The authorities overseeing the rescue of 12 boys and their football coach from a cave in northern Thailand have a difficult decision to make.

Option A is to pump enough water out of the Tham Luang cave complex so that the children can simply walk out, more or less the way they came in before they became trapped by a surge of floodwaters 12 days ago.

A more unlikely option, but one which is being explored, is to try and find - or even drill - other routes into the chamber where the boys are trapped. Without detailed surveys of the cave network, though, experts say it would be like searching for a needle in a haystack.

The third, arguably safest route would be to wait it out until the rains subside naturally. Given Thailand’s monsoon season ends around October, it would mean waiting up to four months in a dark cave and with no guarantees that the chamber itself won’t fill up with water too.

That means the officials in Chiang Rai are currently preparing most urgently for option D: teaching the boys, some of whom cannot swim and none of whom have ever used scuba equipment before, to dive out of the flooded cave themselves.

What are the risks?

“It takes six hours to get to where the children are and five hours to come back,” said Major General Chalongchai Chaiyakum, deputy commander of the Third Army Region.

And that’s just for the experienced navy SEAL divers. The route from the chamber to the surface will see the boys contend with debris clogging some of the passageways, high water levels with strong currents to fight against, and almost zero visibility in the dark, muddy water.

Thomas Hester, detective superintendent with the Australian Federal Police Specialist Response Group, said there were "heavily flooded areas" inside the cave complex.

"It's very difficult to see, very difficult to move inside that flooding system," said Hester.

Rockfalls are also a threat, but its one that is expected only to rise if the team waits to move until new floodwaters hit the area.

The route

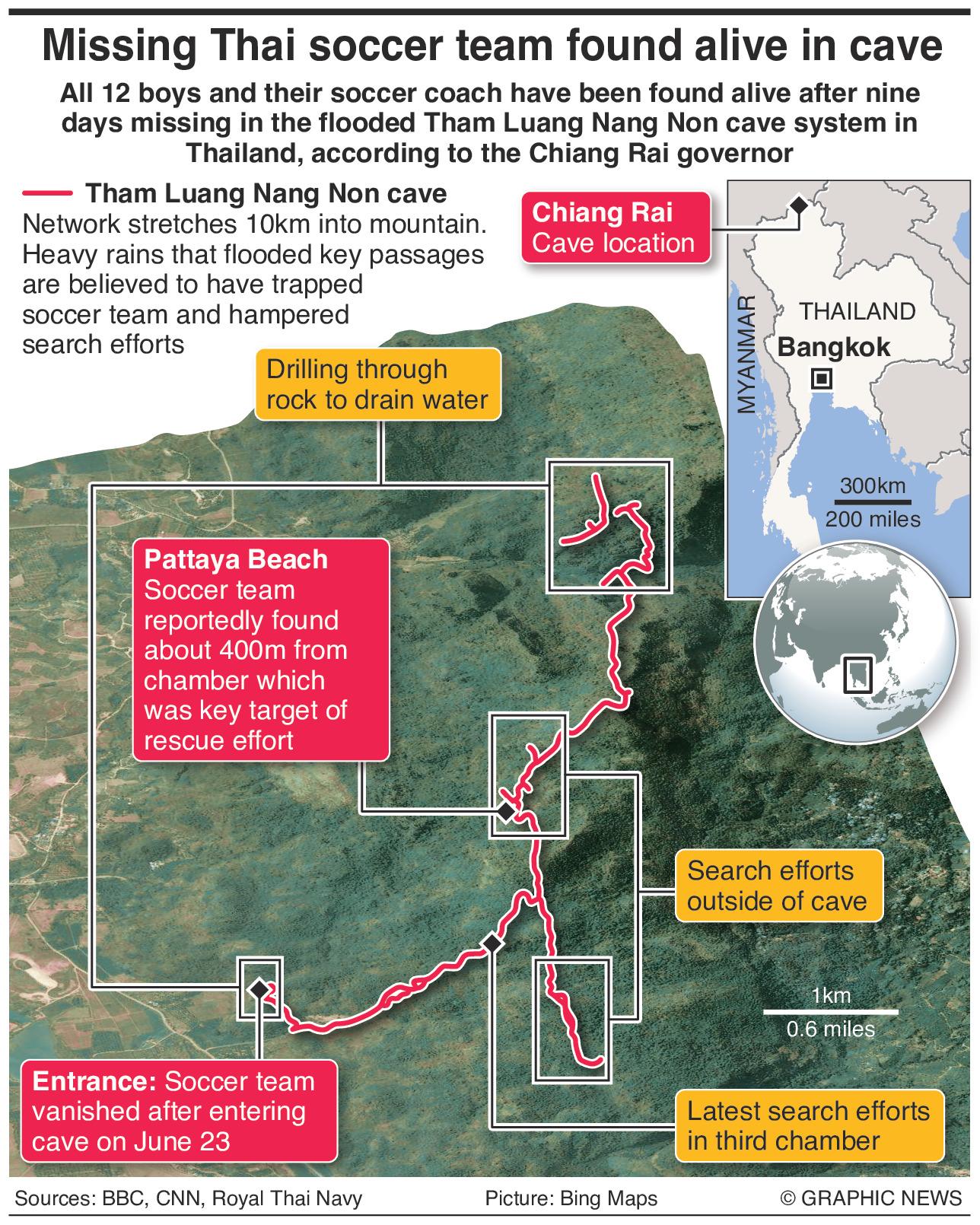

The boys were found on an shelf above the floodwater about 400 metres from Pattaya Beach, a large, elevated point inside the cave complex.

