to American University of Afghanistan, on the southern fringe of Kabul, with the mountains in the distance. A representative from the university had identified Rezaie as a standout high school student in the town where she grew up, Herat, by the Iranian border. Now, she found herself a bit shocked in the capital city, with its 4.5 million residents and comparatively open culture. In Herat, women concealed their hair and hid their bodies, often under long veils. In Kabul, though, they wore dresses of varying lengths, and some chose to wear their hair uncovered. Public spaces were dominated by men in Herat; in Kabul, Rezaie saw women at the markets and on her morning commute; even, sometimes, on bikes.

The university assigned Rezaie a pair of roommates in the dorms, and she remembers how these two young Afghan women would go out for jogs each morning. “I’d never heard of or seen girls running in the streets,” she says. “It was so cool for me. I really wanted to join them and to experience that.” So she did.

Progressive as Kabul seemed in this period, running brought risk for an Afghan woman. The new friends carried pepper spray when they ventured out. One morning, a man on a bicycle followed them, screaming: “You should be at home! An Afghan girl should be at home! You’re a bad example for other Afghan girls.” Rezaie says he lunged at them, attempting to punch one of the roommates.

Still, Rezaie felt a new sense of freedom on these morning jogs. “I was excited about running, and when you get excited about something, you do not have fear,” she says. “I was not afraid of anything.”

Courtesy of She Can Tri

Rezaie learned about Free To Run, a nonprofit started by United Nations humanitarian lawyer Stephanie Case, who was at the time based in Kabul. The NGO works to drive social change in areas of conflict by helping adolescent girls and young women advance their leadership and wellness through running and outdoor adventure, in part by shuttling them to safe areas where they can hike or jog comfortably. And in that relatively safe zone Rezaie went from a participant to a program manager, introducing others to distance running. In short, “Zeinab found her voice,” says the Canadian-born Case. “[She] dared to attempt athletic feats that few would take on.”

Among those feats: the 2018 Gobi March ultramarathon, a seven-day, 155-mile footrace across central Mongolia. It was in Rezaie’s preparation for that race, in Kabul, that she met Jackie Faye, a blond-haired, blue-eyed military journalist who’d recently taken a post at the NATO headquarters not far from the U.S. Embassy. Faye, then 32, was in the middle of attempting to complete six Ironman races on six continents in one year, and Rezaie began training with her at the NATO compound.

As part of Faye’s job, she spoke frequently with Afghan citizens, but it was those runs with Rezaie that really taught her about day-to-day life for a woman in Kabul. “I interviewed plenty of women … but it was always in a very serious setting,” she says in an accent she hasn’t quite lost from her small-town South Carolina upbringing. “It wasn’t like I got to ask them about sex, or their daily lives, or any of these things that, as an American woman, I was very curious about.” Her runs with Rezaie became a window into the realities of Afghan life, which foreign journalists were often shielded from.

Eventually Faye started a nonprofit of her own—She Can Tri, which works to get women in conflict zones involved in sports—and recruited a group of four Afghan women she would train to compete in triathlons. In January 2019, Faye flew that group, including Rezaie, to watch an Ironman triathlon in Dubai, where she bought them each burkinis and gave them each their first swim lesson. “I was the worst coach ever; I totally started crying,” Faye says. “They were scared of the water. We were holding hands, counting to three and going under. Here I was thinking, I want these girls to be able to compete in a triathlon in a year. I was like: How are we going to get there?”

The first thing Rezaie noticed as she began her run through the airport that morning in August 2021 was that there was no one left to keep order. No security guards. No airport personnel. Just mayhem.

She sprinted alongside terrified Afghans desperate to escape before Taliban fighters remade the country in their image. The concourse was a raging river, bubbling from the heat of anxious energy. Every doorway became an eddy. “We passed through the gates with a lot of pushing,” she says. “It was so difficult, because everyone was trying to pass the doors.”

Rezaie remembers her husband saying they should go home, that they’d be killed in the madness. “But I said, ’No, let me push through.’” When finally they managed their way to the tarmac, Rezaie was met by a barbed-wire fence, guarded by American soldiers. She called Faye, with her NATO ties, who told her to go talk to the soldiers. Rezaie had a ticket and a passport and a visa, after all—she had every right to be on one of the planes. “But they were not listening to me,” she says. “And people were pushing from behind. I hurt my hands and my legs with the barbed wires. My clothes were torn.”

