British-ruled Tasmania's "foremost" naturalist was an untrained lawyer who traded stolen Aboriginal remains alongside Tasmanian tiger skins for scientific prestige, a new study reveals.

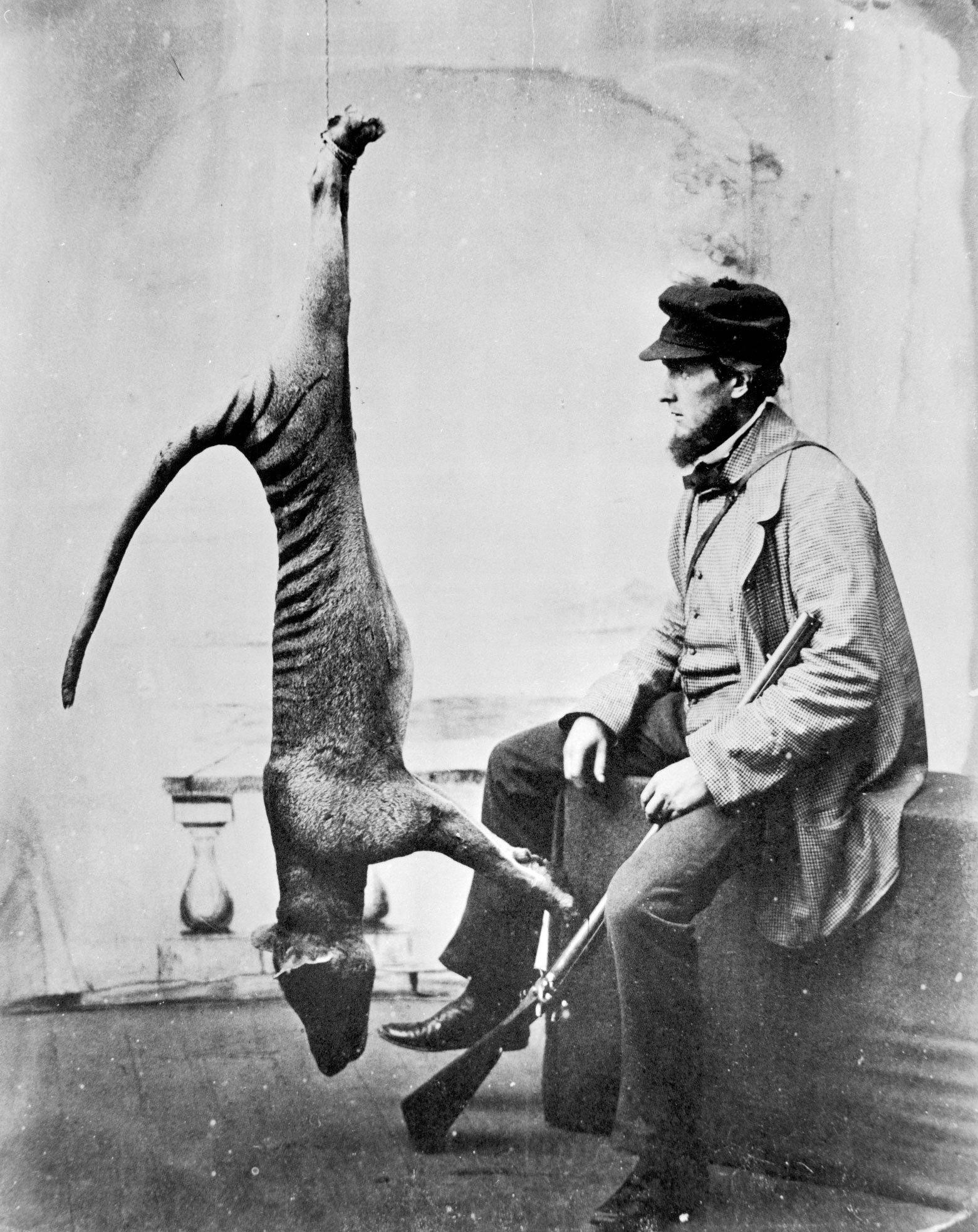

Morton Allport — an English-born 19th-century naturalist who lived in Tasmania's capital of Hobart — earned his scientific accolades by grave robbing human body parts and shipping them to European universities along with the remains of Tasmanian tigers, now-extinct marsupials also known as thylacines (Thylacinus cynocephalus).