After Pattaya Beach, the boys will be aiming for a T-junction in the network, but this stretch has been described as a “crisis” point in the Thai navy’s maps of the route. It is an area where rescuers say the cave dips down and debris, mud and water pools, requiring constant clearing.

"From the T-junction to Pattaya Beach (there) is a slope and a passage about 15 metres long, a very narrow passage. Small people can push through but not large people. You have to go in one at a time. Those who are using an oxygen tank have to remove it push it forward.... After this point you come to a dry area," Chalermphon Hongyon, president of the Water Rescue Club Region 7, told reporters.

From the T-junction to the entrance of the cave water levels are currently "manageable", said Chiang Rai Governor Chiang Rai Governor Narongsak Osottanakorn.

How are they preparing?

Chiang Rai’s provincial governor, Narongsak Osatanakorn, said on Thursday that he had ordered navy SEALs to prepare to extract the boys before a new bout of heavy rain, forecast to hit the area on Saturday.

Several days of dry weather have allowed authorities to drain more than 130 million litres of water from the cave system, but the drop in levels has not been enough to avoid the need for diving altogether. That progress is likely to be lost once the new rains arrive, making any diving rescue attempt almost impossible.

As a result, Mr Narongsak said they may “take that chance” to get the boys out before they are completely prepared. He said the 13 may not be extracted at the same time, depending on their condition. They've practiced wearing diving masks and breathing, in preparation for the possibility they may have to dive.

"This (Thursday) morning, I have asked for 13 sets of (diving) equipment to be prepared and checked the equipment lists and place them inside (the cave) in case we have to bring them out in this condition with less than 100 per cent readiness," he said.

Divers have also been placing hundreds of oxygen tanks to refill from along the route, as well as laying down lights and guidelines to minimise the risk of the boys either panicking or getting lost.

Will they dive alone?

The idea of draining the caves is to get some headroom so the boys would not be reliant on scuba apparatus for a long stretch and could keep their heads above water.

When they do have to go under, they will be accompanied by one or two experienced divers each, and tethered to their minders. Some of the children may be considered strong or capable enough to carry their own oxygen tanks, but most won’t have to worry about that.

Martin Grass, Chairman of the Cave Diving Group, told the BBC he expects the boys to be given full-face masks, light wetsuits and diving flippers, and to be under water for stretches of 10 to 15 minutes at a time depending on the level of flooding.

"It could be a bonus that the boys are young. When you're young, you feel invincible and they'd see it as a bit of an adventure," he said.

How have they coped being trapped for 12 days?

Practically speaking, the boys were able to survive on some snacks and water they brought with them for their trip to the caves, rationed out over the nine days before they were found, as well as rain water dripping from the chamber’s ceiling.

When they were found, the boys were seen in videos to be skinny but in good condition. One rescue diver said the coach, 25-year-old Ekapol Chanthawong, was actually the weakest of the group because he refused to take any food from the boys.

But what is more remarkable for some rescuers is the strong mental state the boys appear to be in. Some are attributing that to the guidance of Mr Ekapol, who before becoming coach to the youth football team spent a decade as a saffron-robed Buddhist monk.

(AFP/Getty Images)

"He could meditate up to an hour," his aunt, Tham Chanthawong, told the Reuters news agency. "It has definitely helped him and probably helps the boys to stay calm."

Aisha Wiboonrungrueng, whose 11-year-old son Chanin is trapped in the cave, has no doubt that Mr Ekapol's calm personality has influenced the boys' state of mind.

"Look at how calm they were sitting there waiting. No one was crying or anything. It was astonishing," she said, referring a video that captured the moment the boys were found.

Experts agreed that the group will continue to face challenges even after they make it out of the cave. Thailand's Department of Mental Health said hospitals are making preparations to care for the boys' and will monitor them until their mental health is fully regained. They are also working with the families to prepare for how to interact with the boys once they get out, such as not digging for details about what they endured.

"Their re-entry into the world outside the cave will predictably be one of massive attention from family, friends and the media," said Paul Auerbach, of the Department of Emergency Medicine at Stanford University's medical school, noting it could be overwhelming. "The world soon loses interest and moves on to the next story, so it is extremely important that these survivors not be forgotten and be closely monitored so that they can receive the best possible support."