Few fish can outswim a seal. Seals fly through the waves, predators in their natural element. But, unlike fish, seals are air-breathing mammals whose ancestors only returned to the water from a life on land some 30 million years ago.

On entering the water, seals had to adapt both their bodies and behaviour to become efficient underwater swimmers. Like penguins and sea turtles, they use streamlined limbs to propel themselves through the water.

Yet, there is a mystery here. Even though all seals and sea lions are descended from a common ancestor, they use two radically different modes of propulsion: true seals (phocids) swim with their feet; fur seals and sea lions (otariids) rely on their wing-like forelimbs.

How did these two related groups come up with such different swimming styles? Did they start from a common base, but then adapt to different circumstances? Or do we have it all wrong, and phocids and otariids have different ancestors after all?

To find out, we partnered with a team of engineers to combine cutting-edge computer simulations with anatomical and live animal observations. This multi-angled study, published today in Current Biology, allowed us to determine how, and how effectively, seals use their forelimbs during swimming.

Engineering a seal

Evolutionary biology and engineering might seem like strange bedfellows. Yet, ever since Leonardo Da Vinci, humans have sought to understand and adapt nature’s “designs”, giving rise to a field of engineering known today as biomimetics.

Engineering allows biologists to look beyond the mere shape of an animal, and instead ask how that shape is adapted to function within the physical limits set by its environment.