Wakil Kohsar/AFP/Getty Images

Faye, meanwhile, made contact with an Italian special forces officer whom she knew to be stationed at the airport. He drove across the tarmac and found Rezaie and spoke to the American soldiers, who let him take her through. Rezaie, as she left, waved back to her husband, nothing more—“It was so quick,” she says—failing to foresee the months that would pass before she reconnected with him.

Rezaie, in the end, had run a hellish endurance race, pushing and shoving and squirming her way through a barbed wire divide. If she hadn’t been so bold as to try, or strong enough to reach the front of the pack, she would not have reached her goal.

But where did that well of bravery come from? “It’s not that I have been always brave,” she says. “Sometimes I didn’t have confidence in myself. Sometimes I really cried. I was panicking. I didn’t have the time to think, What is good, or bad? I was just doing things unconsciously.”

Amid waves of adrenaline and chaos, she continued forward, her legs churning. Her mind remained startlingly clear.

To embark on a graduate program 7,000 miles from home can be jarring. To do so while your family back home lives under Taliban rule is something else. Rezaie watched from afar as the women closest to her were made to retreat from the workforce, their lives shrinking to fit within the walls of a home. She watched on TV and read about bombs killing girls at a Hazara school and the Taliban beating women who protested the massacre. She was surrounded by striking beauty in Fort Collins; but it felt wrong to relish in it.

At Colorado State, Rezaie was buried under the weight of what she’d left behind as she began her Impact MBA degree, designed to teach students to create societal good through business. Two months after she left Kabul, Karimi was evacuated to a refugee camp in Abu Dhabi, as was Rezaie’s younger brother, Mahdi. Karimi was eventually allowed to join Rezaie in Colorado, last June, but Mahdi remains at the camp, “stuck in limbo, doing nothing,” Rezaie says. “He can’t continue with education. He can’t work. It’s difficult to imagine how people in that camp are passing their days—the days and nights are all the same.”

Then there’s Rezaie’s older sister, who worked full-time as a midwife, and then for a humanitarian aid organization, before the Taliban took back power, and who today spends her days tending to her home. (To protect those still in Afghanistan, Rezaie asked not to use her family members’ names.) “[My sister] is an example of a woman who lost all her rights—she was free to do whatever she wanted, but now she cannot work,” says Rezaie. “She’s always saying, ‘I’m depressed. I’m bored of doing nothing. I want to be productive. I want to make a change.’ But it’s not possible.”

As Rezaie’s school year began, she questioned herself: Why am I here instead of them? The guilt became suffocating. Fort Collins was laced with gorgeous trails and bike paths; there was no trace of the soot that muddied Kabul’s air. But when friends invited her out, she sequestered herself. “I was feeling I don’t deserve it,” Rezaie says. “My family and friends back in Afghanistan, and other Afghan women, they do not have these opportunities. They cannot be happy. I was trying to avoid being happy because I was feeling guilty.”

Calling Colorado from Kabul, Rezaie’s sister told her to “grab the opportunity, but also not forget about them and to be a voice.” Says Rezaie: “I’ve tried to be a voice for Afghan women and girls.”

She’s not alone. Rezaie’s friend Zahra also left Afghanistan for the U.S., one week earlier in 2021, to start a Fulbright program at a college in the northeast. Zahra (who asked that identifying details be excluded, to protect her family) now works as a finance counselor at the college, but she remains flooded with worry for her family members, some of whom attend the Hazara schools targeted by the Taliban. “I cannot keep my mind peaceful,” she says. “I think every day, every moment of my life, about them. Emotionally, it’s breaking me.”

Fighting back tears, she describes a recurring dream: She’s in her old kitchen in Afghanistan, cooking bolani, a traditional stuffed flatbread. Her entire family is talking, laughing, preparing to eat the feast. But it’s not real, and may never be again. “To have all my family members around, that seems, for me, impossible,” she says. “And I think that I cannot live without [them].”

Separated from loved ones, Zahra and Rezaie have together found comfort in new connections and experiences. In 2020, both traveled with Faye to the United Arab Emirates to compete in the Ironman 70.3 Dubai. Rezaie was the stronger swimmer, so she reached her bike much faster than Zahra, which left Faye having to decide whether to race alongside Zahra, the stronger biker and runner, or Rezaie, who had the lead. Ultimately, Faye stuck with the leader. “But in hindsight,” she says, “I wonder if I had stayed with Zahra I could have gotten them both across the finish line.”

