Jalen and his mom Savannah wanted a fresh start when they moved to Conroe for Jalen’s sophomore year of high school. Separated from a father who had been incarcerated, Jalen had struggled with depression, suicidal ideations, and ADHD.

But as one of few Black students, Jalen often felt “singled out.” —Black people make up 8 percent of Conroe High School students. He was censured for minor infractions such as wearing a hoodie or going to the bathroom during class time, while white classmates were not reprimanded for similar behavior. (Jalen, who is now 18 years old, is being identified by his middle name and his mother by her first name to protect their privacy.)

When his anxiety grew, Jalen’s mom asked the school for referrals for mental health services, which never materialized. His special education services, required under federal law for students with a disability, were never implemented.

Four months later, in April 2021, an altercation led to a student threatening to kill Jalen, and Jalen responded on Snapchat, writing, “The school would be shot up.” The other student then reported the message to school administrators without mentioning that he had threatened Jalen first.

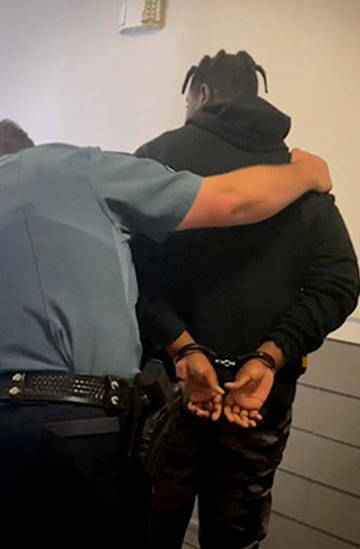

School district police found Jalen’s threat “not viable.” He lacked the means or access to firearms to carry out the action, and he had no documented history of violence against others. But Conroe Independent School District officials still had him arrested, expelled, and placed him in the juvenile justice system on probation for 177 days. Jalen said the other student, who is white, was never questioned or disciplined for threatening to kill him.

Less than four months later, Conroe ISD offered to end Jalen’s expulsion and reenroll him in the district, but only after lawyers at the advocacy organization Texas Appleseed pointed out that the district failed to conduct a threat assessment or provide mental health support as required by a 2019 school safety reform known as the threat assessment law.

After a school shooting killed eight students and two teachers at Santa Fe High School in 2018, the 86th Texas Legislature passed Senate Bill 11, which established provisions for a “Safe and Supportive School Program.” The law required all schools to implement an investigatory threat assessment protocol, as recommended since 2002 by federal agencies such as the U.S. Secret Service and the FBI.

Conroe ISD declined to comment about Jalen for this story. But in an email to Texas Appleseed that was reviewed by the Texas Observer, Conroe ISD insisted that the district did follow Texas law and conducted the threat assessment procedure, which requires a team of school officials, including a counselor, to investigate how the threat developed and offer appropriate mental health services to the student.

However, in what seems like an apparent violation of the law, Jalen and his mom say the district never offered Jalen any plan for mental health services. In a letter to the district, Texas Appleseed attorney Vicky Sullivan wrote: “Once the threat was deemed not viable, the school district took punitive action in expelling [Jalen] from the school district with no interest in providing remedial or mental health support.”

Conroe ISD is not the only school district that seems to be violating the 2019 school safety law. The Observer found that after three years, only 10 percent of school districts are fully implementing required threat assessment protocols and providing required counseling and referral programs to students of concern. While the state has shirked its responsibilities to enforce the law, some Texas lawmakers want to abandon the research-based practiceand instead expel students at “a single incident” of behavior that “interferes with the teacher’s ability to communicate effectively with students.” Ultimately, it’s kids who will pay the price.

The Texas Legislature tasked the Texas School Safety Center at Texas State University with training school districts on how to use the threat assessment model. Director Kathy Martinez-Prather said the law is meant to be preventative, not punitive. “We need to ensure that there are some appropriate interventions in place to get that student off a pathway to violence and have them be successful in an educational environment,” Prather said.

According to the law, all school districts must establish Safe and Supportive School Program (SSSP) teams to serve all campuses. Those teams must:

- Include diverse experts in behavior management, classroom teaching, counseling, emergency planning, law enforcement, mental health, and substance abuse, school administration, school safety and security, and special education.

- Receive training on how to conduct evidence-based threat assessments.

- Use a systematic approach to investigate and assess reports of “harmful, threatening, or violent behavior,” including verbal threats, threats of self-harm, bullying, cyberbullying, fighting, the use or possession of a weapon, sexual assault, sexual harassment, dating violence, stalking, or assault.

