Our food choices are being influenced every day. On social media platforms such as YouTube, Instagram and TikTok, food and eating consistently appear on lists of trending topics.

Food has eye-catching appeal and is a universal experience. Everyone has to eat. In recent years, viral recipes like feta pasta, dalgona coffee and butter boards have taken the world by storm.

Yet food influencing is not a new trend.

Australia’s first food influencer appeared in the pages of Australia’s most popular women’s magazine nearly 70 years ago. Just like today’s creators on Instagram and TikTok, this teenage cook advised her audience what was good to eat and how to make it.

À lire aussi : How the Australian Women's Weekly spoke to '50s housewives about the Cold War

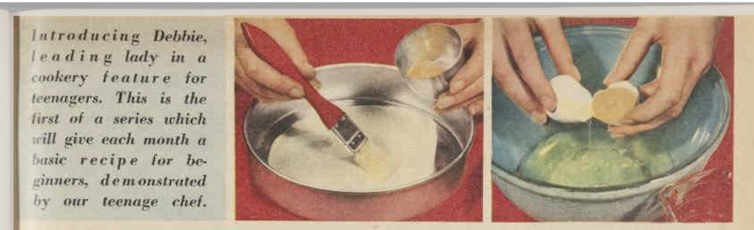

Meet Debbie, our teenage chef

Debbie commenced her decade-long tenure at the Australian Women’s Weekly in July 1954. We don’t know exactly who played the role of Debbie, which was a pseudonym. Readers were never shown her full face or body – just a set of disembodied hands making various recipes and, eventually, a cartoon portrait.

Like many food influencers today, Debbie was not an “expert” – she was a teenager herself. She taught teenage girls simple yet fashionable recipes they could cook to impress their family and friends, especially boys.

She shared recipes for tangy apricot Bavarian whip, fried rice medley and bombe Alaska. Debbie also often taught her readers the basics, like how to boil an egg.

Just like today, many of her recipes showed the readers step-by-step instructions through images.

Teaching girls to cook (and be ‘good’ women)

Debbie’s recipes first appeared in the For Teenagers section, which would go on to become the Teenagers Weekly lift-out in 1959.

These lift-outs reflected a major change taking place in wider society: the idea of “teenagers” being their own group with specific interests and behaviours had entered the popular imagination.

Debbie was speaking directly to teenage girls. Adolescents are still forming both their culinary and cultural tastes. They are forming their identities.

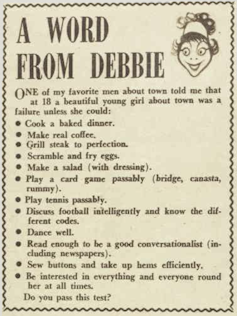

For the Women’s Weekly, and for Debbie, cooking was deemed an essential attribute for women. Girls were seen to be “failures” if they couldn’t at least “cook a baked dinner”, “make real coffee”, “grill a steak to perfection”, “scramble and fry eggs” and “make a salad (with dressing)”.

In addition to teaching girls how to cook, Debbie also taught girls how to catch a husband and become a good wife, a reflection of cultural expectations for women at the time.

Her macaroon trifle, the Women’s Weekly said, was sure to place girls at the top of their male friends’ “matrimony prospect” list!

À lire aussi : More than just MasterChef: a brief history of Australian cookery competitions

Food fads and fashions

Food fads usually reflect something important about the world around us. During global COVID lockdowns, we saw a rise in sourdough bread-making as people embraced carbohydrate-driven nostalgia in the face of anxiety.

A peek at Debbie’s culinary repertoire can reveal some of the cultural phenomena that impacted Australian teenagers in the 1950s and ‘60s.

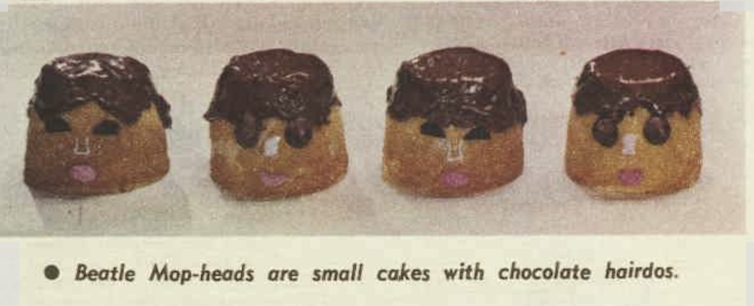

Debbie embraced teenage interest in rock'n'roll culture from the early 1960s, the pinnacle of which came at the height of Beatlemania.

The Beatles toured Australia in June 1964. To help her teenage readers celebrate their visit, Debbie wrote an editorial on how to host a Beatles party.

She suggested the party host impress their friends by making “Beatle lollipops”, “Ringo Starrs” (decorated biscuits) and terrifying-looking “Beatle mop-heads” (cakes with chocolate hair).

A few months later, she also shared recipes for “jam butties” (or sandwiches, apparently a “Mersey food with a Mersey name”) and a “Beatle burger”.

We can also see the introduction of one of Australia’s most beloved dishes in Debbie’s recipes.

In 1957, she showed her teen readers how to make a new dish – spaghetti bolognaise – which had first appeared in the magazine five years prior.

Debbie was influencing the youth of Australia to enthusiastically adopt (and adapt) Italian-style cuisine. It stuck. While the recipe may have evolved, in 2012, Meat and Livestock Australia reported that 38% of Australian homes ate “spag bol” at least once a week.

Our food influences today may come from social media, but we shouldn’t forget the impact early influencers such as Debbie had on young people in the past.

À lire aussi : Getting creative with less. Recipe lessons from the Australian Women's Weekly during wartime

Lauren Samuelsson received funding from an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship when undertaking this research.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.