Michael Garrett had been incarcerated since 1994 and had suffered nightly, unable to get any real rest for nearly 20 years before he decided to sue the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ). He told his mother he was going to change the system. He would stand against policies that forced people to choose between necessities like sleep, breakfast, or clean clothes. He had a high school diploma, and he had wanted to be a lawyer when he was younger. He felt he had the skills and experience to advocate for himself and others.

He remembers telling his mom that by the end of his efforts, the prison system might actually thank him. Today, he laughs as he recalls her response: “No way in hell.”

In March 2013, Garrett filed a federal lawsuit against TDCJ while he was housed at the McConnell Unit in South Texas. The suit said the prison’s 24-hour schedule was so packed and security checks so frequent that people inside were only being allowed about four hours of sleep per night, and even those were interrupted. The result is prolonged sleep deprivation that he says is damaging his health and violates his Eighth Amendment rights, which protect against cruel and unusual punishment.

Each night, Garrett struggles to fall and stay asleep. He lies in his bed and tries to block out the light and ignore the sounds—chatter among other prisoners, guards coming and going. But he can’t ignore the head count that happens just a couple of hours after he closes his eyes.

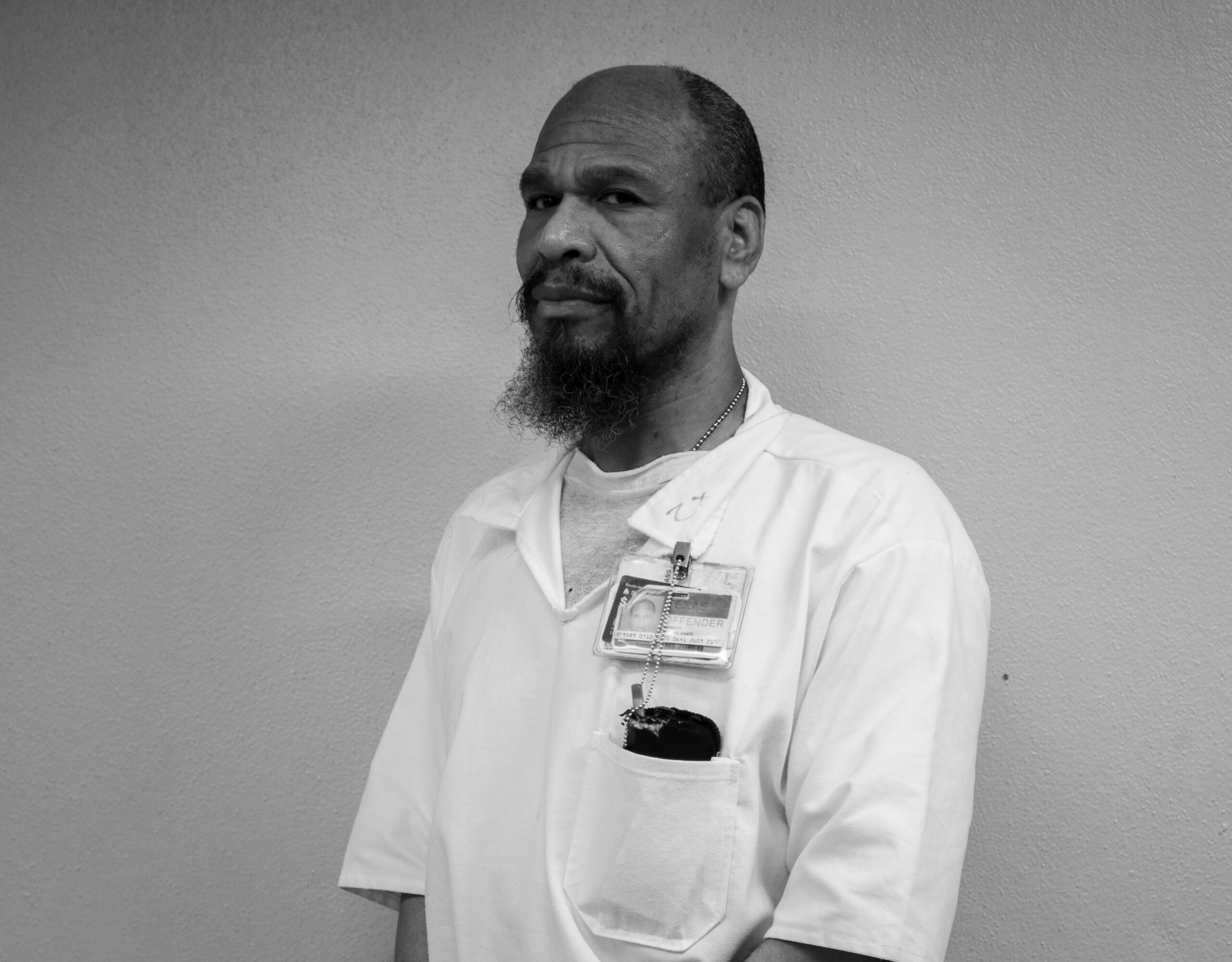

His case describes his migraine headaches, high blood pressure, and seizures, though in an interview Garrett seems far from frail. He’s tall and strongly built. His hair is shorn close to his scalp, and he sports a mustache and a mid-length beard that’s streaked with white on one side. He speaks softly but confidently about his case.

