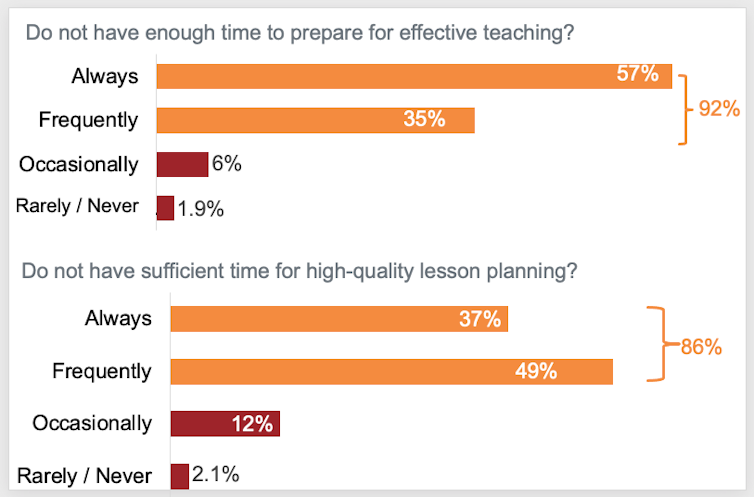

Almost all teachers (92%) in our study out today said they don’t have enough time to prepare effectively for classroom teaching – the core of their job.

The Grattan Institute surveyed 5,442 Australian teachers and school leaders across all states and territories, primary and secondary schools, and government and non-government schools. The survey was about teachers’ use of time.

Teachers told us they are too stretched to do everything we ask of them. When teachers aren’t supported to do their jobs well, teaching quality suffers and students lose out.

Beyond preparation for effective teaching, 86% of teachers reported they didn’t have time for high-quality lesson planning.

Teachers say they don’t have time to prepare well for lessons

Our findings consistently show many teachers feel overwhelmed by everything they are expected to achieve. One teacher told us:

[There is] not enough planning time to allow for how responsive we need to be to students’ needs.

Many teachers, especially at disadvantaged schools, said they get too little support to help struggling students.

And many teachers point to heavy requirements relating to writing reports, communicating with parents and supporting student welfare. One teacher said:

Administration time takes up most of planning time – such as communication to parents, newsletters, displays, notes, permission slips, phone calls and talking to students about well-being issues.

Teachers’ struggle with workload is not caused by a lack of effort – Australian teachers work hard. Census data show teachers in Australia work about 44 hours a week on average – much more than the 40 hours of general professionals.

Australian teachers’ working hours are high by international standards, too. OECD data show Australian secondary teachers work an average of 45 hours a week, compared to the international average of 40 hours.

Read more: 'Exhausted beyond measure': what teachers are saying about COVID-19 and the disruption to education

Our survey also found school leaders are aware of the pressure on teachers’ time, but feel powerless to do much about it.

We cannot expect each of the 9,500 schools around Australia to solve these challenges on their own. Governments must step up. Our report, Making time for great teaching, recommends governments adopt three reform directions.

1. Find ways other school staff can take on non-teaching work

Governments need to better match teachers’ work to their expertise. To do this, they should find better ways to use the wider schools workforce, including support and specialist staff, to help teachers focus on effective teaching.

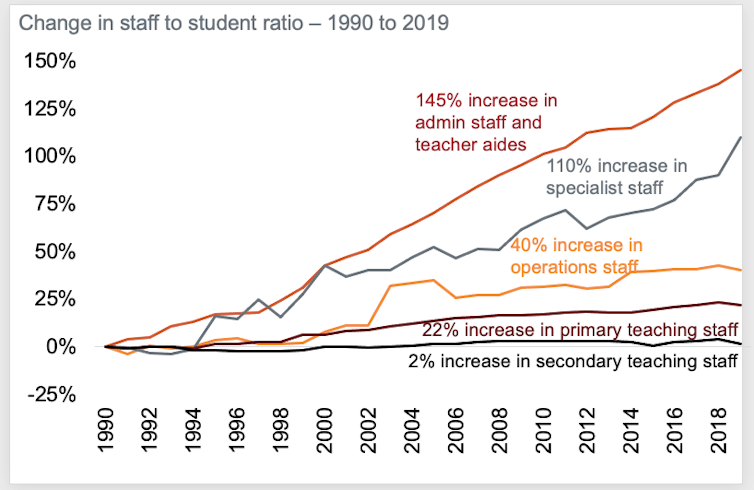

Significant numbers of support and specialist staff have been added to schools over the past few decades. But governments have not tracked the best way to deploy and use them well.

