Last September, Elma endured two days of sharp, intense pain in her stomach. The kind that brought on sweat and tears.

She avoided going to the hospital at first, knowing the bills would come soon after. Elma didn’t have health insurance.

But the 52-year-old Cicero resident said the pain became unbearable, fueling a 2 a.m. trip to MacNeal Hospital’s emergency department in west suburban Berwyn. Elma ultimately had her gallbladder removed. Her hospital stay would cost more than $50,000.

She thought constantly about the bills.

“The only time I feel any peace is when I’m asleep,” Elma said a few months after the surgery. (Her remarks have been translated from Spanish.) “The moment I wake up I’m asking myself, ‘How are we going to pay all this?’”

After the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights got involved, MacNeal would eventually write off 100% of its bill to Elma due to her low income.

But MacNeal’s bill forgiveness had its limits — it would not extend to the independent surgeons, anesthesiology group and other providers who also treated Elma. Those providers sent Elma their own bills, totaling more than $8,000.

What happened to Elma happens to many patients after they go to a hospital. Patients typically get one set of bills from the hospital and others from any independent physicians who treated them. Those doctors may have their own local practices or may be part of the increasing wave of physicians getting bought out by private equity groups to supply hospitals with staff. These doctors don’t typically get paid by the hospital, so they recoup their costs by directly billing patients.

And those bills can get really high. In recent years the chorus of complaints from patients with private insurance who were getting big bills from independent physicians or the companies they worked for grew so loud that Congress passed a federal law called the No Surprises Act that minimizes how large these bills can be.

But that law, which took effect Jan. 1, fell short of largely shielding the uninsured, who are the most likely population in the U.S. to have medical debt, according to a recent study from Kaiser. Some of the most vulnerable people who can least afford to pay can still face potentially crippling bills.

“One of the things that’s frustrating about this is that it’s just enough money to be devastating to the patient and very little money for the health system to collect,” said Carrie Chapman, senior director of policy and advocacy at the Legal Council for Health Justice in Chicago who advised on Elma’s case. “Relatively speaking, it’s less than a rounding error in their budget.”

She’s referring to bills ranging from $10,000 to $20,000. Some are much higher.

Experts around the nation who study medical billing and advocates for the uninsured say they’re hearing of more cases like Elma’s, though it’s hard to measure the scope of the issue. There’s no comprehensive tracking.

Chapman said she’s fielding a couple new cases like Elma’s a month, which she calls a “substantial uptick.”

Part of the problem is that a patient may not even know the doctor treating them is independent and may be billing them separately. In an emergency, patients might not have the ability to ask, might not know they can ask or even have a choice. What’s more, for the uninsured, how much they might have to pay for the medical care they receive depends on which hospital they wind up at.

Nonprofit hospitals are required by the IRS to provide so-called community benefits, such as discounts to low-income patients, in exchange for what can be lucrative tax breaks. WBEZ has previously documented how unequal these discounts are at hospitals across the region.

Now, WBEZ has found that hospital financial assistance policies spelling out their discounts vary widely, too. Many have long lists of doctors who aren’t bound by the hospitals’ policies. They’re the independent physicians, doctors groups and companies that can bill patients even if, like Elma, they get their entire hospital bill written off because they can’t afford to pay it.

Before AMITA Health recently broke into two hospital groups, this giant suburban hospital system had 49 pages of physicians, doctors groups and companies that weren’t covered by AMITA’s financial assistance policy. At prominent Northwestern Medicine, that list is 18 pages long. Nearly all of Silver Cross Hospital’s physicians in the southwest suburbs are excluded from having to provide discounts the hospital does.

Chapman questioned why hospital policies don’t extend to all providers who touch a patient.

“We need to be paying attention to and minding that store and seeing what is the benefit of our taxpayer bargain if hospitals are having for-profit corporations run their EDs, run their labs, run their radiology,” Chapman said. “We need to be deciding that maybe they don’t get 100% tax exemption, because they’re not using their property that way.”

The Illinois attorney general’s office, which helps regulate hospitals’ tax breaks, did not provide comment after multiple requests.

