The legendary film critic Roger Ebert called film “the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts”. Cinema offers us complete immersion in another reality, taking us on an almost out-of-body experience into someone else’s life and experience.

But as one oft-filmed character says, with great power comes great responsibility, and the very best films use that power to help us. They might offer an escape from our own lives, the catharsis of a huge hit of action, horror or adventure that makes our own everyday problems seem small. They might reflect our lives on a more human scale, giving us the sense that we are not alone in our concerns and examining our emotion to find the common threads that bind us. Or they could play out possibilities for our own lives, letting us see the consequences of an affair or murder plot unwind before our eyes so we don’t have to flirt with disaster in reality.

Film is well over a century old now, and with competition from TV and games it may never again reach the audience numbers that it did in its 1930s golden age. But it can still offer an emotional hit like nothing else when there are hundreds of us together, in the dark, losing ourselves in a moving picture – and here are 35 of the best ever to sweep us off our feet.

Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

With this update and upgrade of the 1930s serial adventure, Steven Spielberg turns what could have been pastiche into a practically perfect film. Harrison Ford’s daring archaeologist is almost always out of his depth but has impeccable underdog charm, and Douglas Slocombe’s casually stunning cinematography is matched by one of John Williams’s finest scores. Indiana Jones is ultimately irrelevant to the entire plot, interestingly, but his indefatigable effort to do the right thing still inspires. HO

Spirited Away (2001)

Japanese animation legend Hayao Miyazaki’s films delight kids with their bright colours, imaginative characters and plucky heroines (usually). But there’s meat to their bones for adults to digest, especially in this towering fantasy epic. As young Chihiro takes a job in a mysterious bathhouse peopled by spirits in order to save her parents, viewers can explore everything from deeply rooted interpretations of traditional Japanese myths to Miyazaki’s fascination with Western filmmaking and the Second World War. And visually it’s unparalleled. HO

The Conversation (1974)

Francis Ford Coppola slipped this paranoid masterpiece in between the first two Godfathers, though it was left to his wizardly editor Walter Murch to resolve the plot in post-production. Gene Hackman, never better, plays Harry Caul, a loner surveillance expert called upon to pry into a situation he doesn't fully understand, and winding up dangerously complicit in murderous malfeasance. No other film managed to foreshadow Watergate quite so uncannily. PS

Avengers (2012)

Yes, but hear us out: Avengers is a grand experimental film. Marvel risked four popular franchises on this superhero throw of the dice, something never attempted in cinema history. They won, and made the fizzing chemistry of the unlikely gang who must save us from aliens look easy. But the failure of every Marvel imitator since makes clear how impressive this billion-dollar gamble really was, and how difficult it is to tell character-driven stories in blockbuster cinema on this scale. And as a bonus, it has a Hulk. HO

The Shining (1980)

Stanley Kubrick’s creep-show classic is remembered for the indelible images of that violent finale chase, but its reputation and influence stem from the slow-winding tension that precedes it. Jack Nicholson is the struggling writer whose sanity frays over a winter season at an isolated and haunted hotel; Shelley Duvall plays his increasingly desperate wife. Touching on questions of domestic violence as well as delivering a ghost story for the ages, this will get under your skin and stay there. HO

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

One of those remakes that justifies remakes, Philip Kaufman’s beautifully skilful spin on the McCarthy-era alien-clone thriller translates it wickedly to the psychobabble age of the 1970s, with a bit of post-Watergate panic thrown in. Donald Sutherland’s lugubrious health inspector is a nicely grumpy enemy of the pod people, and the hysteria ratchets up masterfully. PS

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

Wes Anderson’s meticulously mannered and beautifully composed films are not to all tastes, but when combined with a cast of this calibre and a more-than-usually heartfelt script, they are capable of magic. Gene Hackman plays the disgraced patriarch of a family of geniuses, making one last attempt at redemption. With a who’s who of Hollywood in support, it’s a story that is as bizarre, hilarious and moving as family life itself. HO

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

David Lean’s First World War epic about TE Lawrence remains a filmmaking milestone, the movie that Steven Spielberg rewatches before starting each new film. Its genius is to combine huge scale battles – notably the attack on Aqaba – with psychological insight into the toll that the war took on Lawrence’s mind. The white-led casting of Arab characters is appalling to modern eyes, but with its daring, dazzling filmmaking it remains one to watch despite that. HO

Bicycle Thieves (1948)

A devastating portrait of the poverty trap, Vittorio De Sica’s neo-realist masterpiece remains all too relevant. Antonio (Lamberto Maggiorani) is offered a desperately-needed job – but it requires a bicycle, and when his is stolen, he and his son resort to desperate measures to get it back. Shot with non-professional actors who lived in circumstances close to that of their characters, this is a study in compassion and empathy. HO

Farewell My Concubine (1993)

