Following a wave of pro-Palestinian protests led by students at universities across the country, a few schools, like Brown University, say they are considering divesting from companies that support or work in Israel.

In most circumstances, with summer on the horizon, the friction between protesting students and university administrations appears to have diminished, at least for the time being.

The dramatic scenes of police and state troopers dismantling student encampments on campuses and arresting protesters have sparked some accusations of heavy-handed law enforcement tactics. At the same time, some law enforcement agencies have said that extremist agitators who are not actually students contributed to the clashes on university campuses in April and May 2024. At least in the case of the Columbia University protests, about 29% of the people that New York police arrested were not affiliated with the school.

I am a former senior U.S. government counterterrorism official and scholar of national security and terrorism. The wave of recent pro-Palestinian, student-led protests reminds me of another tense era in the U.S. that was also prompted by U.S. engagement in a foreign war – the Vietnam War in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

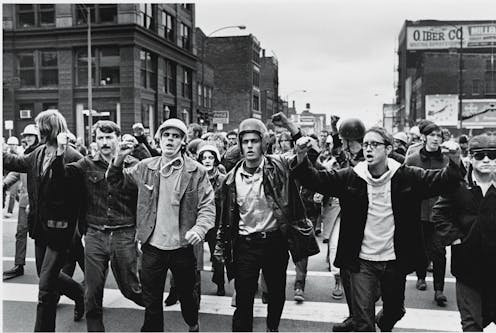

Students’ anger over the long-running U.S. war in Vietnam reached a boiling point on Aug. 28, 1968, at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. That’s when police and protesters violently clashed on the streets in what is known as “The Battle of Michigan Avenue.”

Student anger mounts over Vietnam war

The U.S. accelerated its support of the South Vietnamese government against communist North Vietnam fighters in the mid-1960s, shifting from military training to carrying out overt and direct U.S. combat operations. This happened after August 1964, when North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked U.S. destroyers in what is called the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

By spring 1965, the U.S. military was engaged in ground, air and naval operations against North Vietnam and their supporting Viet Cong insurgent fighters.

Anti-war protests in the U.S. also began around this time. A socialist group called Students for a Democratic Society, which opposed U.S. imperialism, played an active role within this anti-war movement that grew as U.S. military operations in Vietnam continued in 1966-68.

Meanwhile, President Lyndon Johnson announced in March 1968 he would not seek reelection and was halting U.S. bombing operations in Vietnam. This opened the door for Vice President Hubert Humphrey to run against Republican challenger Richard Nixon that summer.

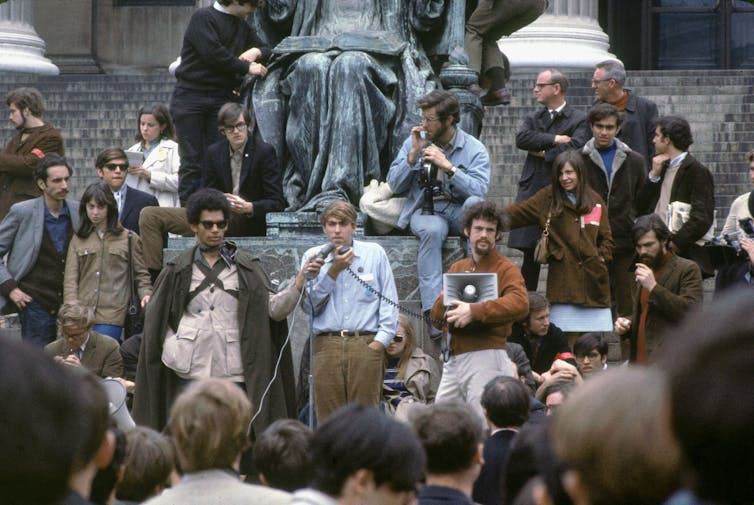

Various student groups and anti-war organizations, including members of Students for a Democratic Society, protested Humphrey outside the Democratic National Convention’s meeting in Chicago in late August 1968. They were angry that Humphrey did not strongly denounce U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Some protesters held signs that said, for example, “Imperialism Saigon Prague” and “Cease Fire Now.”