Taking on the bills, one by one

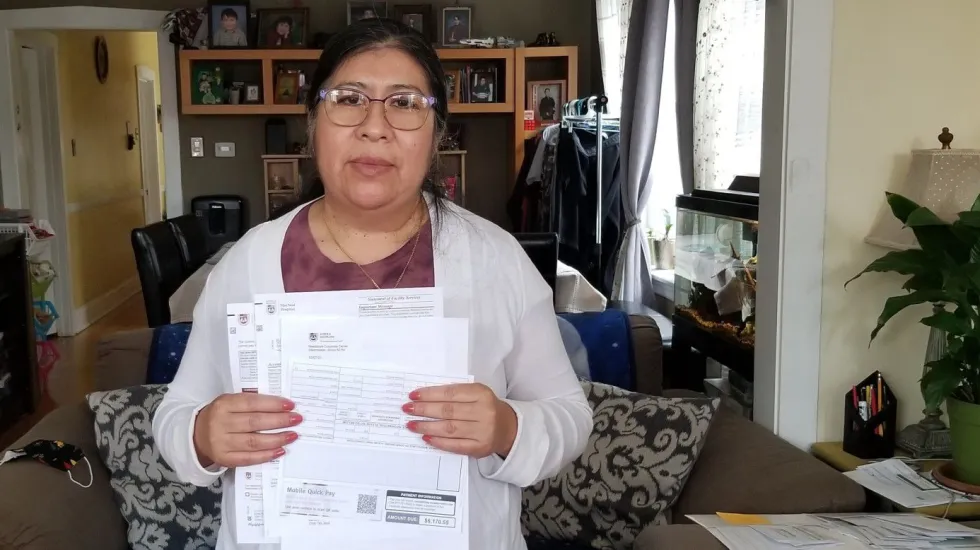

Elma tells her story one bill at a time. She kept them in a manila folder to track what she owed and how much she had paid. It’s not that she wasn’t willing to pay for the medical care she received — she was chipping away at the debt, as much as she said she could.

• $1,383 to Suburban Metabolic Institute for surgery

• $3,891.54 to MacNeal

• $6,170.55 to North American Partners in Anesthesia

Her list goes on.

WBEZ is not using Elma’s full name so as to not jeopardize her and her family. She is an undocumented immigrant, so she’s not eligible for health insurance through the government. She used to have insurance through her husband’s job, but she said the $500 monthly premiums were too expensive, so they dropped their coverage. Elma is a homemaker. Her husband works at a factory that makes elevator parts.

Elma’s independent providers encouraged her to set up payment plans, but she said she knew she wouldn’t be able to afford them, especially the anesthesia bill. These plans would just prolong how long she would be in debt.

Eventually, Elma found her way to Edith Avila Olea, policy manager with the Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights. After Avila Olea got involved, MacNeal erased Elma’s debt. The hospital encouraged Elma to share a letter from MacNeal with the independent providers who billed her, thinking they would offer the same discount.

Two providers did, zeroing out those bills. Additionally, the anesthesiology group knocked about $1,000 off its roughly $6,000 bill. The surgeons reduced their nearly $1,400 bill to just over $800.

Avila Olea has been keeping tabs of how widespread this issue is in the immigrant communities her organization and others like it work with. She sees a chilling effect.

“What’s scary is when they end up with these bills, if they need additional services, they are frightened to go back because they cannot afford another medical bill,” Avila Olea said.

Why hospitals, doctors say patients are getting big bills

WBEZ reached out to several hospitals to ask why their financial assistance policies don’t extend to every provider who treats patients. Some wouldn’t explain or in statements said they could not require independent providers to offer financial assistance but that many did on their own.

St. Bernard Hospital on Chicago’s South Side illustrates what is at stake, at least for this small hospital that has almost all independent doctors, if physicians were bound by the hospitals’ financial assistance rules.

“There’s a misperception about how much power a hospital has over providers,” said Mariann Grabe, director of patient financial services. “These are their patients.”

St. Bernard treats mostly low-income people in an area of the city with profound health disparities yet little access to medical care compared to the rest of Chicago. The hospital does not pay its mostly independent physician staff a salary, so doctors make money by billing patients, even if they don’t recoup much.

Hiring physicians, specialists in particular, can be expensive for a hospital like St. Bernard. Forcing a blanket financial policy on any doctor who worked there could make it hard to recruit them, Grabe said. It would be a paperwork nightmare, she added, if the hospital had to alert every provider that St. Bernard gave a discount for the patients’ care and suggest the independent physicians who treated those patients should, too.