Spanning five decades of Chinese history, this sprawling epic follows two stars of the Peking Opera from harsh childhood training through the perils of the Second World War, the communist takeover and the Cultural Revolution. Director Chen Keige drew on his own experience of the Cultural Revolution to shape this groundbreaking, tormented romance both between Zhang Fengyi’s Ziaolou and Leslie Cheung’s Dieyi, and between Ziaolou and his former prostitute wife Juxian (Gong Li). HO

Tokyo Story (1953)

Pauline Kael thought that the basic appeal of movies was the “kiss kiss bang bang” of action and romance, but Yasujirō Ozu demonstrates that film is capable of much more in this quiet family drama. It’s a simple story about two elderly parents visiting their adult children, only to find that the younger generation is busy with other things. But it’s also a meditation on the passing of time, and on grief, and on the constant push towards the new that will break your heart every time you watch it. HO

Read more: Netflix secret codes: How to access hidden films and TV shows on the streaming service

Double Indemnity (1944)

If we have learned anything from film noir, it is that murder pacts never work out well for both parties. That’s certainly the lesson when Fred MacMurray’s infatuated salesman offers life insurance to Barbara Stanwyck’s femme fatale Phyllis against the will of her unloved husband. The scheme gives way to a riveting stew of suspicion and paranoia, with Stanwyck’s ruthless determination warping MacMurray’s out of all recognition as director Billy Wilder tightens the screws. HO

Days of Heaven (1978)

Terrence Malick’s second, and for many, greatest film is a mesmerising, gorgeous love triangle set in the Texas Panhandle in 1916, loosely based on an Old Testament parable. Richard Gere and Brooke Adams are the lovers who pose as brother and sister to fool a rich, dying farmer (Sam Shepard). Nestor Almendros’s astounding magic-hour photography rightly won an Oscar, and Linda Manz supplies heartbreaking, plainspoken narration as Gere’s younger sister. PS

Citizen Kane (1941)

The problem with calling something “the greatest film ever made” is that it begins to sound like homework. Forget that: beyond all the technical dazzle and ground-breaking filmmaking Orson Welles’s masterpiece has red blood in its veins and a huge beating heart. What’s more, its portrait of a thrusting, occasionally demagogic tycoon and the hollowness at the heart of his success remains as relevant as it ever was, and the suggestion that America might be susceptible to media manipulation is all too believable. HO

Les Enfants du Paradis (1945)

Marcel Carné's immortal saga about a 19th-century Parisian theatre company – often called the French Gone with the Wind – has a swooning romanticism but majors in heartbreak, too. Among this ensemble, brilliantly played by some of the best Gallic actors of their day, hopes rise and are shattered, and jealousy mounts among all the acolytes of a courtesan called Garance. It looks back to mime and stagecraft as essential components in the prehistory of cinema, while also being great cinema. PS

Rear Window (1954)

Whether you see it as Alfred Hitchcock’s celebration of voyeurism or simply one of the most nail-biting thrillers ever made, it’s a superb example of the Master of Suspense at work. James Stewart’s photographer, laid up with a broken leg, becomes obsessed with the lives of his neighbours and suspects one of murder. The unusually vulnerable hero – as in Vertigo – increases the stakes and ensures that simple brawn won’t save the day, while Hitchcock ratchets up the tension unbearably by putting Grace Kelly’s plucky girlfriend in the lion’s mouth. HO

It Happened One Night (1934)

Claudette Colbert’s eloping heiress and Clark Gable’s hack on his uppers warily team up on a Greyhound bus, only to aggravatingly fall for each other. Frank Capra’s evergreen romcom all but invented the love-hate formula that’s one model for silver screen chemistry, hoicking up Colbert’s skirt to flash a leg when they need to hitch-hike, and dismantling Gable’s smarmy defences. The biggest hit of its day for a reason, it was also the first ever film to win the big five at the Oscars. PS

Hoop Dreams (1994)

The trials of young black basketball hopefuls in Chicago tell us volumes, from their upbringing to all-or-nothing career rimshots, about the opportunities otherwise denied them. For these portraits of inner-city poverty, gliding between frustration and triumph, Steve James’s epic of ghetto realities has been influential on every sports doc that has come in its wake. The Academy’s documentary branch will never quite live down failing to nominate it. PS

The Apartment (1960)

This blistering Billy Wilder and IAL Diamond script is a demonstration of just how dark a love story can get without tipping entirely into bitterness, a standing rebuke to every lazy, schmaltzy comedy going. While the entire cast is stellar and Shirley MacLaine was never better, it’s worth ignoring them all and just watching Jack Lemmon’s meek office worker CC Baxter. Every gesture and glance is flawless; he carries entire scenes without a word. HO

Paris, Texas (1984)

