Sweet new research suggests that newly forming planets may have a flattened shape similar to that of a popular British candy.

A team of researchers from the University of Central Lancashire (UCLan) in England used computer simulations to model the formation of planets in dense gas disks around young stars. Comparing these models with actual observations, they discovered that the young planets took shapes that defied expectations.

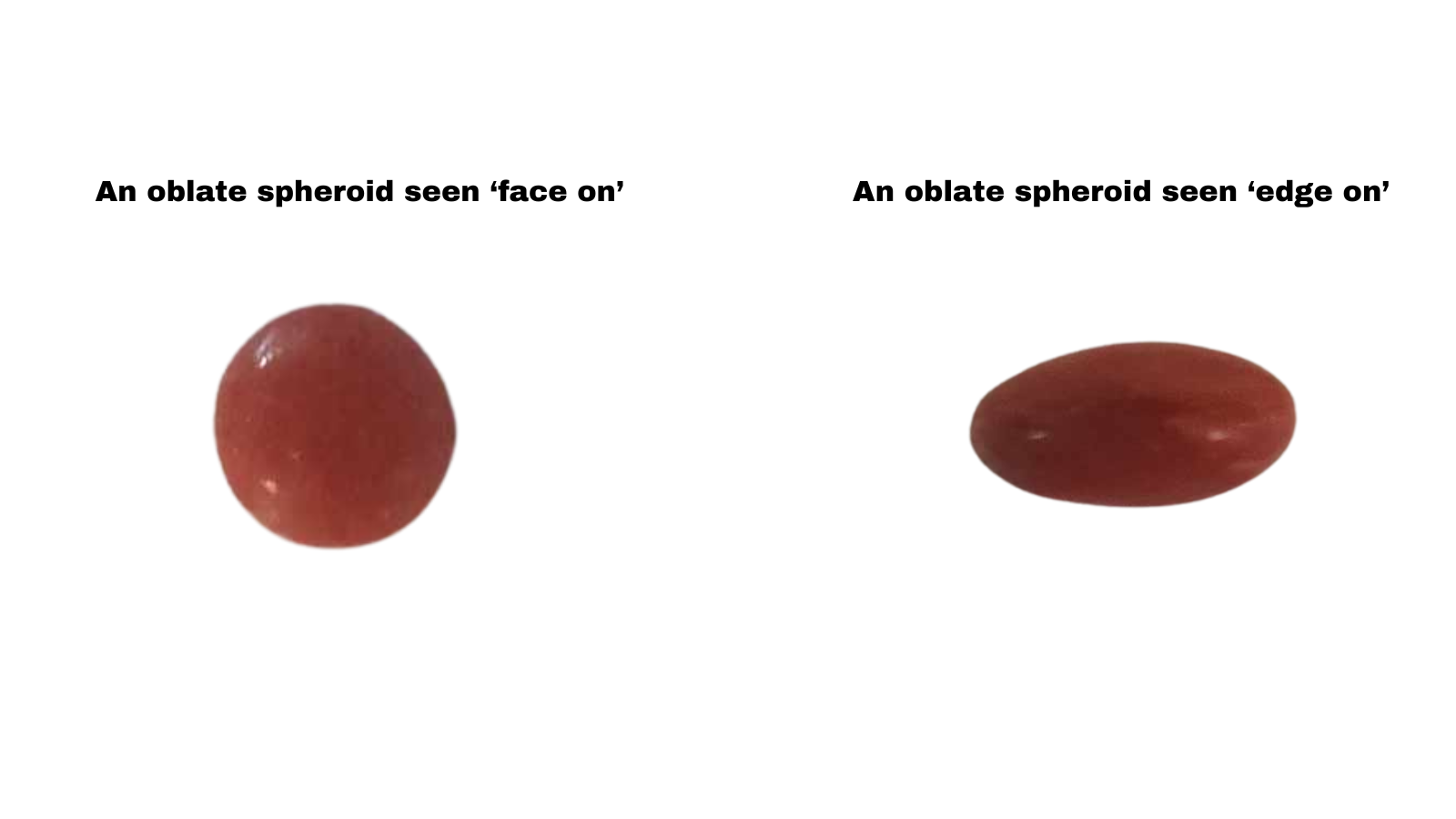

"We have been studying planet formation for a long time, but never before had we thought to check the shape of the planets as they form in the simulations. We had always assumed that they were spherical," said team member Dimitris Stamatellos, an astrophysicist at UCLan. "We were very surprised that they turned out to be oblate spheroids, pretty similar to Smarties!"

Readers outside the U.K. and Europe may not be familiar with Smarties — this version, at least. European Smarties are oblate spheroid-shaped disks of chocolate covered with a colorful hard candy shell that are manufactured by Nestle and sold in hexagonal cardboard tubes. (To readers in the U.S., Smarties are a different candy altogether: small, disc-shaped sugary wafers that come packaged in clear plastic wrapping.)

Related: James Webb Space Telescope detects clues about how Earth formed billions of years ago

While over 5,000 exoplanets have been discovered to date, astronomers still don't fully understand in detail the sequence of events that marks their birth and early evolution. The new research could shed more light on that process.

Planets build up from their (non-chocolately) centers

The UCLan team arrived at their cosmic-candy conclusion after examining the formation mechanisms of gas giant worlds like Jupiter. They focused on the initial shapes of such planets and how these could facilitate the growth of planetary seeds, resulting in massive planets even larger than our solar system's giants.

The standard theory of planet formation suggests that this growth happens gradually as dust particles stick together to form progressively larger and larger objects over long periods of time. This is referred to as "core accretion" and is the favored model of planet formation.

Alternatively, planet birth could happen over shorter timescales when large rotating protoplanetary discs around young stars break into pieces — the "disk instability" method. The team's model seems to lend more credibility to this less favored theory, supporting rapid planet formation via disk instability.

“This [disk instability] theory is appealing due to the fact that large planets can form very quickly at large distances from their host star, explaining some exoplanet observations," said UCLan's Adam Fenton.

The team's model suggested that newly forming planets take the shape of oblate spheroids because, as material falls onto them, it goes mainly to their poles.

One major conclusion from the research is that the appearance of young exoplanets seen from Earth may vary depending on how those planets are angled.

If Earth is directed "face on" to an exoplanet, then the planet will appear to have a traditional round shape; when seen on edge, however, a young planet would show its true Smartie-like shape and thus confirm if the team's model is right.

Observations of young planets, often still shrouded in gas and dust, have only recently become possible with telescopes such as the Atacama Large Millimetre Array (ALMA) and the Very Large Telescope (VLT). These observatories could provide evidence to bolster the Smarties theory.

The team will now continue to investigate the formation of planets using an improved computer model. They hope to discover the role the environment around a planet plays in influencing its formation and shape.

The team's research is available here. It has been accepted for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics Letters.