Courtesy of She Can Tri

Zahra, in the end, missed a checkpoint by two minutes, a disqualification. Rezaie, meanwhile, crossed the finish line in 7:58:07, becoming the first Afghan woman to complete an Ironman 70.3 (or half-Ironman) and earning her a spot at the 70.3 World Championships.

Then came a wait. And doubt. The championships were postponed for COVID-19, and it became difficult for Rezaie to focus on her weekly training. Was it selfish to prepare for a race at a time like this?

She thought about how running had connected her to Case and Faye. How those two women had helped her secure the Fulbright and guided her onto that plane. Plus: Rezaie could be a symbol, couldn’t she? An Afghan woman crossing a finish line had to mean something for those who weren’t even permitted to cross through the front door of a school.

So, despite the psychic pull back home, and despite the mountains of work, Rezaie found time to train. She wasn’t as fast as she’d hoped, or as strong, but she had a lifetime of endurance training.

“I don’t want the world to forget about Afghanistan,” Rezaie says. “That’s why some of us are trying to raise our voices.”

Escorted by an Italian special forces soldier to a Turkish Airlines plane, Rezaie waited at the airport again, this time behind who she discerned to be foreigners and highly connected Afghan citizens. When she reached the front of the line, she was told by several men she believed to be Turkish diplomats (but who never identified themselves) that while, yes, this was her flight, and, yes, she had a ticket, the commercial plane had been chartered for evacuees. Relief only came when another official-looking man pulled her aside and assured her that she’d be allowed on the plane.

On board, Rezaie says she found her seat and waited for hours. She tried not to look at the mayhem outside, where thousands of desperate Afghans ran around the tarmac, trying to force their way onto a plane—“It was so difficult to see my countrymen and women in that situation.” She couldn’t help but absorb the tragedy all around her. Through her small window she watched as Afghan men climbed onto the wheel hub of a U.S. military plane. At the last moment, before the military plane took off, she says she turned away, but others on her flight filmed with their cellphones, the footage of the falling men later becoming a symbol of the day’s horrors.

“I don’t judge [the men who climbed on the plane],” she says. “Maybe they were panicking. … Maybe they didn’t know what was going to happen to them. … Maybe they were thinking that their lives mattered, and that the pilot knew they were sitting on the [wheel] and that he would not fly.”

Wakil Kohsar/AFP/Getty Images

After several hours, Rezaie’s plane finally taxied off the runway in Kabul. Airborne, she remembers how the few Afghan men and women onboard cried out—most of the passengers were internationals—and how she wondered to herself: What will happen to our families? What will happen to our country? Will we ever be allowed to come home again?

“I have heard that when someone dies, for a moment he remembers everything in his life—all the memories, bad or good,” Rezaie says through tears, a year and a half later. “When the airplane took off, everything came into my mind for a few seconds: my family, our lives, our friends, our memories. And not only the past, but also our future.”

Rezaie arrived at the starting line of the 2022 Ironman 70.3 World Championships before dawn last October, and she shivered in her wetsuit and swim cap, sipping coffee with some 1,900 other women as they waited to dive into the frigid Sand Hollow Reservoir. They would each swim 1.2 miles, then bike a hilly 56-mile course before running two 6.55-mile loops to the finish line on Main Street in downtown St. George, Utah.

Rezaie’s name was finally called in Wave 10, the second-to-last group, and she dove into the 62-degree water. “I was stressed,” she says. “I was afraid.” Early on, she got kicked in the head. A swimmer grabbed onto her foot. She felt panicked, but she let the mass of racers pass by and settled into her stroke, eventually finishing in 53 minutes. Not bad, she figured, for someone with almost no swimming experience.

Back on land, powered by a rush of relief, she remembered the advice Faye had shared about the biking segment. Keep your speed up, but also don’t forget to enjoy the scenery. And that Friday in Utah was striking: the red sandstone cliffs, the desert vistas.

Around mile 17, Rezaie’s calves began to cramp up—first the left, then the right. She tried positive affirmations, then started problem-solving, chugging down electrolyte water and stretching as she peddled. Forty miles in, still aching, she came upon the section she’d been dreading: Snow Canyon Parkway, a four-mile stretch that climbs 1,100 feet. She pedaled on, worried that she’d miss her checkpoint goal, asking herself, What does this all mean if I don’t finish the race?

“I was thinking, I cannot do it; I cannot meet the cutoff time,” she says. “I was feeling alone.”

