Vyjayanthimala clad in an incandescent green saree teases a glance as a fish bowl and its silvery-gold inhabitants in the background stand witness. This canvas is signed: M Ramalingam. An archetype of 1980s Tamil cinema and its dramatic allure, this frame frozen in paint, speaks volumes: of a glorious time of hand-drawn skills that later morphed into the thriving industry of calendar art in South India. Ramalingam was one of its most prolific stars.

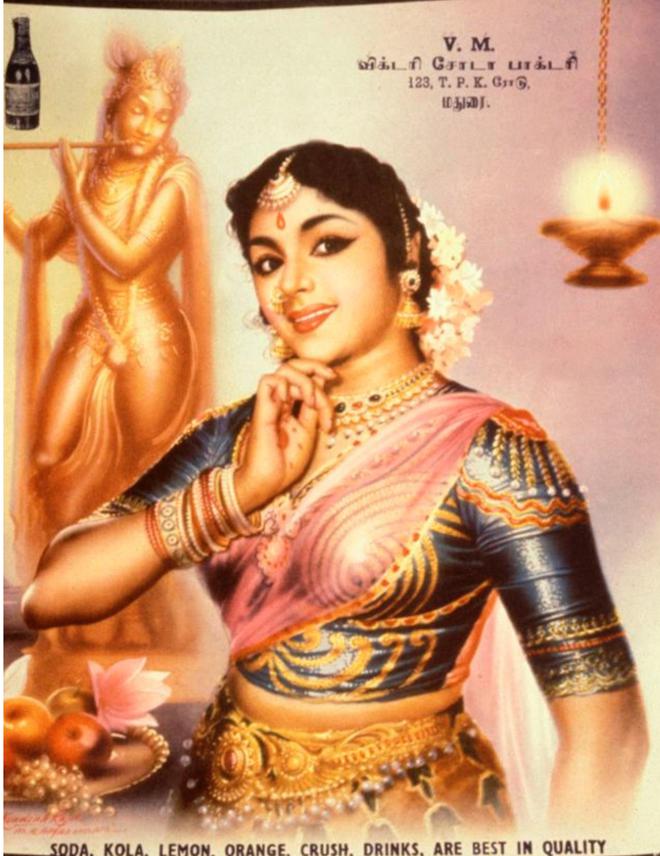

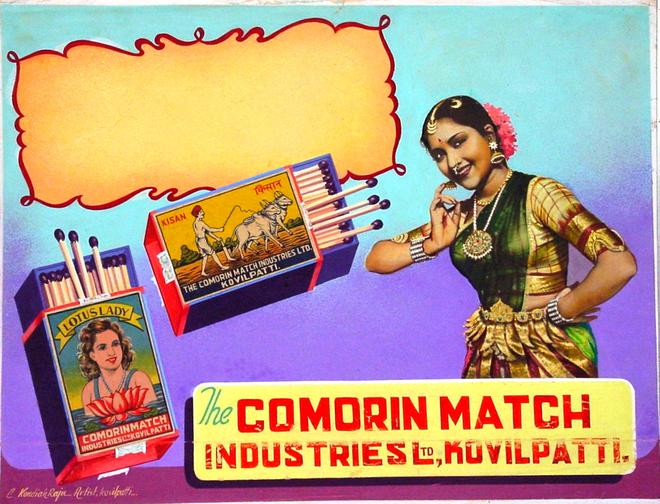

Today, in the bylanes of the dusty, metro work-laden Arcot Road in Chennai is Chithiraalayam, an unassuming gallery brimming with familiar canvases and prints. By familiar, I don’t mean in the style of Razas and Husains. Rather, it is the kind of familiarity you associate with a dear object at home that you have known for decades. In the gallery are many ‘saami padams’ (as they were known in the 1940s) by some of the stalwarts and pioneers of the calendar art industry, all hailing from the school of C Kondiah Raju. Think Muruga with a smile on his face against a glittery backdrop, and other Hindu gods and goddesses, apart from scenes from popular Indian mythology like that of the churning of the ocean.

Chithiraalayam is a study on this school of artists that never got its due and of an industry that faded around the end of the 20th Century. A part of the collection is on display today at DakshinaChitra, as an ode to its forgotten masters.

Painted history

Calendar art found space in most Indian households in the early 20th Century, as they were often distributed for free by retail stores selling textile, jewellery and sweets ordering calendars to give to customers. But little was known about the hands that drew them. “It is an industry that never got registered in art history,” says KR Jayakumar, the youngest son of Ramalingam whose vision for this commercial art gallery is awareness more than revenue: for now, all the works here are only for display and documentation.

As Raja Ravi Varma, one of the pioneers of popular art in the country, earned steady acclaim for bringing European academic art styles onto Indian themes, and portraying characters from The Mahabharata and the The Ramayana, a quieter revolution was underway in the sidelines, impinged on portraying divinity.

The legacy goes back to the 1940s when popular art in Kovilpatti got a name under C Kondiah Raju who started out by painting backdrops for travelling theatre companies. Shortly after, he set up photo studios (Sri Ambal Arts in 1944 and Devi Art Studio in 1946) that would see a rush for portraits, which were often drawn in or finished up by the fine hand skill of his students: TS Subbiah, S Meenakshisundaram, TS Arunachalam, M Ramalingam, G Shenbagaraman, M Sreenivasen and TS Rajagopal Raju.