In Wim Wenders's Palme d'Or-winning trek through America's byways, Harry Dean Stanton plays a wreck of a man who's gone missing, found wandering silently through the Texan wilderness. He travels hundreds of miles to reconcile with his ex (Nastassja Kinski), whom he finds, oblivious to who he is, on the other side of a Houston peepshow window. Culminating unforgettably with this long-take tête-a-tête, it's a shattering quest for redemption, eerily scored by Ry Cooder. PS

Before Midnight (2013)

Céline (Julie Delpy) and Jesse (Ethan Hawke) have settled down since the two earlier films in Richard Linklater’s essential triptych, Before Sunrise (1995) and Before Sunset (2004), but the problems in their lives – self-inflicted by now – only keep proliferating. Trenchantly pushing them into full-on battle-of-the-sexes territory, the film squares them off for a bitterly adult dissection of a long-term relationship, asking stark questions about love, compromise and lasting the course. PS

Le Mépris (1963)

Other Jean-Luc Godard films are punchier, ruder, more experimental. But this is his most lavish, measured, and sad: an elegiac fantasy of filmmaking, as a loose adaptation of The Odyssey grinds to a halt on Capri, with Jack Palance as the brash American producer trying to sell art by the yard. Meanwhile, the screenwriter (Michel Piccoli) and his beautiful, bored wife (Brigitte Bardot) tussle and reconcile in an incessant, pained ballet. PS

Casablanca (1942)

Some films strain under the weight of greatness; Casablanca’s quality bubbles through. Against the backdrop of the Second World War, two former lovers reunite though everything in the world is pulling them apart. Bogart’s Rick hides a huge heart under a thin veneer of cynicism; opposite him, Ingrid Bergman’s luminous Ilsa could melt an iceberg. Packed with quotable lines and brimming over with impeccable cool, here we are, still lookin’ at you, kid. HO

A Trip to the Moon (1902)

Georges Méliès pioneered many of the visual and special effects techniques that have formed the backbone of fantastical filmmaking ever since, and he pushed them all to their limits in this turn-of-the-century tale of a rocket trip to the moon to meet the strange creatures who live upon it. Witty touches and a real sense of story mean that this is still entertaining more than a century later, and if the effects are less awe-inspiring now, they’re still beautifully designed and executed. HO

His Girl Friday (1940)

A screwball comedy of substance, Howard Hawks’s remake of The Front Page is an objectively odd mix of high stakes and high comedy. Yet it works because the machine-gun dialogue is so quick that there’s never a moment to question what’s happening (the great screenwriter Ben Hecht, who co-wrote the original Broadway play, worked on it uncredited). Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell, as the warring editor and star reporter trying to work together long enough to land the story of the year, remain the standard by which all on-screen chemistry should be judged. HO

Blow Out (1981)

John Travolta’s Z-movie sound man, out recording one night, accidentally tapes what turns out to be a political assassination. Brian De Palma hit peak ingenuity and gut-punch profundity with this stunning conspiracy thriller, mounted with a showman’s élan but also harrowing emotional voltage from its star. It’s one of the most delirious thrillers of the 1980s, with a bitterly ironic pay-off that’s played for keeps. PS

City of God (2002)

There’s a deep contradiction at the heart of this acid-bright portrait of the violence in Rio’s favelas. On one hand these child hustlers and teen gangsters have an intense lust for life, an exuberance displayed in dance and play and love; on the other, they value life cheaply and take it without a qualm. Director Fernando Meirelles and co-director Kátia Lund cast a talented band of local kids to give it authenticity and then punctuated their story with Scorsese-esque violence that still shocks. HO

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

The diverging romantic fortunes of Hannah (Mia Farrow), Lee (Barbara Hershey) and Holly (Dianne Wiest, who won an Oscar, as did Michael Caine) provide an ideal structure for Woody Allen to check in on a midway state of adulthood, when there’s already a sense of disappointment about squandered promise, but still much to play for. It hits the miraculous sweet spot between all Allen’s modes and tones. PS

