Of all the civil rights policies enacted by U.S President Lyndon Johnson, affirmative action is arguably one of the most enduring – and most challenged.

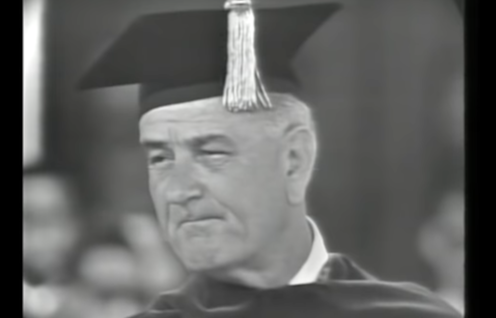

Johnson made it clear during a commencement address at Howard University on June 4, 1965, where he stood.

In his speech, “To Fulfill These Rights,” Johnson argued that civil rights were only as secure as society and the government were willing to make them.

“Nothing in any country touches us more profoundly, and nothing is more freighted with meaning for our own destiny than the revolution of the Negro American,” Johnson said.

In my view as a scholar of the history of affirmative action, Johnson’s speech and the legal structure it helped produce directly contradict those who would dismantle affirmative action and besmirch diversity programs today.

As the Supreme Court looks ready to strike down affirmative action in college admissions, it’s my belief that unlike the court’s conservative majority, Johnson understood that the U.S. could not serve as a moral leader around the world if it did not acknowledge its past of racial injustices and try to make amends.

‘Equality as a result’

Johnson knew that changing laws was only part of the solution to racial disparities and systemic racism.

“Freedom is not enough,” he declared. “You do not take a person who, for years, has been hobbled by chains and liberate him, bring him up to the starting line of a race and then say, ‘you are free to compete with all the others,’ and still justly believe that you have been completely fair.”

In proposing to address these injustices, Johnson laid out a phrase that would become a defense of affirmative action.

“We seek not just legal equity but human ability, not just equality as a right and a theory but equality as a fact and equality as a result.”

Achieving this latter goal, Johnson explained, would be the “more profound stage of the battle for civil rights.”

Johnson rejected the idea that individual merit was the sole basis for measuring equality.

“Ability is stretched or stunted by the family that you live with, and the neighborhood you live in – by the school you go to and the poverty or the richness of your surroundings,” Johnson said. “It is the product of a hundred unseen forces playing upon the little infant, the child, and finally the man.”

Johnson took a structural view of discrimination against Black Americans and explained that racial differences could not “be understood as isolated infirmities.”

“They are a seamless web,” Johnson said. “They cause each other. They result from each other. They reinforce each other.”

“Negro poverty is not white poverty,” Johnson said, “but rather the consequence of ancient brutality, past injustice and present prejudice.”

Johnson also rejected comparisons to other minorities who immigrated to the U.S. and had allegedly overcome discrimination through assimilation.

“They did not have the heritage of centuries to overcome,” Johnson said, “and they did not have a cultural tradition which had been twisted and battered by endless years of hatred and hopelessness, nor were they excluded – these others – because of race or color – a feeling whose dark intensity is matched by no other prejudice in our society.”

A constant challenge

That profound battle over how to address the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow and modern-day inequalities is once again before the Supreme Court.

Though the court is the most diverse in American history – with three justices of color and four women – the conservatives, who have historically opposed affirmative action programs, hold a 6-3 majority.

And that majority has the power to ban the use of race when the court issues a decision in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard and Students for Fair Admissions v. University of North Carolina. A decision is expected in June 2023.

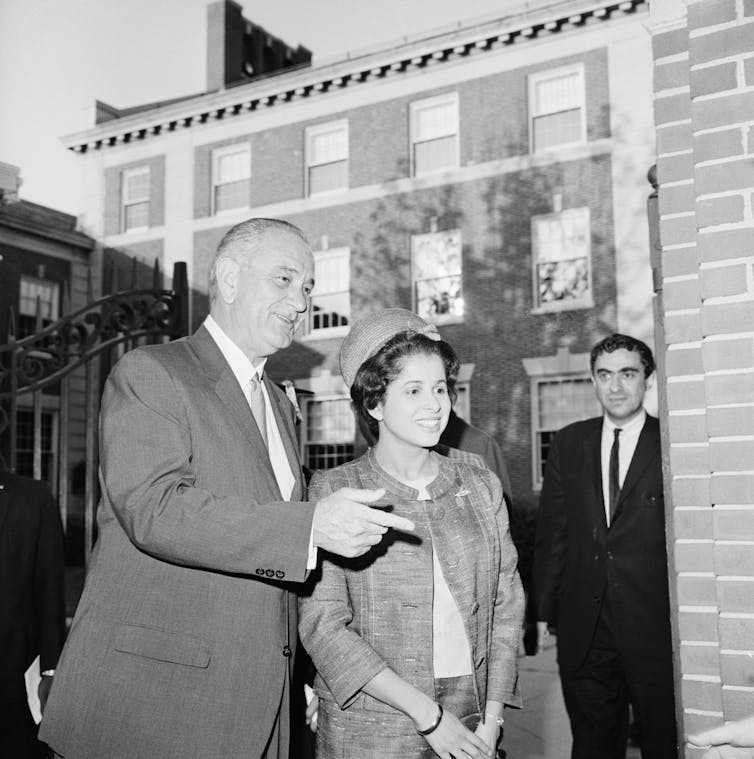

At the time of Johnson’s speech, the U.S. faced growing opposition to its escalating war in Vietnam and racial unrest across the country.

But Johnson was determined to achieve his goal of racial equality. During his commencement address, Johnson heralded the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act that he signed into law on July 2, 1964, and prohibited workplace discrimination. He also promised passage of the Voting Rights Act that would ban discriminatory voting practices. Johnson signed that into law on Aug. 6, 1965.

And shortly after his speech, Johnson signed Executive Order 11246 on Sept. 24, 1965.

It charged the Department of Labor with taking “affirmative action to ensure that applicants are employed … without regard to their race, color, religion, sex or national origin.”

For Johnson, racial justice was attainable and, once achieved, would alleviate social strife at home and advance the United States’ standing abroad.

Despite urging civil rights activists to “light that candle of understanding in the heart of all America,” even Johnson became disillusioned with the racial politics of forming a more perfect union.

In the aftermath of urban riots in Newark, New Jersey, Detroit and other U.S. cities in 1967, Johnson created the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders – better known as the Kerner Commission – to investigate the causes of the riots and suggest remedies.

The commission recommended billions of dollars’ worth of new government programs, including sweeping federal initiatives directed at improving educational and employment opportunities, public services and housing in Black urban neighborhoods.

The commission found that “white racism” was the basic cause of the racial unrest.

Although the report was a bestseller, Johnson found the conclusions politically untenable and distanced himself from the commission report.

Torn between his need to balance Southern votes and his ambition to leave a strong civil rights legacy, Johnson proceeded along a very cautious path.

He did nothing about the report.

U.S. Sen. Edward W. Brooke, Black Massachusetts Republican, was one of the 11 members on the commission.

In his book “Bridging the Divide,” Brooke explained Johnson’s reticence.

“In retrospect,” he wrote, “I can see that our report was too strong for him to take. It suggested that all his great achievements — his civil rights legislation, his antipoverty programs, Head Start, housing legislation, and all the rest of it – had been only a beginning. It asked him, in an election year, to endorse the idea that white America bore much of the responsibility for black rioting and rebellion.”

Even for a politician like Johnson, that proved too much to handle.

Travis Knoll does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.