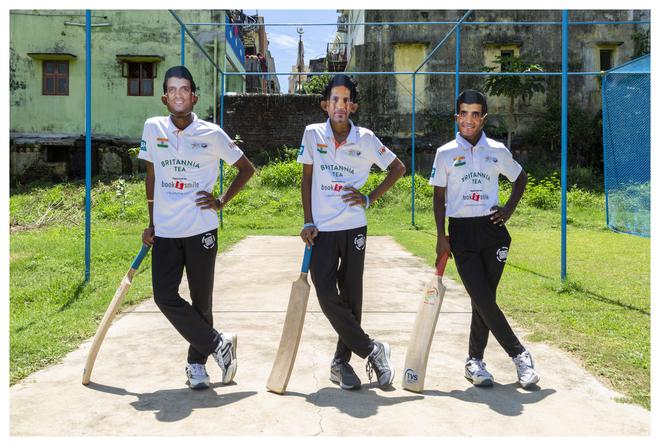

Sachin Tendulkar, Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid strike an effortless pose against a bright blue practice net wielding their weapon of choice, the bat. Look closer and you find that they are smaller in frame — children donning the masks of their favourite cricketers.

Another frame has a little girl masked as Smriti Mandhana standing in the centre of a railway coach crowded by other girls busy in preparation: some reading, some on the phone, and possibly strategising for their upcoming matches at the Street Child Cricket World Cup 2023 to which they are enroute.

The 2023 edition of this international tournament organised by The Street Child United in partnership with Shree Dayaa Foundation, held at the Amir Mahal cricket grounds, saw 170 children and 13 countries participating — a first in Chennai. It concluded on Saturday with Uganda as the reigning champions. But some sights from the tournament tell stories that reach beyond wins and losses. Rather, they speak of community, aspirations and pure, unfiltered grit.

The journey

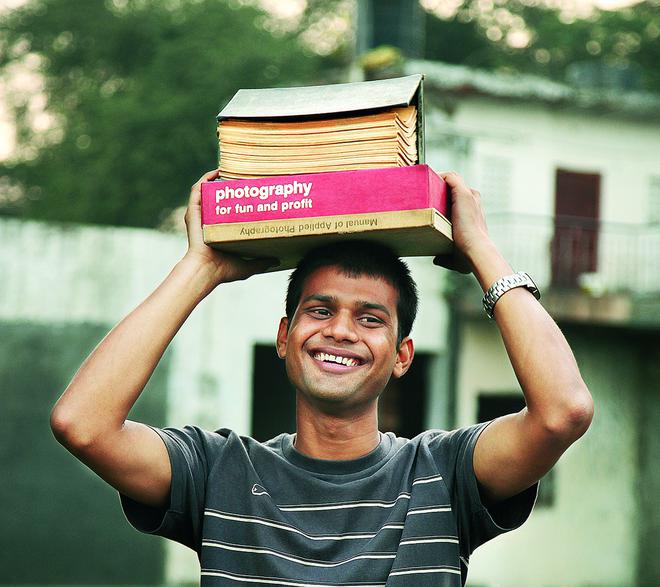

In the eyes of award-winning documentary photographer Vicky Roy, his subjects are the cricketing stars of the future. Their background should in no way, be a deterrent to dreams. To actualise this idea, all through the days of the world cup, he walked around the grounds carrying a silver bag filled with masks — of famous cricketing icons from around the world: his latest project. Vicky has been a part of Street Child World Cups since 2017, when Moscow hosted.

“I also come from the same background, and I know that despite the fact that these children come from different parts of the world, their stories are more or less the same,” says Vicky, against the backdrop of cheers by teams just about to pitch. As a boy, Vicky ran away from his home in West Bengal and started working as a rag picker at the New Delhi Railway Station. He was later rehabilitated by the Salaam Baalak Trust in Delhi. Many children participating in the tournament have similar trajectories in life, except each country has its own set of challenges including drug abuse, and domestic violence.

“They need a voice. And I believe that when I tell their stories, I am also able to change the viewers’ perception towards street children that they may meet again,” says Vicky, whose first solo exhibition Street Dreams (2018) documented children who shared his lived experiences. He was later picked by the US-based Maybach Foundation to document the reconstruction of the World Trade Center in New York. He undertook a course in documentary photography at the International Center for Photography, New York for the project. Despite traveling around the world, Vicky finds himself coming back to the subject he is most familiar with: India’s marginalised children.

Back in Chennai, Vicky could see how the tournament was able to build confidence among the participating children. “Sports give a kind of discipline to one’s life. Humanity is automatically built into it. They meet and become friends with children from other countries, which also cheers them up greatly.” The exposure, according to Vicky, contributes a lot to the children’s quality of life which will favour their drive to play professionally.

Innocente, one of the 14-year-old players from Burundi, agrees enthusiastically, “I have made a lot of Indian friends, and I am a big fan of Bollywood. It’s exciting. Both of us don’t know English, and we speak different languages but we communicate through gestures.” Most children cite their favourite memory in the city as the evening they spent at a waterpark, and the times they danced to traditional music from a fellow country.

Through these moments of jubilance, the pitch remains populated, pictures get clicked and masks remain intact. Cricket finds a way to be played.