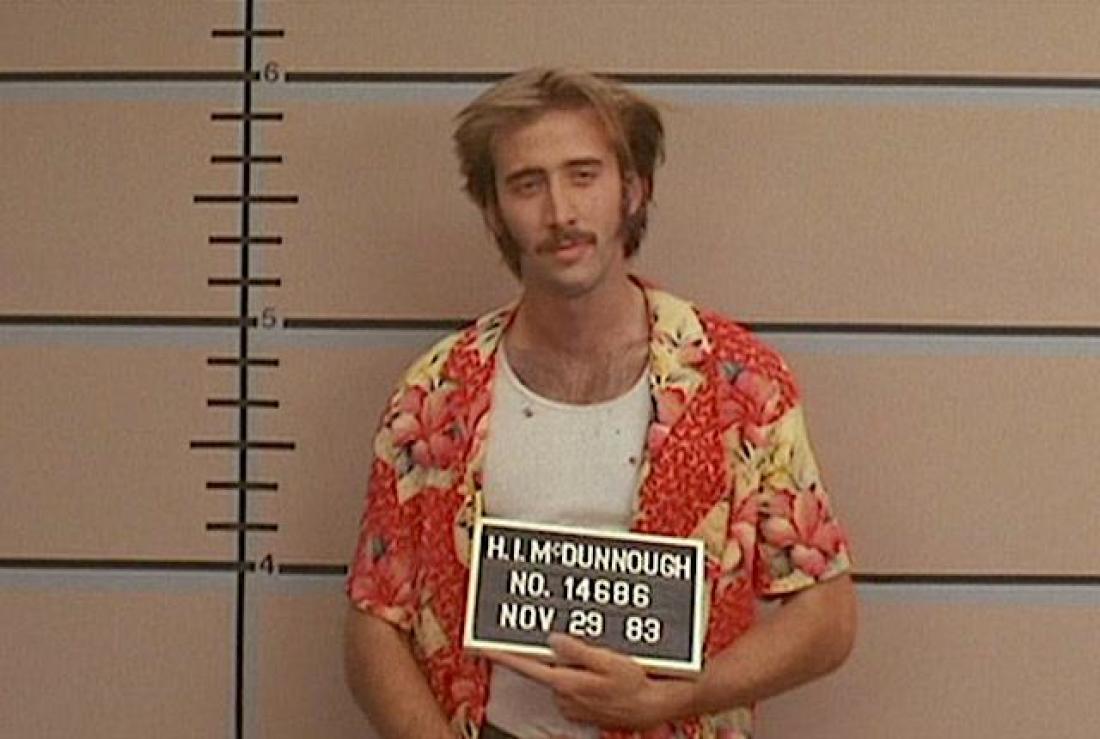

Raising Arizona (1987)

The Coen Brothers had already established a ghoulish signature style with Blood Simple, but here they showed us how funny they could be, in a zig-zagging kidnap farce which manages the difficult feat of being both zany and adorable. Nicolas Cage and Holly Hunter are the unlikely couple whose abduction of a spare newborn quintuplet, Nathan Jr, causes all hell to break loose. PS

Caché (2005)

This looks and acts like a thriller, but in reality Michael Haneke’s exploration of colonialism, guilt, paranoia and privacy cares more about subtext than about scares or mystery. A well-to-do Parisian family are tormented by the arrival of surveillance tapes of their lives, but it’s not clear who could be sending them or why, leading patriarch Georges (Daniel Auteuil, never better) to confront his own past sins. As a subversion of genre and viewer expectation, there are few to match it. HO

The General (1926)

Orson Welles suggested that Buster Keaton’s silent Civil War comedy might be the greatest film ever made, and who are we to argue? Keaton’s Johnny Gray is a key figure on the railroads of the Confederacy, but he and his engine, The General, must go above and beyond to defeat a Union spy. Ignore the dodgy politics and focus on the sublime physical comedy of Keaton’s beautifully composed routines. You’ll come out wondering if movies even need sound. HO

The Babadook(2014)

The Babadook is a black, hunched pop-up book monster who raps on your door three times before paying a visit. And you can’t get rid of him. Widowed mum Amelia (brilliant Essie Davis) can’t remember reading his book to her emotionally disturbed misfit of a son (Noah Wiseman) before. Jennifer Kent’s thoughtful Australian chamber shocker, a feast of inventive design, claws its way into you and leaves scratch marks. PS

When Harry Met Sally (1989)

Is it impossible for men and women to be purely platonic? It is according to Harry, in this beautiful, brainy comedy about two neurotic New Yorkers who become friends. Directed by Rob Reiner and written by wonderful Nora Ephon, it’s a paean of sorts to Woody Allen’s early films, with razor-sharp observations about sex and dating (“I’ll have what she’s having”). It’s still the pinnacle of both Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan’s careers. PS

Inside Out (2015)

Toy Story revolutionised animation; Up and Wall-E vie for the best opening of any film this century, but for sheer audacity Pete Docter’s head-trip must prevail. As a little girl struggles to adapt following a family move across country, her emotions go on a madcap adventure through the mind itself. What’s dazzling here is that two completely separate films unfold at once. Kids watch brightly coloured sprites on a quest; adults watch a psychologically dense depiction of how we think and feel. It’s wonderful. HO

True Romance (1993)

Disinterred from a script Tarantino wrote in the mid-Eighties called The Open Road – the same screenplay that also spawned Natural Born Killers – Tony Scott’s True Romance is a dirty, hyper-violent twist on a damsel-in-distress fairytale, with a plinky-plonky score indebted to the fugitive classic Badlands. Christian Slater and Patricia Arquette are the lovers on the lam, chased by Christopher Walken’s suave mafioso. Bombastic, brash – and totally brilliant. PS