In November 1956, three people gathered in a converted Connecticut barn to take LSD, a powerful psychedelic drug that was legal at the time.

The children had just been put to bed upstairs. In the converted barn's main room, Elizabethan ballads drifted through smoke-thick air as someone scattered chrysanthemum petals across a sheepskin rug. The flowers seemed to reanimate in the candlelight, blooming and dying with each flicker. Two of the participants lay hand-in-hand in ecstatic communion, while a third sat rigid and apart, his detachment crumbling into barely contained fury.

By midnight, everything would shatter.

One participant spiraled into visions of nuclear war. Another transformed into a 10-foot colossus of feminine power. And in the space between these extremes, a marriage began its quiet collapse.

The aftershocks would reverberate through three generations of Britain's most celebrated intellectual family, the Huxleys, leaving wounds that simmered in private letters for more than sixty years.

It’s fitting that this story should be told on Bicycle Day, the annual commemoration of April 19, 1943, when Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann first rode his bike home under the effects of LSD — and ushered in the modern psychedelic era. Nearly 14 years after that inaugural ride, the drug had drifted from the lab into the lives of artists, seekers and intellectual elites like the Huxleys.

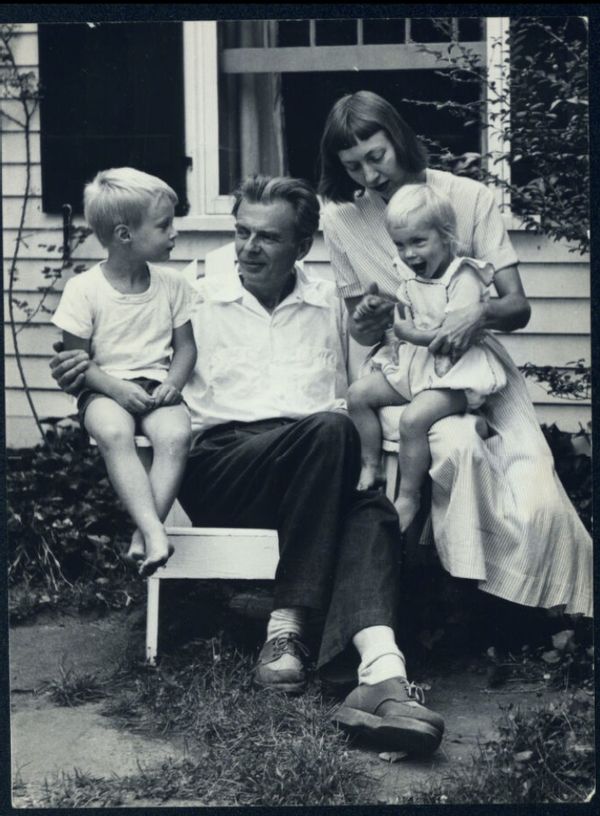

The trip's architect was Dr. Humphry Osmond, the psychiatrist who had first guided Aldous Huxley — the author of “Brave New World” and “The Doors of Perception” — in experiments with mescaline. and coined the term “psychedelic.” His subjects that evening were Aldous' only son, Matthew Huxley; Matthew's wife, Ellen; and Francis Huxley, Matthew's cousin and the son of biologist Julian Huxley.

The seeds of the LSD trip were planted a year earlier, in the summer of 1955. Aldous Huxley, recently widowed and struggling with his grief, came to stay with Matthew and Ellen. During those long Connecticut evenings, as Ellen read to him (his eyesight was failing) and fashioned him clothes from old trousers, Aldous began sharing intimate confessions about his psychedelic experiences. The drug, he told her, had finally broken through his English reserve: “It was the first time I could really cry.” LSD “hits you where you are most blocked,” he explained, as cited in David Dunaway’s unpublished interview with Ellen Huxley from 1985.

Ellen was already straining against the constraints of domestic life. A frustrated filmmaker trapped in the role of housewife, she found herself increasingly alienated from Matthew, who seemed content with their conventional existence. When she pressed Aldous to help them experience LSD for themselves, he demurred. Undeterred, she reached out directly to Osmond, who had been following the fault lines in the younger Huxleys' marriage with professional interest.

By 1956, Osmond had developed what he considered an ideal protocol for psychedelic experiences, rejecting sterile hospital environments in favor of comfortable, aesthetic settings. The converted barn, with its rustic beams and carefully curated music collection, seemed perfect. More intriguing was the group's dynamic: Matthew, the dutiful son carrying the weight of the Huxley legacy; Ellen, pushing against the boundaries of her prescribed role; and Francis, fresh from publishing his anthropological study of an indigenous Amazonian tribe, embodying everything his cousin Matthew was not — rootless, adventurous, unconstrained by convention.