Cook County’s public health system is among the few that doesn’t rely on independent physicians, while providing more discounted care than any other hospital by far in the region. The vast majority of Cook County Health’s providers are employed. The billing is coordinated by the county. Even the national staffing agency TeamHealth that has been recently contracted to work at the county’s Provident Hospital on the South Side won’t be billing patients separately, said Andrea Gibson, chief strategy officer at Cook County Health.

For many hospitals and health systems with deeper pockets, experts say it can be cheaper and more efficient to outsource medical care. That means contracting with staffing agencies to fill the ER and OR, and these companies then bill patients on their own.

But this can also create an empathetic divide, where a company doesn’t have a relationship with patients like a community doctor would and have a deeper conversation about what they can afford. In some cases, physicians who aren’t doing their own billing don’t know their uninsured patients received hospital discounts.

Dr. Jay Chauhan, an independent head and neck surgeon in the northwest suburbs, underscores why some of his peers might not be discounting as much, even for patients who can least afford to pay.

“I’m making about 25% of what I did on some of the surgeries that I performed when they first came out 25 years ago,” Chauhan said.

He has worked on his own, even answering phones at his practice, for 25 years, and laments how expensive it has become to be a physician with the red tape of regulations, increasing rent and reimbursement that doesn’t fully cover how much it costs to treat patients.

Chauhan said he plans to close his practice soon.

‘There are millions of people just like her’

A MacNeal spokeswoman declined to comment about Elma’s case. She did not respond when asked why MacNeal’s financial assistance policy doesn’t apply to all providers who treat patients. A senior director who worked with Elma to fully discount her care referred questions to another spokeswoman, who did not respond.

WBEZ reached out to the providers that continue to bill Elma to understand why they did not honor MacNeal’s rules about discounting medical care. Elma said she provided the same information about her finances to each independent provider that she gave to MacNeal and sent them the letter from the hospital showing her 100% discount.

One of them is North American Partners in Anesthesia, which describes itself as one of the leading single-specialty anesthesia and perioperative management companies in the U.S. Known as NAPA, the company says it serves nearly 3 million patients a year in more than 500 health care facilities around the country, including MacNeal.

Elma said NAPA billed her $6,170.55, then took about $1,000 off her bill.

After WBEZ inquired about Elma’s balance, she said NAPA discounted it further, to $1,500. A NAPA spokesman disputed the timing of the additional discount and said the company did so in March.

In an emailed statement, the NAPA spokesman said: “We fundamentally believe that our mission is to ‘Do right by the patient, and everything else will follow.’ NAPA has long recognized that access to quality healthcare is essential to all.”

He said last year NAPA provided more than $20 million in discounted care to uninsured and low-income patients, but he would not disclose how much of a loss that is to the company.

The other provider that continues to bill Elma is Suburban Metabolic Institute, a group of surgeons in the western suburbs. Two physicians there operated on Elma, according to her medical bill. They originally charged her nearly $1,400, then reduced the bill to just over $800, Elma said. She has paid more than $100 so far.

Terri, who manages the practice and would not give her last name, said MacNeal’s financial assistance policy doesn’t apply to Suburban Metabolic because the group is for-profit. Nonprofit hospitals get tax breaks and other government funding that help cover the gap when the hospitals discount bills for patients, Terri emphasized.

“We are not considered part of that pot of money,” she said. “We would not get compensation in any way for any services that we do because we’re not employed. We’re not funded by anyone.”

Terri echoed Chauhan’s frustrations about how expensive it is to run a practice. About a third of Suburban Metabolic’s patients are low-income with public Medicaid health insurance, which doesn’t pay doctors much for the care they provide. Private insurance companies sometimes do not reimburse the doctor’s group on time, if at all, while patients with or without insurance skip out on their bills, Terri went on.

She said Elma could give her a call to discuss reducing her bill further. But, she added, “there are millions of people just like her.”

There could be some more help on the horizon for the uninsured. Illinois lawmakers recently passed a bill that extends state health care benefits to low-income people who are at least 42 years old regardless of their immigration status. The bill awaits Democratic Gov. JB Pritzker’s signature.

Still, this program has tight income limits and could be out of reach for many. Individuals can’t make more than nearly $19,000 a year to qualify.

Contributing: Linda Lutton