Way back in September 2015, the controversial engineer, entrepreneur and Silicon Valley magnate Anthony Levandowski set out to establish a new religion. He called it the Way of the Future – or WOTF.

According to documents filed with the state of California at the time, the aim of WOTF was to “develop and promote the realisation of a Godhead based on Artificial Intelligence”.

Levandowski’s idea was that, even though it had not yet been born, we should all begin worshipping a technological god in advance. For, on the inevitable day of its arrival, that might be the only way to avoid its horrible wrath.

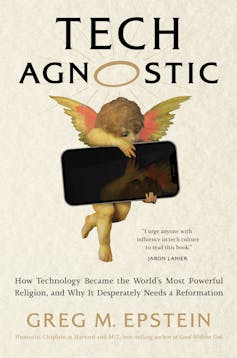

Review: Tech Agnostic: How Technology Became the World’s Most Powerful Religion, and Why It Desperately Needs a Reformation – Greg M. Epstein (MIT Press)

Almost a decade later, technology has yet to reach the status of a god, either vengeful or benevolent. But the use of religious language to describe technology has become widespread.

Those working on AI, for example, tell us that its powers will soon become “magical”. Modern day prophets like Ray Kurtzweil and his many followers insist we are on the verge of a “singularity”, in which technology will allow us to surpass all previous limitations on human existence, including death.

Figures like Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, can be heard saying things like “I don’t pray for God to be on my side, I pray to be on God’s side”, and “working on these models definitely feels like being on the side of the angels”.

Even the billionaire media mogul Oprah Winfrey has assured us, in a recent television special, that contemporary intelligent technology is nothing less than “miraculous”.

The tech religion

This surfeit of religious rhetoric could be chalked up to the ostentatious hyperbole that characterises Silicon Valley capitalism. Indeed, draping commodities in the patina of divinity is hardly a new marketing strategy.

But according to Greg Epstein, the secular ethicist and former humanist chaplain at Harvard and MIT, we find ourselves talking about modern technology in religious terms because modern technology (or what he calls “tech”) has effectively become a religion. And “not only a religion”. Epstein declares tech “the dominant religion of our time”.

No other force on the planet attracts as much praise. No other power demands as much devotion. Nothing else has such a firm grip on the rituals and practices of our daily lives.

At first glance, the idea that tech has become a new religion seems to have some explanatory power. It is not just that things like smartphones, algorithms, apps and social media form integral parts of our economic worlds. Nor is it simply that they have infiltrated every aspect of ordinary experience, such that it would be almost impossible to function without them.

It is that the cultures that have grown up around these tools have come to dominate the way we understand ourselves, our collective existence, and even our place in the universe.

As Epstein puts it, “tech provides contemporary western lives, so polarised and divided in countless ways, with a common principle, a common story by which we tell ourselves who we are”. What’s more, tech promulgates “moral and ethical messages, not as mere secondary features, but as integral to its overall value(s) proposition”.

Thus corporations like Google or Alphabet and individuals like Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg are not content with accumulating mindboggling wealth. They take it upon themselves to issue commands like “don’t be evil”, “do the right thing” and “make history”. They enthusiastically proclaim the good news of a “connected future” that will “give everyone a voice” and “transform society.”

As a result, Epstein reasons:

Tech is not an ordinary “industry”, where profit and loss statements, product sold, or efficiency gained can tell its story. The story of tech’s commercial success […] is a story about how human beings understand ourselves in the world. It is a story of where we get a sense that our existence is meaningful, that our day-to-day lives have purpose.

Elites and extras

Amid a considerable amount of detail, Epstein’s analysis of this new religion has two basic components.

On the one hand, he suggests that, as it currently stands, the tech religion serves to divide humanity into a small number of chosen people and the vast majority of the damned. It portends that elected souls will soon be uploaded into a paradise of disembodied immortality, while the rest will become slaves to the machines or condemned to oblivion.

On the other hand, as his title indicates, Epstein is a tech agnostic – not a tech atheist. His call is for the “reformation” of the tech religion, not its abolition. He thus recommends that we place our faith in a host of what he calls “apostates and heretics”: those who are developing critiques of the tech religion and offering credible alternatives.

On this side of the ledger, Epstein places proponents of “responsible” and “ethical tech”. He hopes a loosely affiliated cluster of such figures will somehow come to form a “congregation” that will confront the established order, take charge of the tech narrative, and bend it in the direction of human justice and equality.

Epstein’s conceit of tech as a religion has heuristic value, but somewhere along the way it becomes a little forced. He starts to grasp for any connection he can possibly draw between the two fields. His central argument gets lost. In its place, we have a string of possible affinities, some more credible than others.

Moreover, despite Epstein’s repeated efforts to suggest otherwise, it is not at all true to say that contemporary Silicon Valley capitalism is the first form of capitalism to characterise itself as ethical or spiritual, rather than a crassly commercial endeavour.

From the doux commerce arguments of the 18th century to the founding fathers of neoliberalism, capitalism has always presented itself as an essentially moral project designed to transform unruly human passions into rational human interests. What is Adam Smith’s famous “invisible hand” of the market if not a secularised version of Providence?

One of the most striking features of Tech Agnostic, much of which consists of interviews with industry and academic elites, is Epstein’s incredible access to these figures – something undoubtedly made possible by his association with elite institutions like Harvard and MIT.

Yet about halfway through the book, Epstein stumbles on the following formulation: “For every tech executive or highly educated westerner reaping the benefits of AI and social media connections, how many traumatised content moderators are there in Manila […] lithium miners in the Congo […] Chinese factory workers?”

Tech, he proposes a little later, “needs fewer sweeping and certain narratives and many more close up character studies of the actors it currently considers extras. Can those who reap the benefits from tech’s many successes take time to better understand the reality of those suffering here and now?”

These are excellent questions that Epstein, for all his insight, could have very effectively posed to himself.

Charles Barbour does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.