The evening began at 7:15 p.m. It was the eve of the 1956 presidential election fought between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. The Huxley troupe took their careful doses of Sandoz LSD in liquid form. Francis, who would later produce 14 pages of meticulous notes, felt it first: “Something begins to take charge of me, an intelligent automatism.” His body dissolved into the surroundings, “swimming” rather than walking through space. Someone had the unsettling idea to play a recording of Aldous reading from his novel “Time Must Have a Stop” — a passage about a character's journey into the afterlife. Though he was 3,000 miles away in California, Aldous' distinctive voice filled the room, his baroque prose about “a vast ubiquitous web of beknottedness and diversity” sending Francis into fits of uncontrollable laughter.

Then came the moment that would alter everything. As Elizabethan folk songs replaced Aldous' voice, Francis took a chrysanthemum and held it to Matthew's nose before scattering its petals across the sheepskin rug. “I scatter them in the air itself,” he wrote, “and the music becomes full of flowers.” Matthew, perhaps sensing the evening slipping away from him, reached for his wife's hand. But it was Francis and Ellen who found themselves transported, dancing as flowers bloomed in the air around them.

Ellen's account burns with the electricity of the moment: Matthew still detached, being scientific and “taking the group pulse.” “We hated him for not giving in to the joy,” she wrote. “He seemed to sit on the rim of the world, and we others in the bottom of the cup. Why didn't he laugh? Francis and I lay on the floor, hand in hand, our noses pressed into the sheepskin rug — this is pure joy.”

Matthew's response would turn the euphoria to ash. He left the room, returning with a metronome whose loud, mechanical clicking lacerated the otherwise-fine mood being created by a Bach record on the turntable. His stated purpose — ”to set our experience against an objective reality” — was transparent in its desperation. As the harsh clicks fought against the music, Osmond, the experienced guide, was forced to intervene. Francis dismissed the gesture as “absurdly pompous,” but the damage was done.

The evening plunged deeper into darkness. A wave of what Francis called “telepathic communication” swept through the group. It brought violent dissolution. The men, as though seeking a scapegoat for the chaos, turned collectively on Ellen.

“They all turn on me, scrapping like dogs, men against women,” she wrote. Humphry's demand — “why did you do it?” — triggered a transformation. Ellen felt herself grow “10 feet tall and very thin and very powerful and malignant.” Francis, his earlier tenderness forgotten, saw her as “the old yellow hag who plots destruction and brings about the downfall of the world.” Ellen, rather than shrinking from their attack, embraced her power, becoming “full of poison which is reinforced by the drinking of the lemonade.”

As midnight approached, the psychic tension in the room crystallized into apocalyptic terror. When Osmond casually remarked that “Things must come to an end at midnight” — meaning simply the trip — Francis spiraled into nuclear paranoia. Convinced they alone could prevent global annihilation, he frantically wondered: “Do I pick up the phone and call Eisenhower and [Soviet Prime Minister] Bulganin?” The group, desperate to contain the mounting chaos, formed a circle and joined hands — all except Matthew, who remained outside their ritual. Francis watched his cousin with growing horror: “He reminds me of my brother and then slowly turns into him ... he is the Other, and his face takes on a menacing symmetry.”

The breaking point came in what Francis would later call an exorcism. “Damn you, Matthew, damn you; I hate you, I hate you,” he shouted across the divide, adding with acid-logic, “It is only by saying this that I can be certain I do not in fact hate him.” Only Osmond's intervention — a steady mantra of “Together, together” — and the administration of niacin finally brought the group back to what Francis called "drab reality," leaving him with the bitter taste of failure, “knowing that we have, after all, failed to change the world as we set out to.”

But the real aftermath was just beginning. The next morning, after Matthew left for work, Ellen and Francis became lovers. The LSD had pulled back a curtain that couldn't be drawn again. When Francis' parents, Julian and Juliette, visited that weekend, Ellen's letter to Osmond practically vibrated with barely contained secret joy: “They were obviously nonplussed by Francis and me ... I'm sure that Juliette thought we were living together ... as indeed we were, living together.” Her emphasis carried the weight of revelation: “She had married the wrong Huxley,” as quoted in Ron Roberts and Theodor Itten’s “Francis Huxley and the Human Condition.”

For three years, the affair simmered beneath the surface of family life. It reached its breaking point in 1959, when Matthew found them together in their Brooklyn Heights home. Francis was recovering from malaria contracted in Haiti, with Ellen as his nurse. Matthew's ultimatum was stark: Francis must either marry Ellen or leave. It was a miscalculation.

