You may think “not another article on school funding”. But this important story has to be told and the book, Waiting For Gonski: how Australia failed its schools, should be read by every parent, economist and Australian committed to “the fair go”.

The title is apt and who would have thought a book on school funding would be a riveting read? Authors Tom Greenwell and Chris Bonnor have all the angles covered.

What went wrong?

The much-lauded Gonski reforms, recommended ten years ago, have not been effectively enacted. The book provides a clear account of how it all went wrong in “the Gonski we got” and “postmortem” analysis chapters.

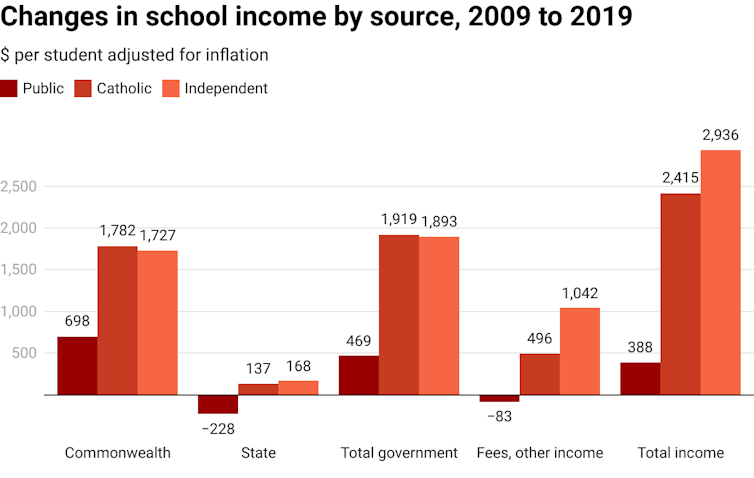

Rather than levelling the playing field, it is clear the system has become more unfair. More funding has gone to less needy schools. Government funding to non-government schools grew at five times the rate of funding for government schools over the past decade.

The review introduced the concept of the Schooling Resource Standard (SRS). The review panel said this was the funding “needed as the starting point for […] transparent, fair, financially sustainable and educationally effective” resourcing. The SRS uses a base funding amount each student, plus “loadings” for particular school and student needs.

The majority of government schools are yet to be fully funded to the SRS. At the same time, many non-government schools are overfunded, well beyond the standard (and fees sit on top of this government funding).

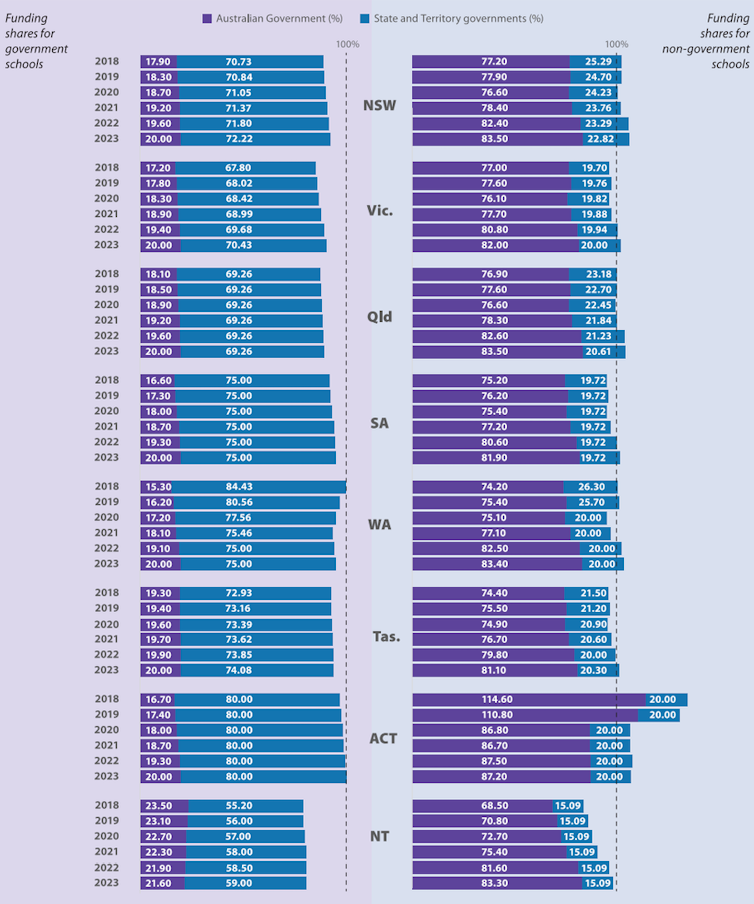

Shortfalls and excesses in SRS funding by state and territory, 2018-2023

A 2019 federal government review of needs-based funding makes it clear government schools’ needs are not being met and the system lacks transparency. New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania committed to reach 75% of SRS funding for government schools beyond 2023. NSW and Tasmania will reach 75% in 2027, Victoria in 2028 and Queensland in 2032.