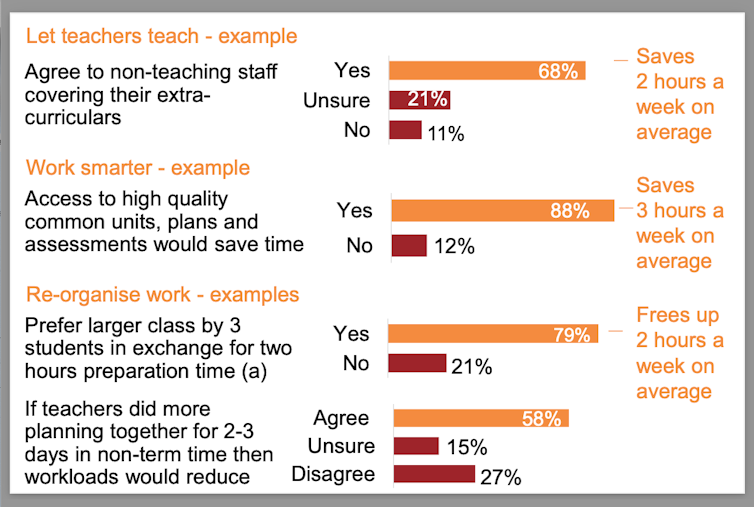

In our survey about 68% of teachers agreed support staff could cover their extra-curricular activities. We estimate this would free up an additional two hours a week for teachers.

2. Help teachers reduce unnecessary tasks

Teachers consistently say they feel overburdened by administration. Streamlining administration where possible is important. But there are also significant opportunities to improve how teacher time is spent on core teaching-related work.

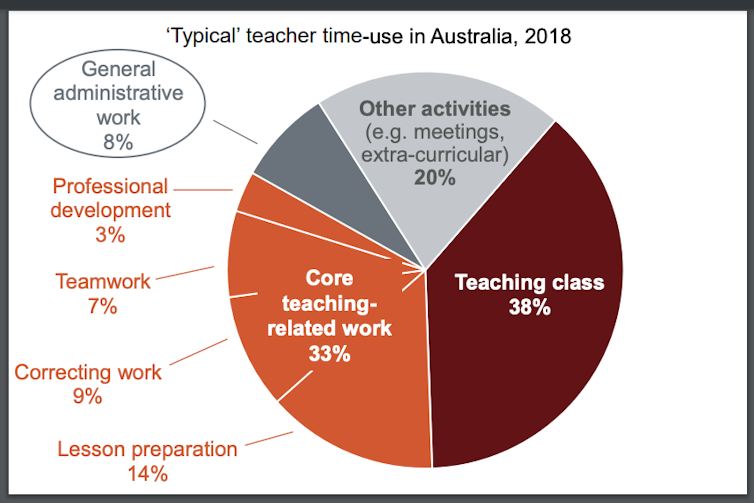

According to the OECD’s Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS), Australian teachers spend about one-third of their time each week on core teaching activities such as correcting student work, preparing for lessons, teamwork and professional development.

This is four times as much as the time spent on general administration (8%), so any improvements in core teaching work could potentially free up large amounts of time.

Teachers don’t spend enough time actually teaching

Lesson preparation is one of the key activities teachers do weekly. Yet more than half of teachers say this involves a lot of searching for and creating their own curriculum unit and lesson plans, assessments and classroom resources. This work eats up a lot of time and is a significant barrier to teachers feeling prepared for the classroom.

Almost 90% of teachers agreed that having high-quality common resources for curriculum and lesson planning would help reduce their planning burden. This would free up an extra three hours a week.

3. Rethink how teachers’ work is organised

Policy decisions and industrial agreements shape the fundamental ways teachers’ work is organised in schools. For example, they set the number of face-to-face teaching hours required each week, the number of students in each class and expectations about the work teachers do during term breaks.

Governments should ensure school leaders have the flexibility to rethink teachers’ work in ways that open up more preparation time. For example, school leaders should have the flexibility to make small increases in class sizes (say by two to three students). Most teachers said they were in favour of slight increases in class sizes in exchange for two hours of extra preparation time each week.

Read more: Making better use of Australia's top teachers will improve student outcomes: here's how to do it

School leaders should also have flexibility to schedule more structured preparation and planning activities in non-term time. In our survey 58% of teachers agreed working together for two or three extra days before each term could reduce their workloads during term.

Teachers agreed with several reforms

What next

Our report calls on Australian governments to commit to a $60 million program to investigate and pilot the concrete options, including those tested in our report, that create more time for great teaching. That investment would be a tiny fraction (less than 0.1%) of the $65 billion Australia’s governments spend each year on school. This is a small price to pay to improve the way our schools operate and ease the workload burden on teachers.

Making sure teachers have enough time for great teaching should be a national imperative.

We thank the Origin Energy Foundation for their generous support for this project. Julie Sonnemann is also a Board Director of The Song Room, a not-for-profit organisation

Rebecca Joiner does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.