Francis chose exile, moving in with a filmmaker friend nearby. The cousins never spoke again.

Matthew and Ellen never mentioned the trip to their two children, Trev and Tessa. Trev only learned of it in his 70s, when the letters and trip reports were published in “Psychedelic Prophets” in 2019. When Aldous learned of the marriage's collapse, a letter to his son Matthew exposed his own buried guilt: “I know very well what you mean when you talk about dust and aridity and a hard shell that makes communication in or out extremely difficult ... Unfortunately, when you were a child, I was predominately in the dust-crust stage, and so must have been a pretty bad father.”

The acid-induced crisis had cracked open not just a marriage, but the emotional fortress of English reserve that had shaped both father and son. Matthew, as his own son Trev would later reflect, had always “felt mauled by Aldous and burdened by his massive family legacy,” as he said in a video interview in December, 2023.

But the collapse of Matthew’s marriage would bring them closer together.

Francis, in a remarkable unpublished letter to his parents, glimpsed something even deeper at work: “There were too many Huxleys in that situation ... involving the shadows of our parents and the way we react to them.” This cryptic observation hinted at buried family secrets — perhaps even his mother Juliette's initial attraction to Aldous before she settled for Julian. The LSD had not just revealed the younger generation's desires; it had somehow excavated and reenacted the hidden dynamics of their parents' lives. In the same letter, Francis attempted to reassure his parents who were deeply concerned about his affair with Ellen: “No one is likely to explode or throw himself under a car, or do anything foolish.”

Each participant of that day in November 1956 forged their own path. Ellen finally broke free of domestic constraints, becoming a documentary filmmaker and co-directing the cult classic “Grey Gardens.” Matthew remarried in 1963, with Aldous attending the wedding just months before his death from cancer. He also decided to write a book about a different Amazonian tribe — “Farewell to Eden,” published in 1965 — a move that seemed, perhaps unconsciously, like a bid to rival his cousin’s intellectual terrain. Francis, meanwhile, continued his anthropological wanderings, carrying whatever insights or regrets he gained from that night into his studies of other cultures' sacred rituals. Unlike Matthew, Francis continued to take psychedelics throughout his life and became an advocate for the collective rights of Indigenous people.

Yet the questions raised by that evening in Connecticut still resonate. Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley would later privately debate LSD's power as an emotional and sexual catalyst.

“We've stirred up enough trouble suggesting that drugs can stimulate aesthetic and religious experiences," Aldous cautioned. “I strongly urge you not to let the sexual cat out of the bag.”

It may be too late for that. In the present day, Women's Health asks “Could MDMA save your marriage?” while Psychology Today suggests that “[p]sychedelics may foster peace among couples, families, coworkers and nations.”

Mind-altering drugs and marital weirdness have long gone hand-in-hand. Years later, in 1967, John Lennon would dose his wife Cynthia with LSD at a party at Brian Epstein's house — leading to a nightmarish experience in which she saw her husband transform into a demonic figure, fracturing their already strained marriage.

Earlier this year, the New York Times covered the fractures that emerged in the close-knit psychedelic scene over a sexual abuse scandal that dogged an inquiry into MDMA as therapy for PTSD. A husband-wife therapy team in Canada spooned and cuddled a participant during her MDMA session. While MDMA is different to the “classic” psychedelic drugs like LSD, it can relax boundaries in the same unsettling way. After the trial ended, client and therapist began a sexual relationship.

In 2021, a student in the California Institute of Integral Studies' psychedelic therapist training program, Will Hall, came forward about sexual abuse allegedly committed by two celebrated healers, Francoise Bourzat and Aharon Grossbard.

In the 1980s, Dr. Richard Ingrasci positioned himself as a trusted guide into altered states. He built a sterling reputation through research publications and mainstream media appearances, even testifying to Congress in 1985 that MDMA had a “low potential for abuse” and should remain legal. But in 1989, his photo appeared on the Boston Globe's front page with a chilling headline: “Therapist accused of sex abuse of clients.” According to Psymposia, multiple troubling abuse allegations were leveled — including by one woman who attempted suicide in the aftermath — but charges were dropped after Ingrasci surrendered his medical license.

But perhaps psychiatrist Sidney Cohen came closest to understanding what had really happened to the Huxleys when he wrote that “LSD does nothing specific ... it springs the latch of disinhibition.” The drug hadn't created these currents; it had simply made them impossible to ignore. It changed forever how three generations of Britain's most celebrated intellectual family would understand themselves and each other.