Scientists have discovered a new species of rosy-colored deep-sea worm 30 miles (50 kilometers) off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica.

The worm, named Pectinereis strickrotti, is a type of ragworm, or Nereididae. It was first spotted by researchers in 2009, as they explored a methane seep found at a depth of 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) while onboard a deep-sea submersible called Alvin.

In 2019, the team returned to the same area and spotted six more of the critters and were able to take images, videos and samples needed to formally classify P. strickrotti as a new species. The team described their findings in a paper published March 6 in the journal PLOS One.

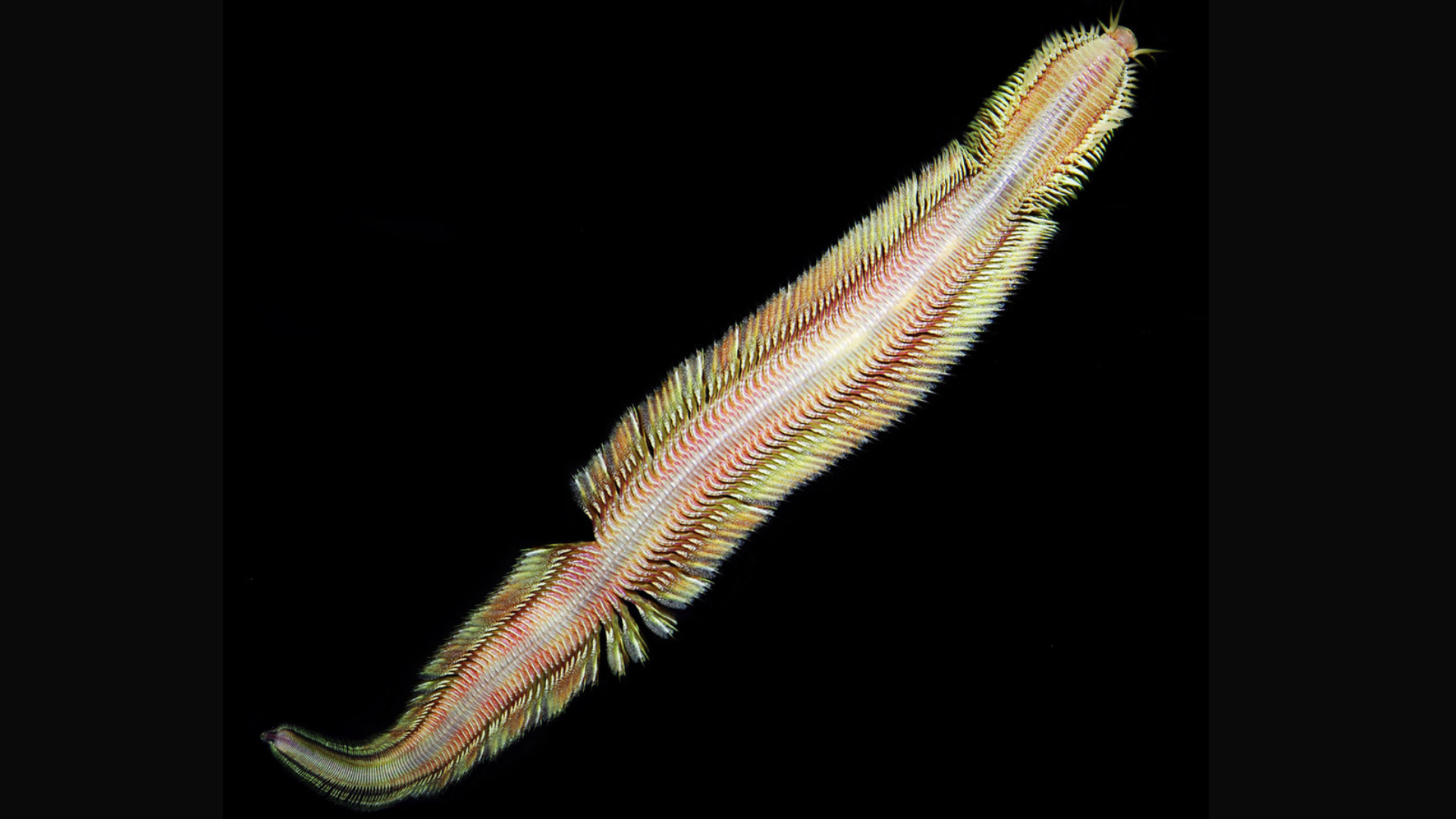

P. strickrotti has a segmented, elongated body which is around 4 inches (10 centimeters) long. Like other ragworms, it looks like a cross between a centipede and an earthworm. It also lives in marine environments, as many ragworms do, although P. strickrotti lives in deep sea rather than shallower waters.

On each side of its body, it has a row of feather-like outgrowths called parapodia, tipped with gills that allow it to absorb oxygen from water. The worms also have a hidden collection of "pincer-shaped" jaws that can be thrust out when they need to catch prey to eat, although scientists don't yet know what their diet consists of, according to a statement.

Related: Watch hypnotizing footage of mysterious deep-sea worm dancing in the twilight zone

P. strickrotti looks like a snake as it swims, making many curves and turns as it glides through the water, the scientists observed. "The way this thing moved was so graceful, I thought it looked like a living magic carpet," Bruce Strickrott, the lead pilot for Alvin at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts and whom the species is named after, said in the statement.

Under the lights of the submersible Alvin, the worms also looked "rosy" which is likely due to the color of their blood, the team said in the statement. Unlike other ragworms, P. strickrotti are blind as they live in total darkness at such great depths.

So far, the team have found around 450 species at the methane seeps in Costa Rica since 2009, 48 of which are newly-discovered species. Methane seeps are areas where bubbles of methane, a type of greenhouse gas, escape from rocks or sediment in the seafloor. They can host a diverse ecosystem of animals that feed on food produced by methane-consuming bacteria.

"We've spent years trying to name and describe the biodiversity of the deep sea," study co-author Greg Rouse, a marine biologist at the University of California, San Diego's Scripps Institution of Oceanography, said in the statement.

"At this point we have found more new species than we have time to name and describe," he said. "It just shows how much undiscovered biodiversity is out there. We need to keep exploring the deep sea and to protect it."

The team is planning to head back out to sea later this year with the hope of making more deep-sea discoveries at methane seeps off the coasts of Alaska and Chile.