We destroyed many of our natural ecosystems fast in Aotearoa, driving them from pristine to near-dead. Now it’s time for us to show we are fast-learners at helping nature to recover

Opinion: Matariki is a very welcome and much needed new celebration for us a nation. As the start of nature’s new year – from here nights shorten and days lengthen – it is a moment for thanksgiving for the end of one annual cycle of life and the beginning of the next.

It is the time each year for us to sow seeds, plant crops and begin new projects. Literally if we’re farmers and gardeners who work with nature’s other great gifts of life such soil and water, plants and animals.

But literally also for those of us who buy all our food from shops. Our lives utterly depend on nature and the living systems of the Earth, whether we are rural or urban people. Matariki is the right moment each year to remind ourselves of our dependence and to renew our resolve to re-establish our right relationship with nature.

If you’re in any doubt about our desperately urgent need to do so, watch the Breaking Boundaries: the science of our planet documentary on Netflix by Sir David Attenborough and Johan Rockström; or read their book.

Attenborough you’ll know well; Rockström you won’t, yet he is a pioneer of one the newer areas of Western science which dates from only the early 1980s. It is Earth system science which is rapidly increasing our understanding of how intensely nature’s prolific, complex and varied systems depend on each other for survival. They constitute the living Earth, our life support system.

Earth system science is mātauranga Pākehā, western knowledge. But we are latecomers to such insights, albeit bringing deep new knowledge even down to the sub-atomic level. Long before us, indigenous peoples around the world came to understand the rhythms and cycles of life through intense observation of nature, handed down from generation to generation. They never lost sight of the big picture, the systems, and how to live their lives within them.

"When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe." – John Muir

Western science is belatedly coming to understand, and to benefit from, such knowledge and wisdom. For example, the United Nation’s 6th (and current) round of climate crisis assessment reports draws more than ever before on such sources.

Here in Aotearoa we’re showing how these two knowledge systems can inform each other as they seek together to understand then solve complex problems in nature we humans have caused. Some of the best examples are in the 11 National Science Challenges, each of which has decade-long, inter-disciplinary, well-funded goals to help us solve matters of sustainability in nature, in humans, and in the interaction between them.

To do so they are bringing together mātauranga Māori and mātauranga Pākehā, to the benefit of both and their end goals. For example, the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge does this by committing to “the Māori world view (Te Ao Māori) [that] acknowledges the interconnectedness and interrelationship of all living and non-living things.” Collectively, the 11 Challenges have produced this guide to such work across their wide fields.

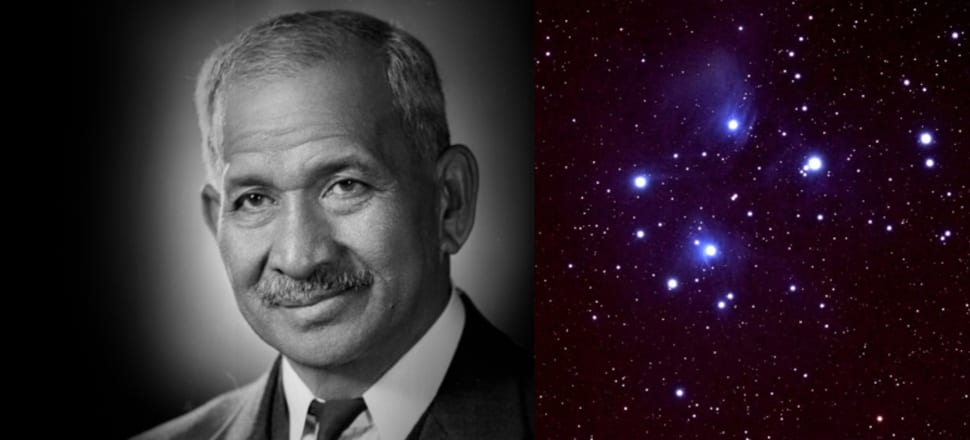

In one sense this is old wisdom. Back in 1900, Āpirana Ngata, the Ngāti Porou leader and scholar, wrote of mātauranga Māori and mātauranga Pākehā and the great benefit of "casting our nets between them", rather than fishing in one or the other.

Another fascinating example is the Environment Aotearoa 2022, the latest version of our triennial report on the health of our ecosystems and the impact of human activity on them.

It uses Te Ao Māori as its overarching structure to present the scientific data we collect on 48 measures of ecosystem health; to describe the relationships between them that determine the overall state of nature; and then to highlight how that contributes to our wellbeing – environmentally and economically, socially and culturally.

To do so, it uses Te Kāhui o Matariki (the Matariki star cluster) as a way to present its evidence. Each of the stars in it represents a way we connect with the environment. And as a signal of the Māori new year, Matariki commemorates loss and celebrates hope for the future.

These are examples of our particular gift to the world on how to ensure indigenous and western knowledge enhance each other so we can better rediscover our right relationship with nature.

Aotearoa was the last large land mass on the planet to be settled by humans barely 30 generations ago. Over that time, we greatly modified those ecosystems, then latterly we have deeply exploited and degraded them.

Perhaps just in the nick of time, we’re starting to commit to helping nature recover. Thanks to Te Ao Māori and mātauranga Māori we have a wealth of indigenous knowledge to help guide us.

Unusually compared with indigenous knowledge elsewhere in the world, it was gathered in a remarkably short time in ecosystem terms. Thus, Māori have extensive knowledge and narrative of the way we fast-forwarded the destruction of nature in many of our ecosystems, driving them, from pristine to near-dead. Now it’s time for us to show we are fast-learners at helping nature to recover.

Every society across the living Earth has the same monumental challenge for survival. The first glimmer of understanding every human needs is that their life utterly depends on nature. If nature’s healthy, they’re healthy.

Nature has given us this moment each year at Matariki to remind ourselves of our symbiotic relationships with and dependence on nature. Te Ao Māori’s stories of the stars tell us profound truths in poetic ways.

And these are universal truths. Astronomers calculate from the likes of cave paintings of the stars that they – whether you call them Te Kāhui o Matariki, or the Pleiades, or Subaru (as the Japanese do) or other names in other cultures – are the oldest proven source of human stories dating back some 100,000 years.

As John Muir, the Scottish-born, early 20th century US environmentalist wrote in his 1911 book My First Summer in the Sierra: "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe."