What astronomers thought was one of the oldest galaxies in the universe is actually two of them, according to new images from the James Webb Space Telescope.

A decade ago, Johns Hopkins University astronomer Dan Coe spotted a faint, distant galaxy called MACS0647-JD in images from the Hubble Space Telescope.

“It was just this pale, red dot. We could tell it was really small, just a tiny galaxy in the first 400 million years of the universe,” Coe says in a statement. In recent images from the James Webb Space Telescope, thanks to Webb’s higher resolution, astronomer Tiger Hsiao (also of Johns Hopkins University), Coe, and their colleagues could see that the pale, red dot was actually two separate — and very different — objects, about 1,300 light years apart.

They’ve published their results in a pre-print scientific paper, which hasn’t yet been through peer review.

What’s New — As they appeared more than 13 billion years ago, the larger object is blazing with the bright bluish-white light of newly-formed stars. The smaller one is redder and dimmer, full of older stars and swirling interstellar dust, which suggests it’s about 100 to 200 million years older than its younger, flashier companion.

“We’re actively discussing whether these are two galaxies or two clumps of stars within a galaxy,” says Coe. “We don’t know, but these are the questions that Webb is designed to help us answer.”

If they’re two separate galaxies, the narrow gap between them suggests that they may be headed for a cosmic mashup. And if they’re two very different neighborhoods of the same galaxy, it’s possible that we’re seeing the aftermath of a merger between two former galaxies.

“We might be witnessing a galaxy merger in the very early universe,” Hsiao says in a statement. “If this is the most distant merger, I will be really ecstatic.”

But wait — it gets even more dramatic. About 9,800 light years away from the mismatched pair, Hsiao and colleagues spotted another faint object. The astronomers behind the recent observation think it might be a third galaxy, in which case it’s probably destined for a merger with the first two.

Why It Matters — That’s an exciting prospect because galactic collisions may have played a key role in building the universe as we know it. Based on the few very old galaxies astronomers have found and studied so far, it seems that the universe’s first galaxies were very small (MACS0647-JD weighs in at a few hundred million times the mass of our Sun, compared to about 1.5 trillion for our much more modern Milky Way galaxy). As those small, early galaxies bumped into each other, they merged into larger and larger galaxies with more complex structures, like the barred spiral galaxy we call home.

And that process isn’t over yet; in about 5 billion years, the Milky Way galaxy will collide with the nearby Andromeda galaxy, and the end result will be an even bigger galaxy. The universe is still a work in progress. No matter how tempting it is to think of ourselves as the protagonists of some cosmic story, we’re actually living through a chapter somewhere in the middle, not the endgame.

Webb is helping astronomers see the earliest chapters of that story in much more detail.

What’s Next — “I think my favorite part is, for so many new Webb images we get, if you look in the background, there are all these little dots — and those are all galaxies. Every single one of them,” University of Texas astronomer Rebecca Larson, a co-author of the study, says in the statement. “It’s amazing the amount of information that we’re getting that we just weren’t able to see before.”

