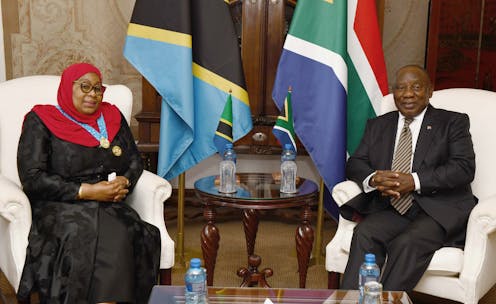

Tanzania’s President Samia Suluhu Hassan recently paid a state visit to South Africa aimed at strengthening bilateral political and trade relations. As the South African presidency noted, ties between the two nations date back to Tanzania’s solidarity with the anti-apartheid struggle.

This history is an important reminder of the anti-colonial and pan-African bonds underpinning international solidarity with southern African liberation struggles. It’s also a reminder of the sacrifices many African countries made to realise continental freedom.

Tanganyika, as Tanzania was known before independence in 1961, was the first safe post for South Africans fleeing in the aftermath of the Sharpeville massacre on 21 March 1960, when apartheid police shot dead 69 peaceful protesters. The apartheid regime banned liberation movements shortly thereafter.

Among those who left South Africa to rally international support for the liberation struggle were then African National Congress deputy president Oliver Reginald Tambo, Communist Party and Indian Congress leader Yusuf Mohammed Dadoo, and the Pan Africanist Congress’s Nana Mahomo and Peter Molotsi.

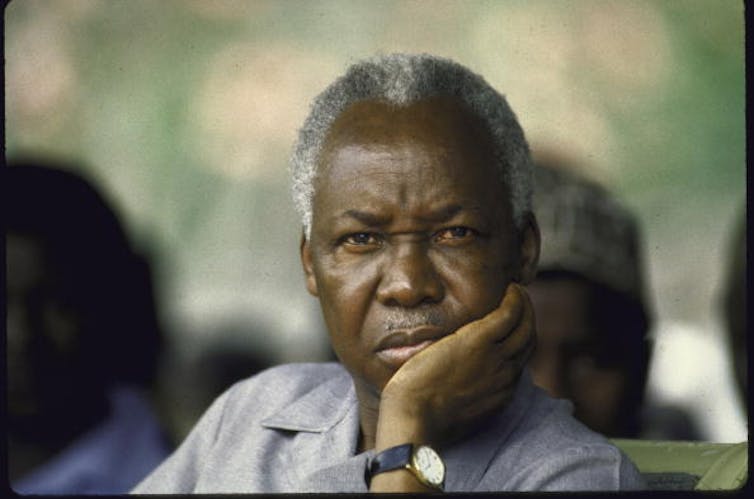

Not many people will know that on 26 June 1959 Julius Nyerere, the future president of Tanzania, was among the speakers at a meeting in London where the first boycott of South African goods in Britain was launched. Out of this campaign, the British Anti-Apartheid Movement was born a year later. It spearheaded the international solidarity movement in western countries over the next three decades.

Liberation struggle bonds

Tanzania’s support for South Africa’s liberation struggle needs to be understood as part of its broader opposition to colonialism, and commitment to the achievement of independence in the entire African continent. In 1958, Nyerere helped establish the Pan African Freedom Movement of Eastern and Central Africa to coordinate activities in this regard. This was extended to the Pan African Freedom Movement of Eastern and Central and Southern Africa at a conference in Addis Ababa in 1962. Nelson Mandela addressed the conference with the aim of arranging support for the armed struggle in South Africa. These efforts eventually led to the creation of the Organisation for African Unity (OAU) in 1963.

In February 1961, James Hadebe for the ANC and Gaur Radebe for the PAC opened an office in Dar es Salaam representing the South African United Front. It was the first external structure set up by the two liberation movements. Their unity was short-lived. But, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s capital, grew into a centre of anti-colonial activity after independence from Britain in December 1961.

At independence, Tanzania faced a shortage of nurses as British nurses left in droves rather than work for an African government. On President Nyerere’s request, Tambo arranged the underground recruitment of 20 South African nurses (“the 20 Nightingales”) to work in Tanzanian hospitals. The remains of one of them, Kholeka Tunyiswa, who died on 5 March 2023 in Dar es Salaam, were repatriated to South Africa for reburial in her home city of Gqeberha, Eastern Cape.

In the early 1960s, Tanzania was the southernmost independent African country from which armed operations could be carried out into unliberated territories in southern Africa. Its capital was chosen as the operational base of the OAU’s Liberation Committee. The committee provided financial and material assistance to liberation movements. Its archives remain in Tanzania.

In 1963, the ANC officially established its Tanzania mission, with headquarters in Dar es Salaam. A military camp for guerrillas of its armed wing, uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) , who had returned from training in other African and socialist countries, was opened in Kongwa. The Tanzanian government donated the land.

Also stationed there were the armies of other southern African liberation movements – ZAPU, Frelimo, SWAPO and the MPLA.

In 1964, the PAC also moved its external headquarters to Dar es Salaam after it was pushed out of Lesotho. It established military camps near Mbeya and later in Mgagao, and a settlement in Ruvu. Both the PAC and the ANC held important conferences in Tanzania, in Moshi in 1967 and in Morogoro in 1969, respectively. These led to internal reorganisation and new strategic positions.

Hitches in the relationship

In spite of Tanzania’s support for the liberation movements, their relationship was not without its contradictions or moments of ambivalence.

In 1965, for example, the ANC had to move its headquarters from Dar es Salaam to Morogoro, a small upcountry town far from international connections. The Tanzanian government had decided that only four members of each liberation movement would be allowed to maintain an office in the capital. This reflected Tanzania’s anxiety over the growing numbers of revolutionaries and trained guerrillas it hosted.

In 1969 Tanzania, Zambia and 12 other African countries issued the Lusaka manifesto, which was also adopted by the OAU. It expressed preference for a peaceful solution to the conflict in South Africa over armed struggle. There were also rumours of ANC involvement in an attempted coup against Nyerere. In this climate, the ANC had to evacuate its entire army to the Soviet Union. Its soldiers were allowed back in the country a couple of years later.

Lived spaces of solidarity

In the 1970s, ANC headquarters moved to Lusaka, in Zambia, and uMkhonto we Sizwe operations moved to newly independent Angola and Mozambique. But Tanzania remained a significant place of settlement for South African exiles.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, additional land donations from the Tanzanian government enabled the ANC to open a school and a vocational centre near Morogoro. The Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College in Mazimbu and the Dakawa Development Centre were set up to address the outflow of young people from South Africa following the June 1976 Soweto uprising. Its other aim was to counter the effects of Bantu education, a segregated and inferior education system for black South Africans.

These became unique spaces of lived solidarity between the ANC and its international supporters. They accommodated up to 5,000 South Africans. Some of them died before they could see a liberated South Africa. Their graves are in Mazimbu. Besides educational facilities, the camps included an hospital, a productive farm, workshops and factories. They were all developed with donor funding.

Tanzanians, too, contributed to these projects through their labour. Many Tanzanian women became entangled in South Africa’s liberation struggle through intimate relationships, marriage and children. Thanks to these everyday social interactions, Tanzania became “home” for many South African exiles. The ANC handed over the facilities at Somafco and Dakawa to the Tanzanian government on the eve of the first democratic elections in 1994. But these personal and affective connections live on.

Arianna Lissoni does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.