s it even a Stellan Skarsgård movie if no one is walking out of it in disgust? As much as the Swedish actor is recognised for his genial work in Thor, Good Will Hunting and Mamma Mia!, he’s mostly a shock magnet. Hover over his CV and you will find an array of projects awash with blood, viscera and full-frontal nudity. Many of his films have been welcomed with boos and boycotts, including his collaborations with Lars von Trier (six in total, including Breaking the Waves, Melancholia and Nymphomaniac), David Fincher’s sexually violent adaptation of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and now The Painted Bird, a harrowing portrait of child abuse that prompted people to leave the screening at three international film festivals.

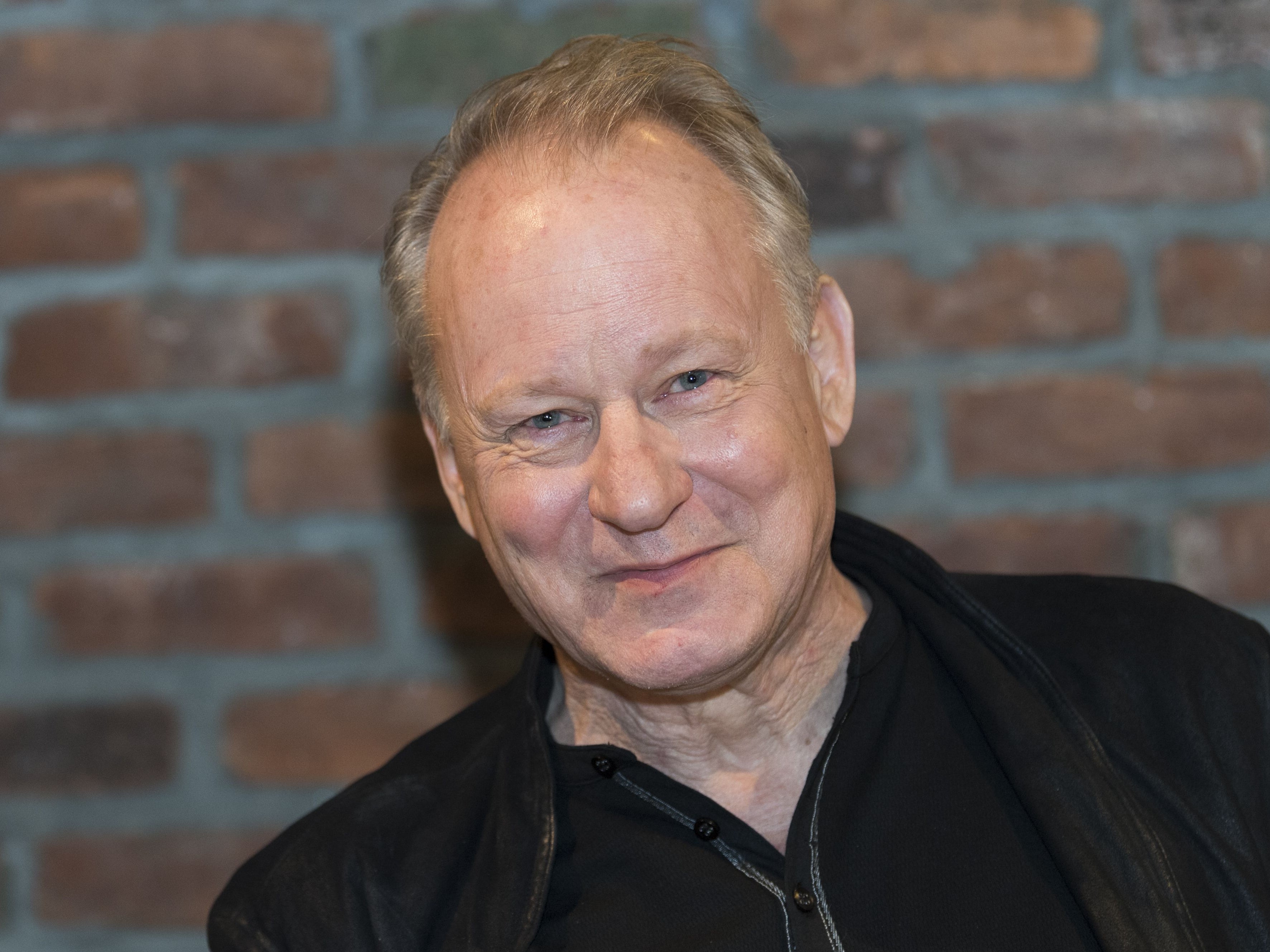

“I have no problem with depicting such horrors,” Skarsgård says over the phone from his home in Stockholm. “I like material that approaches dangerous borders.” He is a rascally conversationalist – 69 years old but bearing the cheekiness of someone’s naughty kid brother. He also wants to clarify something. Those reports of critics walking out of The Painted Bird? Totally exaggerated. “Some of them were just going to the toilet, I assure you.”