Then came Muruga purnas (different manifestation of lord Muruga) and Hindu mythological scenes, a lot of them dominated by goddesses. “There has always been a tension and thus an attraction to the female as a deity and as a beauty,” says Stephen Inglis, a professor at Carleton University in Ottawa, Canada. “As an anthropologist studying potter communities in Madurai/Ramnad, I saw popular imagery everywhere: in temples, schools, shops, and people’s homes. I wanted to know more,” says Stephen, who is also the curator of the show at DakshinaChitra.

It was the ubiquity of distribution and the use and juxtaposition of imagery that invited Stephen to look at calendar art specifically. The advent of printing presses in Sivakasi (known for its dry climate which made it an ideal location for printing apart from matchstick production) meant an increase in both production and demand.

“Every year, around the month of aadi, almost 120 printers would pick up bound albums with sample artworks to show their clients,” says Somasundaram, artist and oldest son of Ramalingam as he flips through a colourful collection of sample artworks from 1997. It holds some Christian iconography, paintings of mosques apart from landscapes and pictures of actresses: from Madhuri Dixit to Urvasi.

Over the years, influences of photography, superimposition, cinema and even the advent of spray cans can be seen on these canvases. So much so that a Muruga with a pink-and-golden, patterned backdrop had, believe it or not, a crystal bowl for inspiration. The cut-glass pattern behind the form of Muruga became very popular in the late 1980s, says Somasundaram. Photographs of ornate temple gopurams were another popular trope for backdrops.

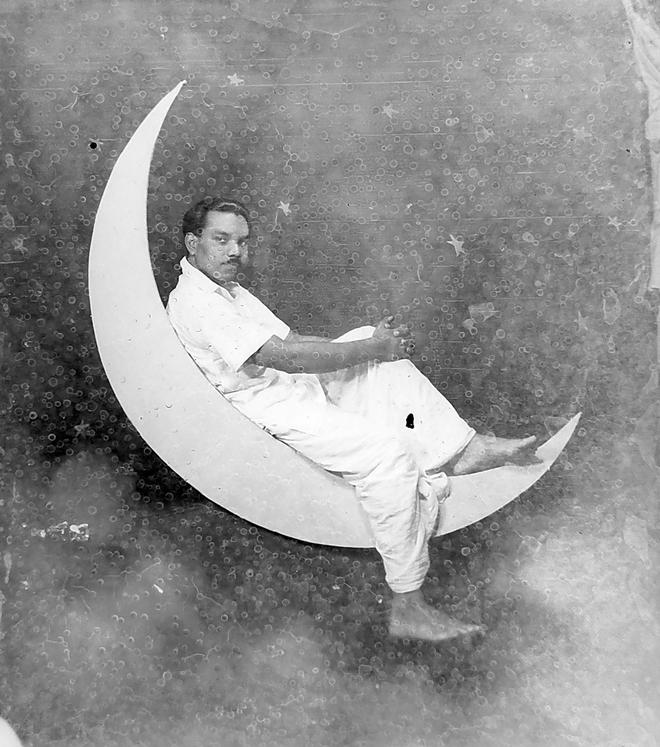

Ramalingam created over 1,400 pieces in his time, and over 1 lakh prints of each have been circulated over the years. “Our father passed away in 1993, but his prints were still in circulation until 2003,” says Jayakumar. TS Subbiah followed closely. “Every artist had their own set of challenges,” says Marieswaran, artist and son of TS Subbiah as he looks at a black and white portrait of the artist reclining on a crescent moon, perhaps a prop from a drama set: he was inspired by the grandiose of theatre.

“And, with religious subjects, there is an unspoken guarantee of every piece being a reverent keepsake. Till today, some household prayer rooms are home to these calendars,” says Marieswaran.

The road ahead

The earliest original work in Chithiraalayam is dated to 1955. It took Jayakumar almost eight years to find and source at least some of his father’s original works. ”I approached the presses that my father was regularly in touch with. The main contributors were Coronation, Orient and Das printers who had some of the originals intact,” says Jayakumar. While prints were easier to collect, the originals, of which almost 60 are on display, were hard to spot.

The industry began to fade out at the end of the 20th Century. Says Stephen, “The presses that typically acquired the original paintings had a volume that, with some retouching, could meet their needs. The digital ease with which paintings and photographs could be supplied made the painting phase obsolete. Calendars were replaced by cell phones.”

Today, a couple of tall wooden easels stand guard to a low plank on which is an unfinished canvas: the chair is empty, yet carries the weight of an industry that revolutionised commercial art. This was Ramalingam’s workspace: the gallery hosts a replica of the workspace as it was in the early 20th Century. Jayakumar reminisces, “There would always be a small bowl of off white or ivory paint near the canvas, on the desk. Everyday after school, I would watch his speed in placing the paints on the first coat.”

Now, efforts are on to celebrate the printed picture as a key artform of the 20th Century, says Inglis. “It is by learning about the artists and their work, and celebrating their contribution that any revival is possible.”