Janina Scarlet’s origin story begins in Vinnytsia, Ukraine.

When the Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded on April 26, 1986, Scarlet was 3 years old. She and her family were exposed to radiation, and she spent much of her childhood in and out of hospitals. She still gets sick in response to changes in the weather and associates with Storm, the X-Men hero with the power to control the atmosphere.

All four of Scarlet’s grandparents were also Holocaust survivors, and she recalls growing up surrounded by evidence of the tragedy. “You couldn’t go anywhere in the city without there being some kind of a memory or a memorial for someone who was a survivor.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union, her family applied for refugee status and immigrated to the United States. It was there, at age 16, that she saw X-Men.

“I saw that we could use stories to help people process trauma.”

Like a lot of Millennials, seeing X-Men in theaters in the summer of 2000 was a formative moment for Scarlet. But most of us didn’t go on to invent a new form of therapy inspired by superhero movies.

“When I saw the first X-Men movie, I realized we could understand each other’s pain through fiction,” Scarlet says. “I could relate to Magneto because of his experience in surviving the Holocaust and his family not surviving. And then, seeing the X-Men being persecuted for being different, I could relate to that. I saw that we could use stories to help people process trauma.”

That realization spurred Scarlet to take her first psychology class, train as a clinical psychologist, and eventually develop Superhero Therapy, a practice that combines fictional characters with tried-and-true therapeutic frameworks like cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy.

“Fictional characters have become so representative of our real-life experiences,” she says. “Characters that are flawed and traumatized allow people to see not only that they’re not alone, but also that they belong.”

What is Superhero Therapy?

During her postdoctorate, Scarlet worked with active-duty Marines who had just returned from war — and noticed something familiar.

“Many of them would reference Superman or Batman,” she says. “Others would reference Star Wars or The Walking Dead or Game of Thrones. They were using these stories to share their own truth because it was too difficult to talk about what happened to them.”

For Scarlet, the reason was obvious. Where vocabulary can fail anyone trying to describe, first-hand, the experience of war, it’s easier to say that a horrific experience was “like a scene out of The Walking Dead. This realization — that a cultural reference can help a patient communicate, and even create a mutually understandable framework between patient and doctor — became the basis for Superhero Therapy.

In Scarlet’s program, superheroes and other pop culture characters become a starting point in determining what characteristics a patient wants to embody in life. She finds that it lessens the stigma around getting help, and appeals to people who “might otherwise be too nervous about being judged, and therefore might not seek therapy otherwise.”

Getting more granular in her book Super-Women: Superhero Therapy for Women Battling Anxiety, Depression, and Trauma, Scarlet offers a formula for becoming a superhero: “connection + safety.” Speaking to Inverse, she breaks down those two terms:

By “connection,” Scarlet means connecting to a greater purpose. “In order for us to be a hero, or our own version of a superhero, we need to connect to our greater sense of purpose, maybe our community,” she says.

This can only come after the patient finds safety. “We can’t do that if we don’t feel safe,” Scarlet says. “Emotional safety and, of course, physical safety is key to us being willing to engage.” As she explains to her patients, emotional safety comes from setting boundaries, practicing self-advocacy, and having “the courage and the support to continue building connections.”

Giving back to Ukraine

At a time when her home country is embroiled in war, Scarlet has put her skills to good use. She treats several Ukrainian refugees pro bono and consults with other providers who are offering aid for the crisis. She’s taught psychological first-aid training in free online sessions to more than 1,000 regular people interested in learning her methods.

Scarlet is also providing free training to Ukrainian psychologists on how to use Superhero Therapy to treat trauma. This includes the National Psychological Association Ukraine, which she’s partnered with to rehabilitate women and children who experienced the bombing of Kharkiv.

