A likely common ancestor of Indo-European languages, including English and Sanskrit, may have been spoken about 8,100 years ago, a new analysis suggests.

The research, according to scientists, including those from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany, represents a “significant breakthrough” in our understanding of the origins of Indo-European languages, which remained disputed for close to two centuries.

Until now, two main theories have tried to explain the origin of this family of languages, spoken currently by nearly half of the world’s population.

One is the Steppe hypothesis, which proposes an origin in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe around 6,000 years ago.

And the other is the “Anatolian” or “farming” hypothesis, suggesting an older origin tied to early agriculture around 9,000 years ago.

But previous analyses of Indo-European languages have come to conflicting conclusions about the age of the family partly due to some inaccuracies and inconsistencies in the datasets used.

To overcome these shortages, an international team of over 80 language specialists constructed a new dataset of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages, including 52 ancient or historical languages.

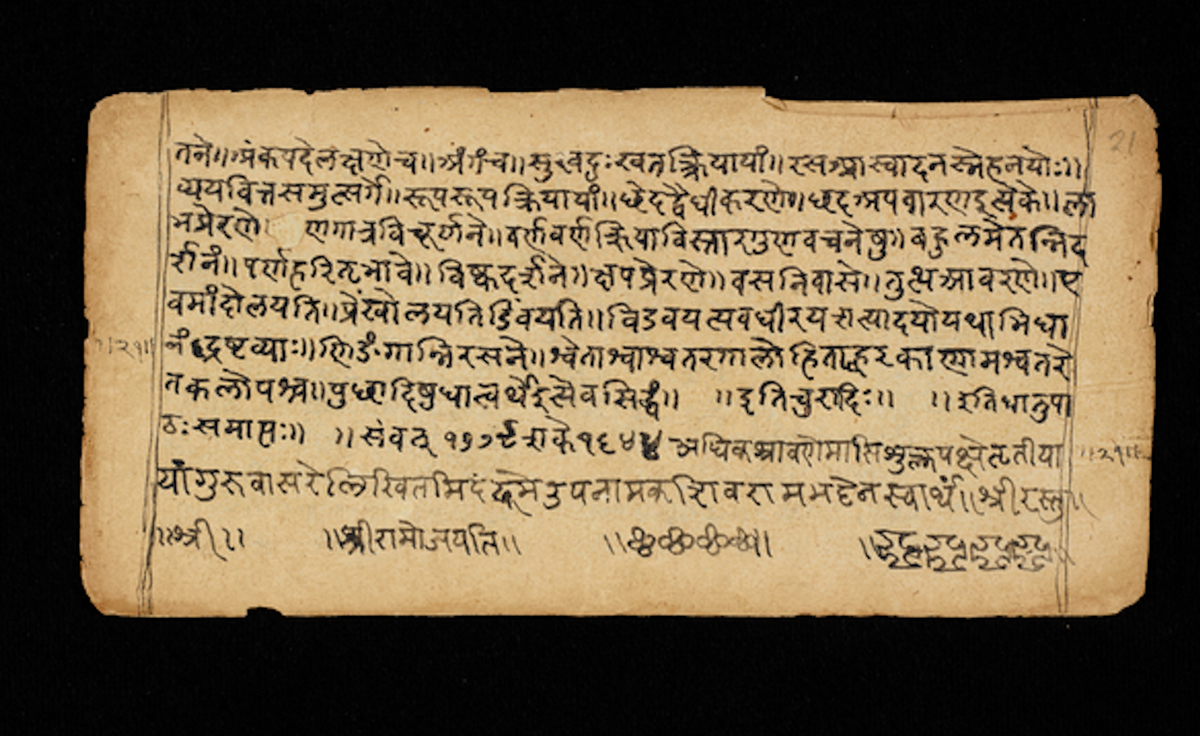

The new study, published in the journal Science, assessed whether ancient written languages, such as Classical Latin and Vedic Sanskrit, were the direct ancestors of modern Romance and Indic languages, respectively.

Scientists analysed the shared word origin among the core vocabulary among 100 modern languages and 51 non-modern languages.

The language family began to diverge from around 8100 years ago, out of a homeland immediately south of the Caucasus— (P. Heggarty et al., Science)

The research suggests the Indo-European language family is about 8,100 years old, with five main branches already split off by around 7,000 years ago.

“Our chronology is robust across a wide range of alternative phylogenetic models and sensitivity analyses,” study co-author Russell Gray said.

“Ancient DNA and language phylogenetics thus combine to suggest that the resolution to the 200-year-old Indo-European enigma lies in a hybrid of the farming and Steppe hypotheses,” Dr Gray said.

The latest research points to a new hybrid hypothesis for the origin of the Indo-European languages with a homeland south of the Caucasus and a subsequent branch northwards onto the Steppe, as a secondary homeland for some branches of Indo-European entering Europe with the later Yamnaya and Corded Ware-associated expansions.

“Recent ancient DNA data suggest that the Anatolian branch of Indo-European did not emerge from the Steppe, but from further south, in or near the northern arc of the Fertile Crescent—as the earliest source of the Indo-European family,” Paul Heggarty, another author of the study, said.

“Our language family tree topology, and our lineage split dates, point to other early branches that may also have spread directly from there, not through the Steppe,” Dr Heggarty said.