On that unending ascent, her mind advocated for her throbbing body. You can quit, can’t you? Don’t you have every excuse to fail? She hadn’t had the time to train like she wanted. Her master’s program was taxing. She was in a personal purgatory, waiting for approval on the asylum status she’d applied for, which would allow her to remain in the U.S. And there was that insurmountable, unremitting stress of a family left behind.

Donald Miralle/Ironman

And the other racers? They’d all learned to swim and to bike when they were kids. Many had completed dozens of triathlons. But not Rezaie. The hill was steeper for her, wasn’t it?

She peddled, but it felt like she was barely moving at all. It felt impossible that she’d reach the top before time ran out. Why not quit? What are you trying to prove?

Halfway up Snow Canyon Parkway, when the voice in her head had nearly persuaded her, Rezaie says she remembered why she’d taken on this challenge in the first place. “If I was only racing for myself, I was O.K. quitting,” she says now. “But the race was not for myself. I was thinking: It’s my responsibility to finish, to represent the women of my country.”

She pushed, and she crested the peak, barely making her cutoff time at the next checkpoint. Rezaie savored the downhill, but she knew she couldn’t coast; she had to make up for lost time.

It would all come down to the run: two laps adding up to a half marathon. And the pain was by now all-encompassing. Rezaie’s cramps had grown more acute. Each step felt like a hammer to the bottom of her feet. There were still runners on the course during her first lap, but by the second it was nearly empty, leaving Rezaie to soak in a putrid brew of hopelessness and loneliness. Faye, meanwhile, watched nervously as a caravan of Ironman vehicles trailed her friend, ready to scoop her up if she fell too far behind. Not that Rezaie—who’d forgotten her watch on her bike—knew how close she was to being done. She just remembers seeing Faye’s stressed face on the sideline. And how much it annoyed her.

As Rezaie finally approached the finish line on Main Street, with all the weight of the past 15 months dragging her legs, an announcer told the crowd about Rezaie’s story. The clock ticked 8:28:57 when she finally crossed, in 1,825th place. She was the last woman in the field, but she’d beat the cutoff by 63 seconds.

At some point she was handed an Afghan flag, which she eventually draped over her shoulders.

Donald Miralle/Ironman

even in her accomplishment—becoming the first Afghan woman to conquer the Ironman 70.3 World Championship, despite the chaos of her exodus and the demands of her MBA program—Rezaie can’t shake a question she’s been struggling with all year: “Why should I be the first?”

She knows she’ll never be the fastest runner or the best biker. Certainly not the most talented swimmer. She knows that if every Afghan woman had the freedom to compete, she would not be her country’s best female triathlete. Not even close. “We could do much better than me,” she says.

But Rezaie’s race began long before the starting line. To be first is just as much about pushing through all that came before. The bravery to take that initial run, and to keep running. The will to take on a marathon two years after her first jog. The guts to dive into open water one year after learning to swim.

Which she recognizes. The pain she has experienced in her life, the tolerance she’s built, she knows few can match. And she tapped that well to reach the finish line in St. George.

In that way, her Ironman was easy. The finish line is a finite point—a fixed location where the pain will end. For so many women in her country, though, a finish line does not exist. Recently, Taliban leaders, on top of banning Afghan women from attending schools, gyms or public parks, have refused to allow female aid workers into the country. “The problems feel never-ending,” Rezaie says. “There should be a finish line. … Everyone should help the women and girls in Afghanistan try to cross that finish line. … We are fighting for very basic human rights.”

It’s difficult for Rezaie to relax these days. Her brother remains stuck in a refugee camp, far from home. Her family is still trapped in Afghanistan, which is rapidly degenerating under Taliban rule. Rezaie cannot apply for her parents to join her in the U.S. until she receives citizenship herself, which will take at least five years. Meanwhile, she continues to wait for a decision on her asylum status.

In January came news that her sister is expecting a baby girl, but the siblings are terrified about the new reality the infant will be born into. “I am looking for help to get my family out,” Rezaie says. For hours every day, she tries to mentally assemble the puzzle that is her family’s future, but the pieces feel hopelessly scattered. She says that only when she’s running can she imagine a peaceful resolution to it all.

Exertion, even at the point that it reaches pain, delivers a mental reprieve. “It is painful, but it’s physical pain—painful at the moment, but momentary. It will go away,” she says. “I feel I can endure, in life and in sports.”