Many forms of ear infections strike children and adults alike, but among the most common is acute otitis externa, also known as swimmer’s ear.

About 10% of Americans will experience swimmer’s ear during their lifetimes. Adults are affected more commonly, and children only rarely, generally ages 5 to 12.

But you don’t have to be swimming to get swimmer’s ear. Go out jogging or walking, or do yardwork on a hot day, and moisture from perspiration can drip in your ear. However, the occurrence increases fivefold in swimmers – thus the reason the condition came to be called “swimmer’s ear.” It also occurs more frequently in tropical climates because of humidity and higher temperatures.

As doctors who specialize in ear problems, we are actively involved in research and clinical treatment for children and adults struggling with ear, nose and throat problems. Practicing in the state of Florida, we’ve certainly seen our share of patients with swimmer’s ear.

Causes and symptoms of swimmer’s ear

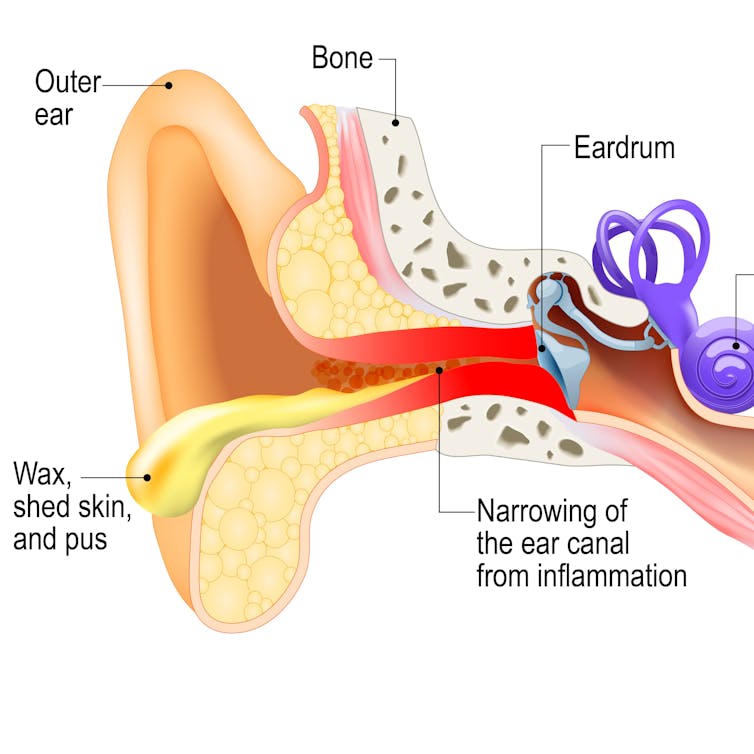

Swimmer’s ear is an infection in the external ear canal, the tube leading from the ear opening to the eardrum. Typically, swimmer’s ear occurs only in one ear, and sometimes the eardrum itself is affected. Moisture trapped in the canal leads to a break in the skin barrier and creates an opening for certain bacteria types to enter or existing ones to overgrow.

One of these culprits is the bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is present in soil and water throughout the world. These bacteria favor moist areas, such as sinks, toilets, inadequately chlorinated swimming pools and hot tubs, as well as outdated or inactivated antiseptic solutions.

If you have the infection, you’ll know it. Symptoms generally appear a few days after infection. The main symptom of swimmer’s ear is severe pain and discomfort. It’s particularly noticeable when the outer ear is tugged, or by touching the tragus – that’s the small bump at the front of your ear. Other symptoms include itchiness inside the ear, redness, swelling and drainage. A feeling of fullness, or the perception of a plugged ear, may also occur, along with disturbed balance and temporary hearing loss.

Predisposition to swimmer’s ear

Numerous factors can predispose someone to swimmer’s ear. They include a narrow ear canal, and skin diseases such as eczema or psoriasis. In addition, individuals wearing ear plugs, ear buds or hearing aids may be at an increased risk. Diabetics may also be more prone to the infection.

Swimmer’s ear can also come from something getting stuck inside the ear, excessive ear cleaning or contact with chemicals in hair dye or hairspray.

Diagnosis and treatment

Swimmer’s ear is diagnosed after a health care provider has gathered a thorough history and examined the inside of the ear. The ear canal will typically look red, swollen and moist. There is also a possibility of fluid drainage or the appearance of scaly, shedding skin. Depending on the degree of swelling, the eardrum may be hard to see. A sample of fluid may be removed from the ear and sent to a lab to look for bacteria or fungus.

Eardrops are commonly used to treat swimmer’s ear. These drops often contain antibiotics to kill the infection and steroids to stop the swelling.

One such eardrop is Ciprodex. It contains ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic, and dexamethasone, a powerful steroid. Patients will need to place about four to five drops in the infected ear canal twice a day for seven to 10 days.

Another commonly prescribed drop is Floxin, which contains an antibiotic but not a steroid. It is commonly prescribed in less swollen but still infected ears.

Other drop preparations include Cortisporin, which contains a commonly used combination of neomycin and polymyxin B, as well as hydrocortisone. However, neomycin is also damaging to the inner ear, so doctors nowadays often turn to Ciprodex or Floxin.

In some cases, the ear canal is too swollen for drops to reach the infected area, so the physician may place a wick or stent in the ear canal to keep it open. This will usually be left in place for three to five days until removed by the doctor, although occasionally the wick falls out once the swelling subsides. Usually, after 10 days the infection is resolved and the ear canal skin returns to normal.

Managing a persistent infection

Sometimes swimmer’s ear may not resolve after seven to 10 days of treatment with eardrops. Oral antibiotics are typically recommended if the infection has spread beyond the ear canal or in patients with poorly controlled diabetes. Hospitalization for swimmer’s ear is rarely necessary; however, complications that can occasionally lead to hospitalization include fever, worsening discharge, extensive narrowing of the ear canal or failure of previous treatments.

Among the precautions you can take to prevent swimmer’s ear: Keep the ear canal dry. Tip your head to one side to help the water drain. Use a soft towel or cloth, or gently use a hair dryer near it. If the self-cleansing mechanism of the ear canal is impaired, then the ear canal should be cleansed by a physician.

Since most bacteria prefer a pH-neutral environment, reducing the pH in the ear canal can prevent bacterial overgrowth. A homemade liquid tincture can be mixed from a solution of half rubbing alcohol and half distilled white vinegar. The alcohol combines with the water in the ear and then evaporates. This removes the water while the acidity of the vinegar keeps bacteria from growing.

Two to three drops are usually sufficient and can be applied as a preventive measure soon after the ear has been exposed to moisture. This liquid solution is not a replacement for medical treatment of an actual ear infection and is meant to be used only in people who are prone to such infections because of prolonged or frequent exposure to moisture.

Also, it is important to differentiate swimmer’s ear from a middle ear infection, the most frequent reason for the use of antibiotics in children under age 5. Middle ear infections are usually associated with a viral upper respiratory infection, and they are more often seen during fall and winter, when influenza and cold viruses are more prevalent.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.