A quote from the then Grattan Institute school program director, Peter Goss, is instructive:

“The federal government has locked in a model where every private school will get fully funded by 2023, whereas very few government schools will ever get fully funded. By 2030 we’re going to be having this same argument and it’s all predictable from now.”

Unlevel playing field has a long history

While many schools are still waiting to receive the Gonski needs-based funding, Greenwell and Bonnor make it clear there was also a sense of waiting in the lead-up to the review and 2011 report.

Pre-Gonski history provides important insights, including coverage of mistakes in the original establishment of Australia’s inclusive public education system. The system wasn’t really inclusive and created the first unlevel playing field, with well-resourced free education for most, alongside struggling Catholic schools. This changed after the 1960s, when the private sector successfully lobbied for funding. But, as the authors point out, “one unlevel playing field replaced another”.

The 1973 Karmel report followed, but was criticised because, as Simon Marginson wrote in 1984:

“[The report] did not develop an understanding of the dynamics of the dual system of schooling that operates in Australia […] [and] failed to go to the roots of inequalities in schooling”.

Gonski also failed on this score

Bonnor and Greenwell point out this criticism also applies to the Gonski review. Rather than tackle the complexities of the public-private system, Gonski left untouched the issues of school fees and very different school sector obligations, operations and accountabilities. Inequities in school operations, including enrolment policies, were not addressed.

While recommending adequate funding for schools where students had greater needs, the review did not question or seek to resolve why these students concentrated within disadvantaged schools, most of them government schools. The segregation of schools has since increased. Both the OECD and UNICEF have identified this as a key weakness in Australian schooling.

Greenwell and Bonnor point to the significance of the review’s focus on the impact of peers on student achievement, in a structure where fees sort and segregate students into different schools on the basis of socio-educational advantage. Bonnor says:

“The review panel couldn’t, or chose not to, join the dots between this phenomenon and Australia’s increasingly mediocre levels of student achievement.”

Gonski review panel member Ken Boston now agrees and attributes much of our educational woes to weaknesses in the report and failures of implementation. Noting the model was to be needs-based and sector-blind, he says: “Quite the opposite has occurred”.

Waiting for Gonski is a riveting, but depressing, account of how that happened. Drawing on interviews with key figures, the authors describe the manoeuvrings to get the funding legislation passed, the distorting of Gonski’s recommendations, the intensity of the activities of the lobby groups, and the eventual sabotage of the remnants of Gonski that managed to get over the line.

Students – and Australia – continue to miss out

The story is complete with a coming-of-age personal drama highlighting the impacts of funding on two young students as they move through their schooling.

It is important to remember that many thousands of children have completed all their schooling in the post-Gonski era, without the funding deemed necessary for the system to be “educationally effective”. The pathways of those lives have missed out on the educational enrichment funding to the Schooling Resource Standard would have brought.

Alongside Waiting for Gonski, a Why Money Does Matter conference marked the 10th anniversary with further sobering analysis, available here.

Gonski made “needs-based” equity funding part of our vocabulary but not part of our system. It is clear that action to fully implement true needs-based funding is urgently needed.

Waiting for Gonski ends with a call to action. For our education system to thrive nothing short of substantial structural change will do.

Greenwell and Bonnor also argue public funding brings public obligations, and a public contract is needed, requiring non-government schools to operate with policies comparable to those of government schools. Such an approach would “level the playing field”, which would undoubtedly strengthen Australian education and our economy. Do we have to wait much longer?

“Let us do something, while we have the chance! … Let us make the most of it, before it is too late!” ― Samuel Beckett, Waiting For Godot.

I previously published a report "Structural failure: Why Australia keeps falling short of its educational goals" co-authored by Chris Bonnor, one of the authors of 'Waiting for Gonski' I am also on the Board of the Centre for Public Education Research that hosted the conference mentioned in this article.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.