- Refer students who pose a safety risk for mental health support and issue appropriate disciplinary measures ranging from in-school suspensions, out-of-school suspension, or expulsion from the school.

- Report to the Texas Education Agency on actions taken by the SSSP team.

But what the Texas School Safety Center outlines in its “Model Policies and Procedures to Establish and Train on Threat Assessment”—a fact-based, multi-disciplinary approach to assessing school threats and providing students with mental health resources to prevent violence—is not happening in the vast majority of Texas schools, according to an Observer investigation.

The Observer compared all school districts’ 2021-22 responses to the Texas Education Agency’s Safe and Supportive Schools questionnaire with that year’s district discipline data.

We then assigned a compliance score—a grade—for each school district based on their adherence to the multiple provisions of the threat assessment law. We examined each district to see if it complied with four different elements of the law: Whether all campuses were served by an SSSP team, if teams were truly multidisciplinary, if team members received training, and whether the number of disciplinary records for bullying, fighting, assault, sexual assault, the threat or use of weapons, terroristic threats, or deadly conduct exceeded the number of threats that were assessed and addressed by districts’ SSSP teams. The districts with the highest compliance in all five categories were ranked highest.

What the Observer found was that only half of Texas school districts had SSSP teams that included members with the required areas of expertise. Only one-third of districts had trained all team members. Further, only 14 percent of districts reported conducting threat assessment and intervention procedures for all students disciplined for the concerning behaviors listed in the law.

Five percent of districts have no SSSP team whatsoever.

Many districts appear to have failed to provide threat assessments or services to youth before expelling them for actions considered unsafe, according to a related comparison of expulsions to school threat assessment statistics.

The Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District, the site of the shooting that killed 19 students and two teachers last spring, expelled 33 students at a rate of 7 out of 1000 students. The district did not report conducting any threat assessments or mental health interventions for any of those students.

In contrast, the Santa Fe Independent School District, which includes the high school that inspired the 2019 law, has conducted threat assessment protocols for all students of concern.

The Observer also found that some very large school districts, like Fort Worth and Beaumont Independent School Districts, had more than 700 relevant disciplinary actions and none were assessed by an SSSP team.

The law does not require all expulsions to be first reviewed through threat assessment protocols; for example, substance abuse actions are not required to be reviewed by an SSSP team. However, the high number of expulsions and low number of assessments in some districts indicate a focus on more punitive, rather than preventative, measures in dealing with student behavior.

The Observer shared its findings with Prather, director of the Texas School Safety Center, who expressed concern: “The idea behind a threat assessment team is that this shouldn't be something that the assistant principal is doing or just the law enforcement officer,” Prather said. “The threat assessment process is not meant to engage in exclusionary discipline practices or simply just law enforcement intervention. … There could be a student who is in crisis who needs some mental health support. And if you don't have that expertise at the table to provide that perspective, those things can get missed.”

The Houston Independent School District had the highest number of relevant disciplinary actions, about 2,700, but at most only 3 percent of these actions were assessed and addressed with mental health or other interventions, records show.

Our analysis also reveals that some smaller charter school districts had the highest rates of student expulsion actions that had never been assessed by an SSSP team. For example, the Academy of Accelerated Learning in Houston expelled students at a rate of 33 per 1,000 students and did not implement threat assessment or intervention protocols for any of those students. Inspired Vision Academy in Dallas expelled students at a rate of more than 11 per 1,000 students but conducted threat assessment protocols for none.

Last school year, the Conroe school district expelled more than 300 students but at most conducted threat assessment and interventions for half of the students expelled, records show.

During the same school year Jalen was expelled, Conroe ISD expelled 161 students but reported conducting threat assessments and providing intervention only 106 times. That suggests that at most 66 percent of students the district expelled underwent a threat assessment procedure and were referred for further mental health intervention and support.

By the time Conroe ISD offered to reenroll Jalen, he and his mom had moved far away from Conroe. “Jalen was just so scared; he didn’t even want to go out the door anymore,” Savannah said.

In a report released last month, Texas Appleseed found similar gaps in the implementation of the state law based on 2020-21 school year data. Texas Appleseed called on the state to enforce the threat assessment law, which includes no penalties for noncompliance. The Observer reached out to the Texas Education Agency for comment on how the agency plans to hold districts accountable, but the agency did not respond.

The advocacy organization Texas Appleseed is also demanding that the state provide more funding for threat assessment training, data collection, reporting, and the hiring of more counselors and mental health professionals.

In our independent analysis using more recent data, the Observer found that 40 percent of school districts did not have even one full-time counselor on every campus. Only a tenth of districts met the recommended 250 students to one counselor ratio.

