The Democratic Republic of Congo gears up for elections on Wednesday that could consolidate its democracy or unleash fresh violence as political tensions threaten to boil over.

Some 44 million registered voters are set to cast ballots in the vast central African nation of about 100 million people on December 20 in presidential, parliamentary, provincial and municipal polls.

About 100,000 people are standing in the four votes, with President Felix Tshisekedi seeking another term after winning a disputed election in 2018.

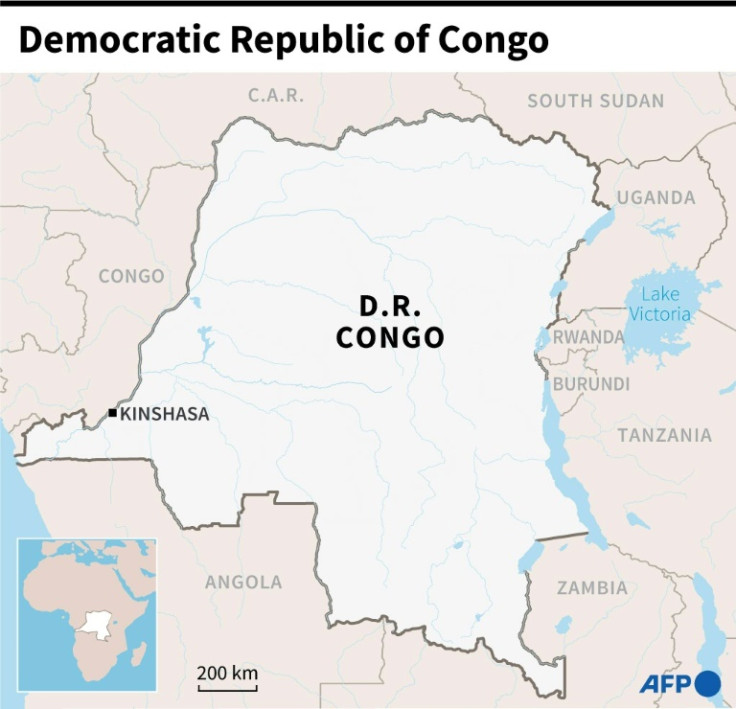

The sheer size of the DRC, which is roughly the size of continental western Europe, means staging elections is a logistical nightmare.

The country is also one of the world's poorest and has little high-quality infrastructure, with the CENI electoral commission still struggling to distribute voting material to more than 175,000 polling booths.

Political scientist Gaucher Kizito Mbusa told AFP that voting should go smoothly in the more densely populated zones but would be difficult in rural areas due to insecurity and poor roads.

The UN Security Council on Friday approved a government request that the outgoing peacekeeping mission in the country, MONUSCO, provide logistical support beyond the three violence-wracked eastern provinces where it is deployed.

A diplomat told AFP that not all voting stations will open on December 20 due to a lack of equipment, saying some may operate a day or two after or even later.

In a report published on Saturday, Human Rights Watch (HRW) warned of electoral violence that "risks compromising the holding of the vote".

The NGO says it has documented clashes between supporters of rival parties since early October that have led to "assaults, sexual violence and at least one death".

Given the DRC's turbulent political history, the fiercely contested 2018 elections passed off calmly and marked the country's first peaceful handover of power.

But the political scientist said "intolerance" had crept into the debate, while the diplomat said "hate speech" was prevailing over ideas and programmes.

The announcement of the results, expected several days after polls close, may be when the danger is greatest.

Fraud remains a key concern and all the major opposition presidential candidates have urged vigilance.

The opposition has long accused the government of stacking the electoral commission and the Constitutional Court, the final arbiter of electoral disputes.

Analysts say unrest will be muted if the official results match with those of observers, notably from various churches, but not if they diverge.

Raging conflict in the east, plagued by armed groups for more than three decades, has also poisoned the campaign trail.

The M23 rebel group has advanced over swathes of North Kivu province since its re-emergence from dormancy in late 2021.

HRW said more than 1.5 million Congolese will be unable to vote in zones affected by the conflict and that millions more internally displaced people will face the same challenge.

Three days before the vote, 19 candidates were still in the running for president.

The major opposition figures standing include Moise Katumbi, a wealthy magnate and former provincial governor who has won the backing of four former contenders.

The other main opposition hopefuls are Martin Fayulu, an ex-oil executive who says he was the true winner of the 2018 election, and Denis Mukwege, a gynaecologist who won the Nobel Peace Prize for his work with rape victims.

Amid a lack of credible polling, some observers believe Tshisekedi and Katumbi are the likely frontrunners judging by their resources and the size of their following at campaign events.

But with the opposition split, Tshisekedi is viewed as having the best chance of winning.

Rallies will continue until Monday when campaigning officially ends.