The US Supreme Court is once again faced with the issue of racial gerrymandering as states wrestle with Republican-drawn congressional boundaries ahead of 2024 elections that could reshape control of Congress.

In the case of Alexander v South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, plaintiffs argue that the state’s legislature adopted a congressional map that discriminates against Black voters by moving hundreds of thousands of voters out of one of the state’s seven districts, while lowering the Black voting population in all but one of them.

A federal court already tossed out the map in January, finding that the state’s First Congressional District – currently represented by Republican US Rep Nancy Mace – violated the Constitution by using race as a determining factor when drawing its boundaries.

But during two hours of oral arguments on 11 October, the court’s conservatives appeared sceptical of the lower court’s decision, arguing that the evidence supporting it was merely “circumstantial” and that Republicans’ goals in drafting a map to benefit them were merely political, not racially driven.

“Disentangling race and politics in a situation like this is very, very difficult,” Chief Justice John Roberts said. “This would be breaking new ground in our voting rights jurisprudence.”

Conservative Justice Samuel Alito claimed there was “virtually no direct evidence” that would allow the plaintiffs to “disentangle race and politics” from their argument.

At the heart of the case is whether protections exist for Black voters in a state where one’s race and political affiliation are closely aligned, blurring the line between racial or partisan gerrymandering. An overwhelming majority of Black voters in the state vote Democratic. Only seven per cent vote Republican.

“That’s the whole point, isn’t it,” said liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor. “If you can’t reach a goal – no matter how laudatory it is – if the only way you can satisfy yourself, for whatever your political reasons are, is by using race, that’s illegal.”

Assistant US Solicitor General Caroline Flynn replied: “You can’t use race as a proxy for a political goal.”

“If you’re asking whether there is direct evidence that the legislature admitted in the 21st century that they sorted voters on the basis of race as a means to achieve their political goal,” said Leah Aden, an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund. “No, we do not have that.”

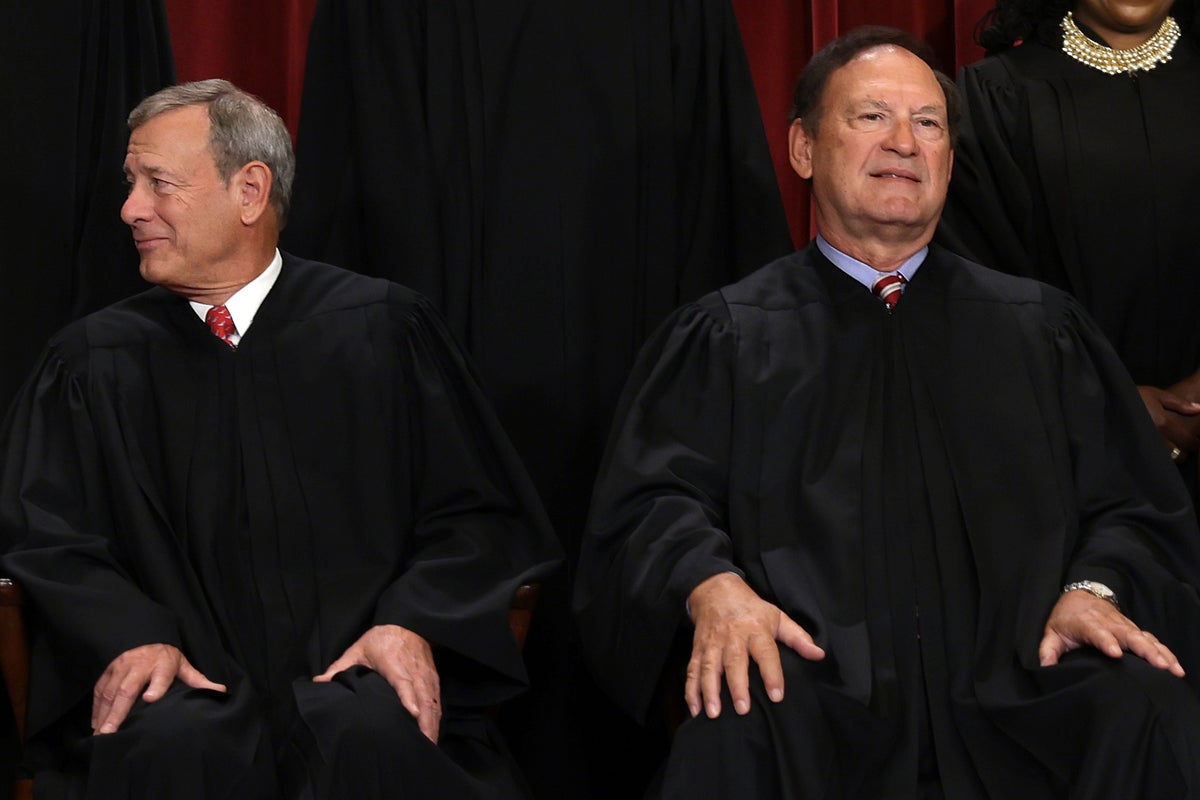

Chief Justice John Roberts, left, and associate Justice Samuel Alito, pictured in October 2022— (Getty Images)

Even after the map’s reshuffling, the state’s First Congressional District maintained the same Black voting age population of 17.8 per cent. How could Republican lawmakers not be thinking about race in that case, plaintiffs and the court’s liberal justices argued.

Liberal Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked whether they would need a “smoking gun”.

The move shaped the district into a Republican stronghold, with congresswoman Mace winning re-election by 14 percentage points last year.

South Carolina’s case is similar to the Alabama gerrymandering case before the court last year, which ultimately tossed a GOP-drawn congressional map and ordered a new one that preserved a Black majority district and added another with a Black voting age population of nearly 50 per cent.

While that case fell under the Voting Rights Act, the case in South Carolina hinges on the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

A federal court approved a proposal for Alabama’s new congressional map last week. That map, which will be in place through at least 2032, could also reduce the GOP’s attempts to hold its slim majority in the House in next year’s elections.

Similar legal battles over the future of other gerrymandered congressional districts are playing out in several states, including Florida, Georgia, Louisiana and Wisconsin.