Still, you couldn’t blame them if they were fleeing in horror. The film is unforgiving in its depiction of a young boy (played by remarkable newcomer Petr Kotlar) who is wandering eastern Europe during the Second World War and encounters torture, sexual abuse and savagery. There is resilience and hope but it takes a long while to get there. Skarsgård provides a brief but impactful cameo as a German soldier left bereft amid the barbarism.

“I’ve made around 100 films, and it would be extremely boring and pedestrian if they all were mainstream and there was no edge to them,” he explains. “I also think that it is absolutely necessary to be controversial in the world. It is necessary to say things people don’t like all the time because we need the voices, we need the richness of ideas. They should be tested and disputed but they should be welcome.”

Skarsgård thinks British and American audiences have always had a warped understanding of sex and violence. “A Swedish journalist doesn’t ask me why I’m naked in films, or whether it’s embarrassing to show my dick,” he explains. “They’ve probably already seen it in the sauna.” He remembers howling at a review of Von Trier’s serial killer comedy The House That Jack Built a few years ago. “The critic complained that the violence was really unpleasant. It’s absurd – so we cannot show unpleasant violence, we can only show pleasant violence? That’s a horrible irony. If we’re making a Holocaust film, we should only show some pleasant ways of murdering Jews?”

“The Painted Bird is much less violent than most American popcorn films,” he continues. “The only thing is that the violence [here] is true, and it’s inflicted upon someone you feel you know. It’s not 200 stormtroopers that nobody cares about being mowed down.”

It’s a fair point, but then how does Skarsgård square his own Hollywood work? Films in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, in which he plays astrophysicist Erik Selvig, have famously levelled entire cities with little consequence, let alone killed off half their casts in a literal finger snap. He chuckles, as if he’s been trapped. “Morally, you must say that I am unfortunately a little flexible,” he jokes. “It’s not as bad when it comes to films that are so obviously fantasy. I do have problems sometimes with depictions of violence. Crime films today are about finding the killer, shooting him to pieces, blowing up everybody around him and then killing him again if possible. Hollywood encourages vigilantism so much, and that’s sad. But if Thor and Loki fight? That’s fine by me.”

Skarsgård has been acting since he was 16. That was when he was cast in the action-adventure series Bombi Bitt and, in his own words, “became the most famous teenager in Sweden”. “It was like being a pop star,” he remembers of his poster boy days. “Screaming girls and all that s***.” Learning that Skarsgård was effectively the Swedish Robert Pattinson in his youth isn’t a total surprise when you glimpse any of his offspring – he is at the top of a dynasty of ludicrously good-looking children that includes actor sons Alexander (of Big Little Lies and True Blood), Bill (aka Pennywise of the It movies), and Gustaf (of the Netflix series Cursed). Like them, he managed to avoid going off the rails.

“When I suddenly got extremely famous, my life went on as usual,” he says. “My parents were not impressed by all the press and the fame and they kept me very grounded. I also learned that your public persona has a tendency to very quickly move away from who you are. If the gap between people’s perception of you and who you feel you are becomes too big, it can be really dangerous.”

He did rebel against it all, though. He says he became “extremely pretentious and picky” in his twenties, determined to only work on “artsy” projects. In 1989, while filming Good Evening, Mr Wallenberg, a biopic about a Swedish diplomat who rescued thousands of Hungarian Jews during the Second World War, Skarsgård had an epiphany. “We shot it in Budapest and there were still Jews living there,” he remembers. “And they came up and touched me and started crying. They knew I wasn’t actually Wallenberg, but they had met him or had been saved by him, and suddenly the idea of ‘art’ became very irrelevant. The only thing that became relevant was to be truthful to those people and their stories and their lives.”

In other words, he loosened up a bit. He would still be drawn to brusque, troubled souls (an alcoholic absentee father in 2000’s Aberdeen, the cynical government official turned whistleblower in last year’s Chernobyl, which won him a Golden Globe in January). But he also embraced rampant silliness. “I became more lighthearted after Wallenberg,” he says. “I started saying, well, it’s not that important, it’s just a film and it will entertain people so I should probably do it anyway.” There was Ronin (1998), King Arthur (2004) and the almighty Deep Blue Sea (1999), in which Saffron Burrows bred genetically enhanced super-sharks and LL Cool J hid from them in an oven.

“I had fun doing Deep Blue Sea!” Skarsgård laughs. “In fact I’ve had fun doing some really bad films. Mamma Mia! is so fluffy, like a French patisserie, and it was a great joy. I’m as proud of that as I am The Painted Bird. But there are more films that resemble Mamma Mia! than there are films that resemble The Painted Bird, and we need more Painted Birds.”

Only one feels particularly relevant to 2020. “It's not just the Covid plague that is a problem,” he says. “We have authoritarian leaders taking over with populist slogans, and democracy being threatened all over the world. And with that we should not forget the Second World War, and we should not forget how easy it is to get even good people to vote for the wrong people.”

“These are sad times,” he sighs. “But they will end, and eventually the sun will engulf the Earth anyway, so..." There is a bit too long a pause after he trails off, before he breaks into a laugh. Coming from a man so creatively drawn to the most depraved of human behaviours, perhaps that Melancholia-style annihilation is suddenly a comforting thought.

‘The Painted Bird’ is out now digitally and in cinemas nationwide