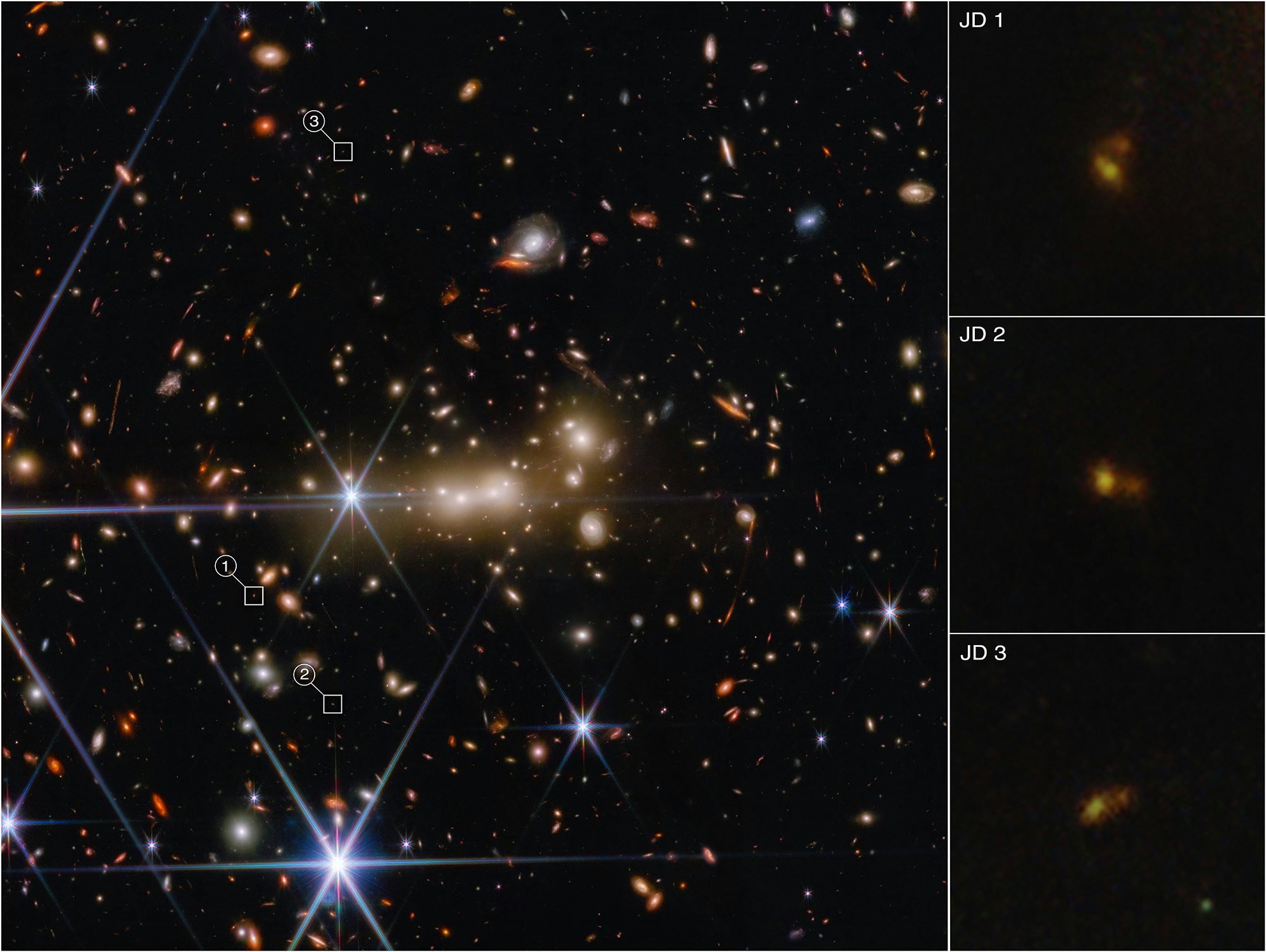

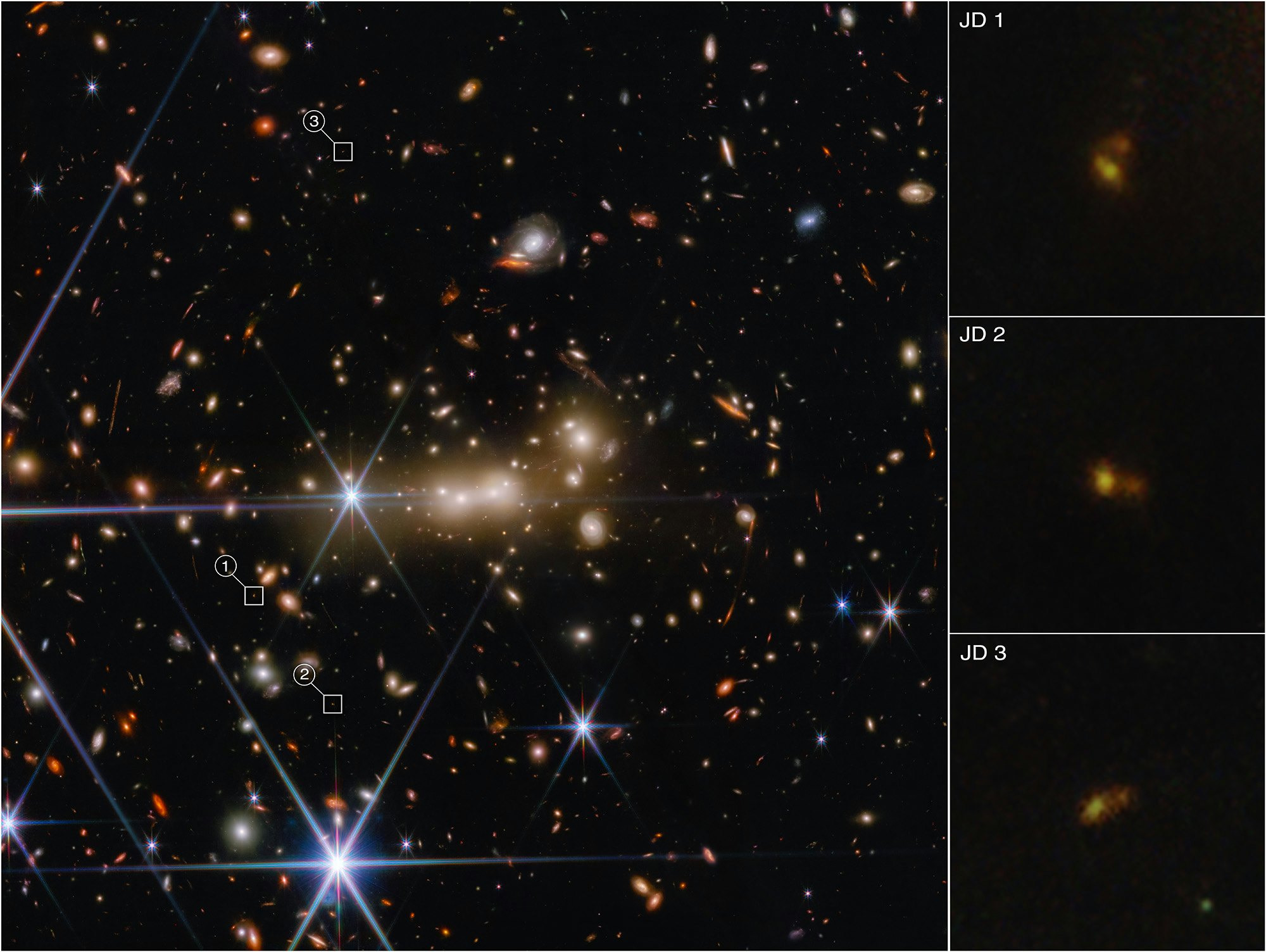

In the image that helped Hsiao and colleagues realize that MACS0647-JD was actually two objects, Webb got some help from a cluster of galaxies much closer to home (at least in cosmic terms; we’re still talking about something 6 billion light years away, or about halfway to the Big Bang). Webb used the galaxy cluster MACS0647 as a gravitational lens: an object so massive that its gravity actually bends light around it. The result is about the same as shining light through a curved glass lens; the image turns out bigger and brighter, but also slightly distorted.

For instance, MACS0647-JD showed up three times in the Webb image Hsiao and colleagues recently studied, each tilted at a different angle and magnified by a different amount — factors of 8, 5, and 2. Hubble used the same trick, and the same galaxy cluster, to image the distant red dot the first time around, but Webb’s more sensitive instruments were able to resolve the faint, faraway light into a much clearer, more detailed image.

“This is not a long exposure. We haven’t even really tried to use this telescope to look at one spot for a long time,” says Larson. “This is just the beginning.”

Hsiao and colleagues will point Webb at MACS0647 again in January 2023, when Webb’s instruments will gather more detailed information on the physical properties of MACS0647-JD. The team hopes that data will help them understand whether they’re seeing a galactic merger in progress.