Allport's activities, which include the mutilation of an Aboriginal man's corpse to gather evidence for pseudoscientific theories of white superiority, coincided with genocide against the island's Aboriginal peoples and the extermination of the Tasmanian tigers, which went extinct in 1936. The research, based on Allport’s archived letters unearthed at the State Library of Tasmania, was published Wednesday (Nov. 29) in the journal Archives of Natural History.

Related: RNA extracted from an extinct Tasmanian tiger for the 1st time

"We can now see that Allport sent more thylacine specimens to Europe than anyone else, and he also very proudly describes himself as the only person to be sending Tasmanian Aboriginal skeletons to European institutions," Jack Ashby, assistant director of the University Museum of Zoology at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science. "Effectively every skeleton of a Tasmanian person that reached Europe was sent by Allport."

When British colonists established the first European settlements in Tasmania (now a state in Australia) in 1803, the island's Indigenous Aboriginal population numbered between 5,000 and 10,000. Yet by 1876, after multiple successive campaigns of violence, murder and forced displacement (condoned and later outright sponsored through a bounty system by the British-controlled state), only the women kidnapped by the colonizers had survived, and many of them were tortured, pressed into forced labor and raped.

The systematic murder of Tasmania's Indigenous people, described by contemporary scholars as genocide, coincided with the hunting to extinction of the island's thylacines. The distinctively striped marsupial, once found across Australia but later endemic only to Tasmania, was hunted to extinction by British settlers who viewed the carnivore as a threat to their sheep farms.

As numbers of Indigenous peoples and thylacines dwindled across Tasmania, demand for "specimens" of both skyrocketed. By investigating Allport's correspondence, Ashby found that Allport had shipped a total of five Tasmanian Aboriginal skeletons and 20 thylacine pelts to Europe. Once there, the samples were studied by naturalists who were eager to make pseudoscientific observations of both the thylacines’ and the Aboriginal peoples' evolutionary "inferiority."

In return for his efforts, Allport was garlanded with scientific accolades and fellowships from universities across Europe.

"Thylacines were seen as pests in their own environment, and also described in similar ways to Aboriginal people as being 'primitive', 'stupid' and evolutionarily ill-adapted," Ashby said. "Both were effectively being blamed for what was happening to them — for the genocide and for their extinction — which exonerated the colonists from the fact that they were shooting them or rounding them up and taking them off island."

The most infamous instance of Allport's grave robbing occurred when William Lanne, incorrectly considered the last male Indigenous Tasmanian, died in 1869. Lanne was coveted as a prize specimen, and Allport entered into fierce competition with another colonist (the doctor William Crowther, who would later become the premier of Tasmania) to acquire Lanne's remains.

The result was a grotesque free-for-all: Crowther and his son snuck into the hospital morgue holding Lanne's body and cut off his head, swapping Lanne's skull with the skull of a dead white man.

Arriving later to the gory scene, Allport ordered Lanne's feet and hands to be removed so Crowther wouldn't be able to acquire a full skeleton. What was left of Lanne was buried the same day but was later found to have been dug up and stolen — most likely by Allport, who later admitted in a private letter that it was in his possession.

Lanne's skull has never been officially identified, but was likely brought to the U.K. by Crowther's son. Nearly all of the identified Tasmanian Aboriginal human remains Allport sent to museum collections have been repatriated and buried, aside from a skeleton taken from a grave on Flinders Island which remains in the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS).

Beyond highlighting the horrors of colonialism, Ashby said, his research shows that museum zoological collections are just as important for their social history as for their scientific data.

"Understanding why and how animals were collected, including the underlying political and social motivations, is key to understanding and addressing some of the social inequalities that exist today," Rebecca Kilner, director of Cambridge's University Museum of Zoology, said in a statement.