A related problem is that many school officials and teachers seem unaware of school safety requirements. Only a third of Texas school districts have trained all staff on threat assessment protocols. A dozen teachers in various school districts interviewed for this story said they had never heard of the threat assessment law. Many reported that they feel left in the dark or they rely on social media or news coverage for information about reported threats in their district.

“Sometimes we hear there was a threat on social media. They tell us, ‘The school resource officer investigated. Everything is fine. No need to worry,’” said Sheena Salcido, who worked in the Ector County Independent School District for nine years. “And teachers are kind of told to just go about their day, not to let it affect us. Don't let students talk about it. Just move on.”

Jeff Daniels, Ector County ISD chief of police, told the Observer that the district arrested and criminally charged 39 students for making shooting threats last semester alone. The Midland-Reporter Telegram and local TV stations have reported that at least four of those students are in the fifth grade, and police investigations found that many of the students did not have the intent or access to firearms to carry out the threats.

When asked why his district was arresting so many young children, both Chief Communications Officer Mike Adkins and Police Chief Daniels claimed the district was just following the law. Both were not able to answer how many of these students received mental health services thereafter. Daniels said that Ector County ISD has a higher number of shooting threats because the district is making efforts to report them publicly.

While the Texas Education Code does require reporting these threats to law enforcement, it also allows schools to conduct a threat assessment process and says that “notification is not required … if the person reasonably believes that the activity does not constitute a criminal offense.” If a law enforcement officer is part of the threat assessment team, the referral to the team would fulfill the statutory notification. Further, the Texas School Safety Center calls on school districts to follow federal agencies’ guidelines, which state that threat assessment protocols must distinguish “whether a student poses a threat, not whether the student has made a threat.”

Daniels told the Observer that Ector County’s district policy mandates that any student who makes a school shooting threat, regardless of the threat assessment outcome, is assigned a three-day suspension, expelled from the classroom, and placed into an alternative education setting. Last school year, Ector County ISD expelled 190 students. Most expulsions were for vaping, which does not trigger a threat assessment, Daniel said. Only 5 percent of students who were disciplined for behaviors listed in the threat assessment law were assessed by an SSSP team and received interventions last year.

Such punitive measures have not prevented a spate of threats of school shooting that the Odessa community has reported this school year. State data shows that Ector County ISD has one school counselor for approximately 450 students, much more than the state-recommended ratio of 250 students to one counselor.

Salcido, who is also the vice president of the Ector County Texas State Teachers Association, attributes her district’s school safety issues to deepening wealth disparities between the expanding oil industry and working families in the Permian Basin. Housing prices have skyrocketed, and teachers are moving away. Without more funding, schools have become increasingly overcrowded and unsafe.

Salcido indicated that teachers wanted better options but in the same interview indicated she had never heard about the reporting and intervention process required by the state’s threat assessment law until being contacted by the Observer.

“Teachers don’t just want to get students in trouble. We want them in our classrooms. So we really need a better way of being able to communicate when we have concerns about students when they have violent or really aggressive behavior. … We want to be involved in the process and make sure that students are getting the support that they need,” Salcido said.

Andrew Hariston, director of the Education Justice Project at Texas Appleseed, said he believes that if the state improves the understanding and enforcement of SB 11’s threat assessment laws, school districts could practice “preventative, nonpunitive measures to facilitate the growth and the healing of young people and create learning environments where school shootings or acts of mass violence or threats will be a rarity because young people [would] feel nurtured and supported.”

Jalen and his mother elected to tell the story about his expulsion from Conroe ISD in the hope that it might help other students targeted for disciplinary action after they were struggling with mental health issues or with bullying. Ultimately, Jalen came out OK—no thanks to Conroe ISD. By the time Conroe ISD ended Jalen’s expulsion and offered to reenroll him in the district, Jalen had already graduated, finishing his GED in just five weeks. He is now working to save up money to attend community college.

“It was easier to focus on schoolwork when you're not in a hostile place. Or at least not in a place where you think people are out to get you, which is what I especially felt like there. Like I didn’t belong,” Jalen said.

More about Threat Assessment Teams

- The Texas School Safety Center offers a toolkit for understanding and implementing threat assessment procedures in schools.

- The U.S. Secret Service outlines in this guiding document factors to assess when conducting a threat assessment and how to promote a supportive school climate to reduce safety risks.

- If you believe your child’s rights under SB 11’s threat assessment law have been violated, you can reach out to the organization Texas Appleseed.

We would also like to hear from you! If you are concerned your school is not following the threat assessment law and would like to share your concerns, please reach out to me at lee@texasobserver.org or fill out this form.