Now 54 years old, Garrett has been fighting the behemoth prison system in court for more than a decade.

Initially, he represented himself, later winning the support of a civil attorney, and he recently managed to get the conservative Fifth Circuit to side with him for a third time, something one of his lawyers said must be “some sort of record.” Three times, federal district court judges ruled against Garrett, saying there was no constitutional right to sleep in prison and that he couldn’t prove his medical conditions were caused by sleep deprivation or that TDCJ was “intentionally” or “wantonly” withholding sleep from people inside. And three times, the Fifth Circuit reversed these decisions. The courts, circuit judges repeatedly declared, couldn’t unfairly dismiss Garrett’s concerns.

Those victories are more remarkable given that during his first civil trial and appeal, Garrett did his own legal research, writing, and filings from his cell and the prison’s law library. Before the second civil trial, Garrett was appointed a criminal defense attorney, Naomi Howard, pro bono. Garrett’s would be her first civil case.

“He’s patient, and he is in it for the long term.”

But she said Garrett’s intelligence and his understanding of administrative and legal processes made her work easier. “I mean, the man survived the Fifth Circuit without any help from me,” she said, emphasizing his pro se legal victory.

The issue is compelling, but the case has endured because of his “will and determination,” Howard said. “He knows the rules. He knows the hurdles that lawyers face. He’s patient, and he is in it for the long term.”

Garrett was sentenced to life after being convicted of multiple felonies in Dallas and Collin counties—he talks about Dallas as where he “fell out.” He was born in Taos, New Mexico, and moved around often in his early years due to his dad’s job in the Air Force. To his father—a captain—education was paramount. Garrett graduated from Duncanville High School, in a suburb southwest of Dallas, then took a few college classes. “I wanted to be a lawyer, but I screwed up,” he said.

So he’s cobbled together his own legal education. As a teen and young adult, he studied to become a paralegal in Virginia and Colorado. While in prison, he took law classes online. He put his studies to use in his own case and, eventually, in others. Today, he’s housed in the Estelle Unit in Huntsville, where he’s been designated a legal liaison for veterans, helping incarcerated vets with any legal issues they have.

Garrett is part of a longstanding tradition of “writ writers” in Texas prisons. These are prisoners who engage with the legal system from inside and largely without lawyers’ help, filing petitions and motions related to their own or peers’ criminal cases, sometimes launching lawsuits based on alleged civil rights or constitutional violations.

In addition to helping other prisoners file briefs or appeals in attempts to reduce or overturn their sentences, Garrett, who is Jewish, has helped advance lawsuits against TDCJ related to its restrictions on religious facial hair and special diets.

“I’m supposed to do what it says in the Bible, help out, do the best I can,” he told the Texas Observer. “I’m not perfect … but I try my best. I try to do more right than I do wrong.”

When he first entered prison in the 1990s, the writ-writing culture was strong, Garrett said. At any time, if there were 50 chairs in the law library, all would be occupied by people furiously working on typewriters to meet filing deadlines. Now, writ writers seem to have a more complicated reputation among staff and other prisoners, he said. Despite this, Garrett can still be found in one of the prison library chairs. He’s worked hard to keep the sleep deprivation lawsuit going.

“I knew [the suit] was going to be a long road,” he told the Observer. “But I didn’t think it was going to be this long.” He said TDCJ has spent years in litigation to fight what he believes is a simple issue of broken policy.

Other incarcerated people learned of Garrett’s lawsuit while doing research for their own complaints about the prison’s sleep schedule. He said he’s helped some initiate their own grievances related to sleep deprivation.

As of mid-June, Garrett’s case against the prison system remains in limbo. The Fifth Circuit sided with Garrett in March, and the state has not indicated whether it plans to continue to appeal.

In the meantime, Garrett still faces the consequences.

Each night, as he gets into his bottom bunk bed, he forces himself to find some sense of calm. He’ll think back on a good conversation or recall a memory from before being locked up. Anything to distract himself from the ambient light, the sounds of the heavy mechanical gates opening and closing, the mosquitos coming in through cracked windows and making a meal of him. In his 9-by-5-foot cell—which he shares with a bunkmate—any comfort comes from his imagination.