The protests turned violent late on the evening of Aug. 28, 1968. Chicago police, Illinois National Guardsmen and other law enforcement personnel beat protesters with batons and dragged and handcuffed them as they arrested about 600 people. According to one former Chicago Police Department officer involved in the events that night, multiple warnings were given for protesters to clear an area between Grant Park and the convention center hotel. When those instructions were not followed, according to this officer, the police began aggressively clearing out those who were still present.

Roughly 100 protesters and law enforcement officers were injured in the clashes. Observers also got caught up in the fighting. Police physically forced out CBS correspondent Dan Rather, for example, from the convention building while filming a live news segment.

‘Days of Rage’

After August 1968, anti-war groups felt increasingly disillusioned about the prospects for peace in Vietnam – as well as what they perceived as the U.S. government’s unchecked power to suppress free speech and protest activity.

By early 1969, a new group called the Weathermen emerged from Students for a Democratic Society. The Weathermen had a more aggressive and revolutionary worldview than many members of Students for a Democratic Society. The Weathermen believed that direct confrontation with the state was the only way to achieve their objectives of forcing the U.S. to end the war in Vietnam and starting a revolution in the U.S.

The Weathermen organized a three-day protest called “The Days of Rage” in downtown Chicago in October 1969 – in recognition of the bloody clashes a little more than a year earlier at the Chicago Democratic National Convention. Hundreds of Weathermen came prepared for physical fights, with chains, baseball bats and slingshots. The protesters fought sporadically with law enforcement and the Illinois National Guard over the next three days in various sections of downtown Chicago, destroying property and leading to the arrests of dozens of Weathermen.

‘A declaration of a state of war’

By May 1970, the U.S. remained engaged in the Vietnam War, further fueling the Weathermen’s anger over the conflict and other perceived examples of what they called “capitalist imperialism” abroad and domestic inequality at home. The Weathermen rebranded themselves the Weather Underground and issued “a declaration of a state of war” against the U.S. government. The core group of Weathermen who were most focused on violent action probably numbered only in the several dozens. There was a larger group of members around the country who believed in the organization’s ideals but not the most extreme practices.

This was the start of the Weather Underground’s nearly decadelong campaign of domestic terrorist violence, including 25 bombings of government buildings and other perceived symbols of U.S. imperialism and injustice. They bombed the U.S. Capitol in 1971, the Pentagon in 1972 and the State Department in 1975, in addition to attempted bank robberies.

During this terrorism campaign, the Weather Underground’s bombings injured several people and caused physical damage to various locations. During a 1981 bank robbery in Nanuet, New York, three law enforcement officers were killed during a shootout with Weather Underground members. During this time, the FBI worked closely with various state and law enforcement agencies to investigate the group and criminally prosecute various members.

As a result, by the mid-1980s, many of the Weather Underground’s founding members were arrested or serving time in jail – essentially putting an end to their terrorist actions.

Prospects for domestic extremism now

This summer, the Democratic National Convention will again be in Chicago. The parallels with previous events in Chicago, such as the Battle of Michigan Avenue in 1968 and the Days of Rage in 1969, are intriguing to consider – especially given the strong divisions in the country now over the Israel-Hamas war. There are also, of course, major differences, including the fact that students in the U.S. do not have a legitimate fear of being drafted – and there are not U.S. troops on the ground in Gaza.

The pro-Palestinian student protests at universities this year have been mostly peaceful and have not resembled anything at the scale or intensity of physical confrontation with law enforcement seen in Chicago in the late 1960s.

This is not to say that anger and despair over U.S. policy on Israel will dissipate any time soon, even if the physical signs of encampments and protests on university campuses are disappearing.

Terrorism scholars and experts like myself have spent decades trying to determine the precise set of variables and factors that drive individuals down the path of violent action in the name of political and ideological causes. The current environment in the U.S. over the war between Israel and Hamas has not yet mobilized people down that path. But as protesters said in 1968, “the whole world will be watching.”

Javed Ali does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.