The allure of Europe’s capitals and major cities is undeniable. For decades, people have flocked to them to work in industry, set up businesses, and seek a better quality of life.

While the central, affluent neighbourhoods of Europe’s larger cities have always been pricey, areas once populated by working class households have now gentrified, becoming home to high income professionals and pricing out residents who cannot afford increased rents.

In some cities, this is compounded by residential properties being dedicated to tourist lets, as well as rising numbers of digital nomads – people who move around and work remotely, and are usually paid a much higher salary than the local average.

Leer más: Remote working: how a surge in digital nomads is pricing out local communities around the world

As a result, many cities have become unlivable for those who grew up in them. One clear example can be found in Portugal: the country’s monthly minimum wage is €820, but a 25m2 studio apartment in Lisbon can easily go for €700-800€ per month, with prices predicted to increase even more this year.

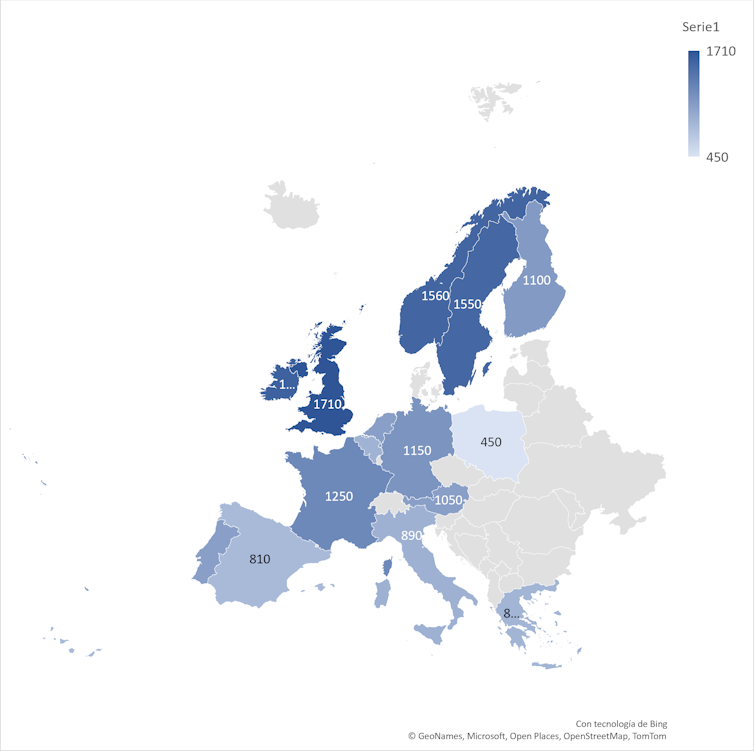

The situation is reflected across Europe. In nearly all countries, even a small one bedroom apartment is out of reach for low wage earners: on average, renting one would take 40% of their paycheck.

Foreign investment affects buying and rental prices

From 2010 to the second quarter of 2023, the EU witnessed a significant rise in property values, with housing prices surging by 46% and rents by 21%.

A closer analysis reveals that in the second quarter of 2023, compared to the same period in 2010, housing prices outpaced rent increases in 20 of the 27 EU member states. In all EU countries, as well as in the United Kingdom and Norway, purchase prices have risen since 2013 at rates well above inflation or wage increases.

Foreign investment plays a huge role in purchase prices. International investors – mostly from the US and Asia – regard European real estate as a secure and profitable investment, particularly in politically stable countries with robust economies. This external demand puts pressure on housing supply, thereby driving up property prices.

Rental markets are more strongly regulated, with measures like temporary or permanent rent caps in some areas making them less immediately vulnerable to the whims of foreign investment. Average rents have therefore increased more slowly, roughly corresponding to cumulative inflation over the same period.

However, a broad continental average masks skyrocketing rental prices in some areas. In the Spanish city of Valencia, for example, rent has shot up by 19.4% in the last year alone, with other cities such as Málaga and Barcelona showing increases of over 10% in the same period. Italy, France and, in particular, Ireland have also seen prices climb to unsustainable levels in recent years.

It is worth bearing in mind that purchase prices will eventually cause average rents to rise, as investors seeking a return on more expensive housing pass the cost on to renters. Many European countries have laws that prohibit rent increases within certain periods or under certain conditions, but these can only slow the process, and are often sidestepped through aggressive eviction tactics.

‘Touristification’ and other factors

One significant obstacle in addressing the housing crisis is that the factors influencing demographic and economic shifts vary widely between different regions and cities, as well as between different generations and income levels. This makes it hard for EU or even national legislation to pinpoint issues and provide definitive solutions.

In Spain, for example, the tourism industry has a significant impact on housing prices. At the end of 2023, the average housing price in 64 tourist towns and cities was €2,943/m², compared to €1,689/m² in non-tourist areas. Between the fourth quarter of 2014 and the fourth quarter of 2023, housing prices in Spain’s tourist cities rose by 61%, while the increase in other areas was 38%.

However, Europe’s housing crisis cannot solely be blamed on tourism – in some areas, the problem stems from a simple lack of new homes. In Dublin, young professionals struggle to find housing due to rising property prices and a shortage of affordable options.

In fact, many blame housing prices for Ireland’s current “brain drain” – an exodus of young, educated professionals leaving the country in search of better opportunities.

When it comes to purchase prices, increased financing costs such as mortgage rates and deposits present a further, serious challenge. While these are ultimately driven by central banks’ measures to mitigate rising inflation, they have a massive impact on housing affordability.

My research has predicted that larger inheritances will cause a long term decline in mortgage signings among Generation Z, but this is little comfort to those currently facing an uphill battle to even sign a mortgage, let alone pay one off.

Leer más: Generation Z may not need mortgages, here's why

Do we know when (or if) it might end?

Unfortunately, as long as the allure of European capitals remains strong the trend of rising property values is unlikely to reverse.

The magnetic attraction of metropolitan areas not only impacts house prices in cities themselves, but also in the regions where these cities are located, thus widening the economic divide with less dynamic areas. The surge in real estate prices may therefore lead to unequal wealth distribution in the long term, which will adversely affect employment and commerce in regions that lack a large urban centre.

In major cities like Paris, London, Madrid, and Brussels, as well as in countless medium sized cities, stagnant wages are pushing lifelong residents away from city centres, who in turn push other residents even further from the centre. This shift disproportionately affects young households – particularly first time buyers who find the market increasingly out of reach – and families struggling to find adequately sized homes to accommodate their needs.

The ongoing shift in real estate markets is altering the socioeconomic fabric of Europe’s cities dramatically, and it shows little sign of slowing.

Geoffrey Ditta no recibe salario, ni ejerce labores de consultoría, ni posee acciones, ni recibe financiación de ninguna compañía u organización que pueda obtener beneficio de este artículo, y ha declarado carecer de vínculos relevantes más allá del cargo académico citado.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.