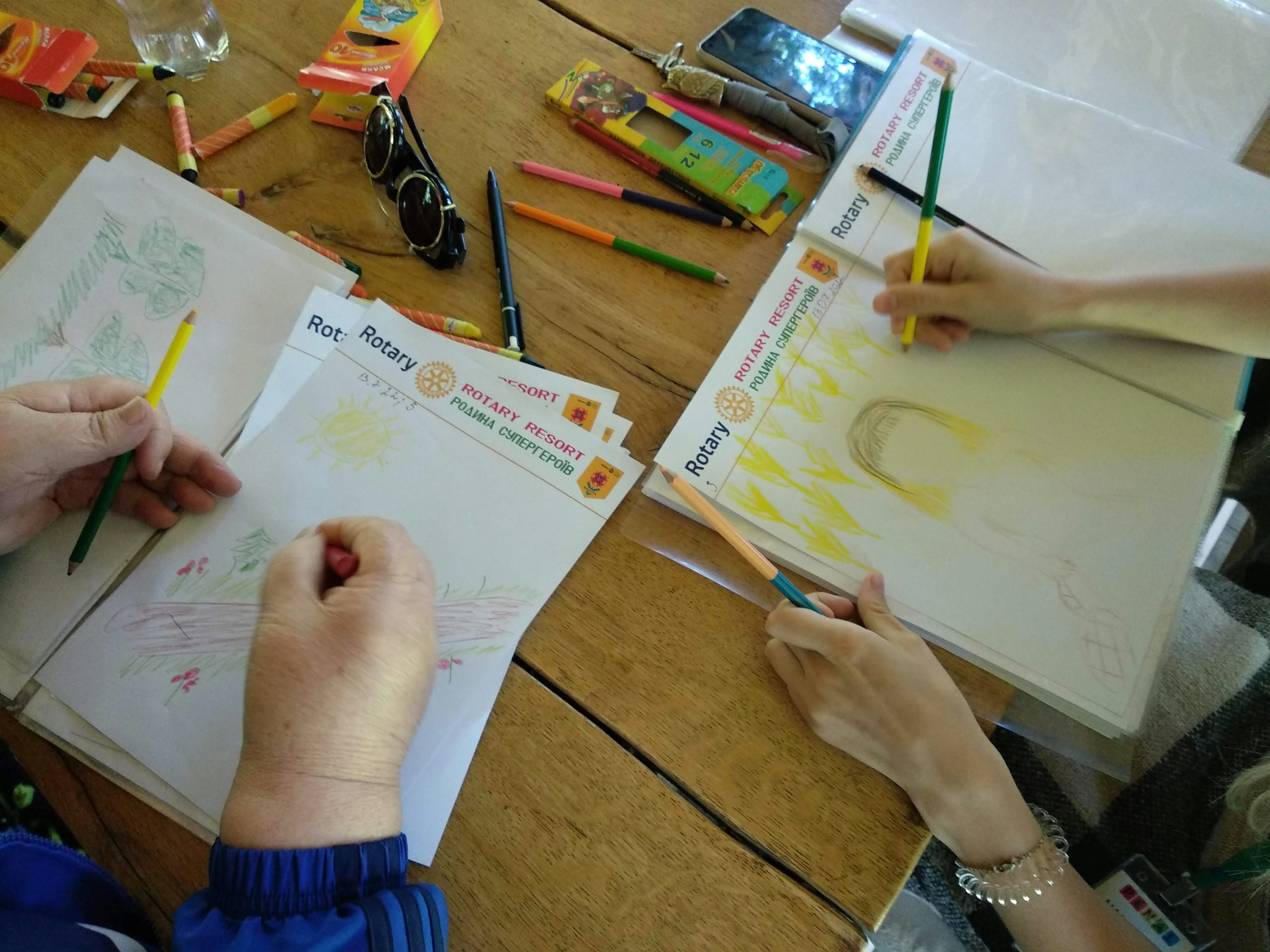

Olena Merliakova, an art and trauma psychotherapist and member of the association who participated in the training, says the experience gave her new tools to use with her own patients in the future. She helped organize a two-week event located in a safe zone within a Ukrainian forest.

“Every day our superheroes, mothers and their children, had separate tasks to strengthen their own resources,” Merliakova explains. At the end of the two weeks, the average level of anxiety among participants had decreased by half, while their level of stress resistance increased by 10 percent, according to the organization’s diagnosis.

“It’s about being ready to really be a superhero for yourself and your loved ones.”

For Merliakova, the success of the program was a direct result of the superhero connection.

“Everyone has had challenges in their own lives,” she says. “The idea of superheroes is not about the similarity of challenges. It’s about being ready to really be a superhero for yourself and your loved ones.”

The future of Superhero Therapy

Scarlet believes that Superhero Therapy can offer one more path to treating hard-to-reach patients at a time when mental health issues are on the rise. (According to Mental Health America, 15.08 percent of young Americans faced a “major depressive episode” in 2022, up 1.24 percent from 2021, while over half of adults in the U.S. with mental illnesses have not received treatment.)

Beyond being a tool to help verbalize difficult experiences, superheroes can also engender a sense of belonging, whether that means talking to a friend about Marvel movies or finding a community online to share your passion with.

“One of the top reasons for suicide is loneliness,” Scarlet says, “and therefore belonging is the biggest suicide preventer.”

She also points to research published in 2021 about the effects of playing video games on anxiety and depression during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“More people had turned to video games to manage their mental health to temporarily escape the horror of the pandemic,” Scarlet says, adding that video games may have literally been “life-saving” for some.

And while some may criticize Superhero Therapy for relying on fictional characters for emotional connection or even call disengaging from reality an unhealthy coping strategy, Scarlet disagrees.

“There’s nothing wrong with temporary escape if it means that we get a chance to unwind.”

The Inverse SUPERHERO ISSUE challenges the most dominant idea in our culture today.