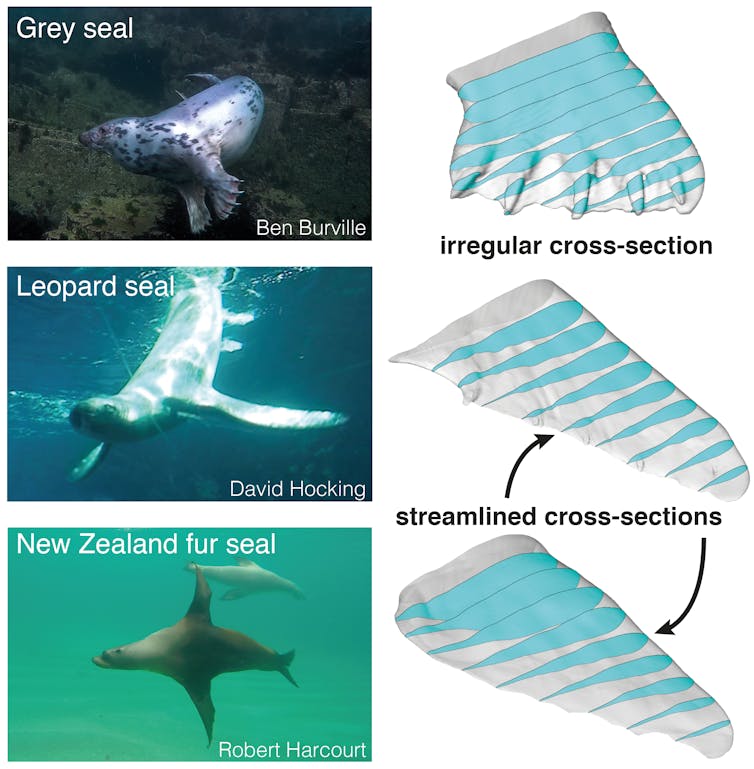

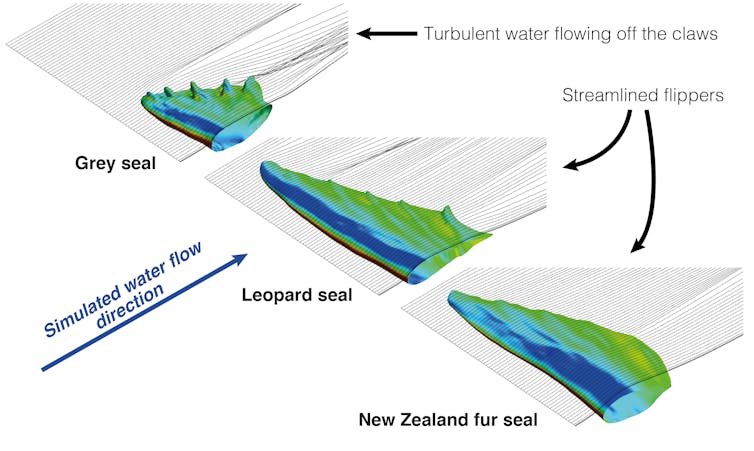

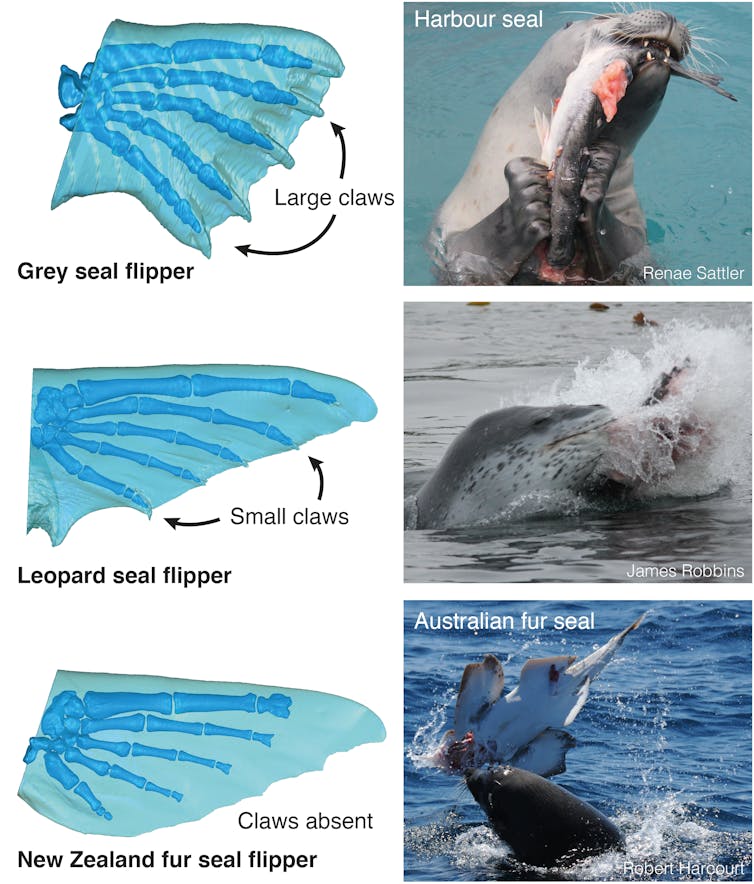

Applying this approach our question, we initially created 3D computer models of forelimb flippers representing each of the main seal families: from the bear-like paws of phocids (such as grey seals) to the wing-like flippers of fur seals and sea lions.

Next, we used computer-simulated fluid dynamics to model how water flows around the different flipper shapes. Perhaps unsurprisingly, we found the wing-like flippers of fur seals and sea lions produce little drag and considerable lift. The opposite is true of the clawed paws of true seals, which consequently make fairly poor tools for swimming.

Repeated evolution of forelimb flippers

So far, our results seem to confirm the fundamental difference between phocids and otariids. But there’s a twist to the story: streamlined fore-flippers are not unique to otariids.

Our results show that some rear-propelled Antarctic true seals independently evolved streamlined fore-flippers as well. This is taken to the extreme in leopard seals, whose flippers are almost indistinguishable from those of otariids. Out at sea, their massive forelimbs likely give them the speed and agility needed to pursue evasive prey such as penguins.

The independent appearance of flippers within southern true seals provides a clue to how forelimb swimming may have evolved in the first place.

Early seals probably swam with their feet and, like their terrestrial ancestors and northern true seals today, used their clawed forepaws to catch and eat large prey.

Over time, otariids and southern true seals independently began to chase faster, more agile prey. This would have required their forelimbs to assume a more active role during swimming, which manifested itself in greater streamlining, reduced claws and — in otariids — a complete switch from foot to flipper-based propulsion.

Read more: Sharp claws helped ancient seals conquer the oceans

So there you have it: perhaps seals use different swimming styles not because of separate evolutionary origins, but because they adapted to different environments. And it seems they did so more than once!

This theory makes a lot of sense in light of how seals behave and look today. Its litmus test likely lies elsewhere, however: buried beneath rocks, rather than frolicking beneath the waves. Only fossils can tell us what early seals were really like and, if our idea is correct, we should ultimately find some that match it. Only time will tell.

David Hocking receives funding from the Australian Research Council.

Alistair Evans receives funding from the Australian Research Council and Monash University, and is an Honorary Research Affiliate with Museums Victoria.

Hazel L. Richards receives an Australian government RTP scholarship.

Felix Georg Marx and Shibo Wang do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.