How does someone become a designer? It used to happen like this: design school to trade show to design studio to (for the lucky ones) having work picked-up by a manufacturer and thereby joining the cabal of known names within design. The pools we fished from as scouts, manufacturers, buyers and media were shallow. We could list ten design schools of pedigree, five ‘emerging talent’ sections at fairs, and a handful of braver manufacturers who acted as incubators; and together, we birthed the new generation of design talent into the industry. It was all very safe and chummy. Everyone wanted to be Philippe Starck.

Thank goodness the industry – if we can even call it that – is weirder now. It is certainly more wonderful for it. We might lament the chaos of the forces that govern our lives, but these same forces have introduced a rich sense of possibility in how design and designers don’t just emerge, but make a living. Technology has liberated manufacturing possibilities, communication and routes to market. The lack of state funding for design education is woeful, but it has driven privately funded initiatives and community enterprises to step in. The design industry was once a fairly impenetrable, top-down establishment. Today, it looks more like an energetic grassroots movement.

Against this backdrop, we have turned our annual focus on the next generation inside out. When we first dedicated an issue to emerging talent back in 2008, we tasked ourselves with creating a graduate directory, systematically assessing the portfolios of students as they left university and headed into professional practice. Today, our role is less as arbiters designating future hotshots, and more as godparents helping to inspire young talents by showing the multitudinous ways in which designers can make it. The industry is not structured. There is no ladder. One of our subjects guffawed when asked about a career highlight to date: ‘Sorry,’ she laughed: ‘to describe what I do as a career sounds so old-fashioned.’ Amen.

What follows is a portfolio of ten portraits that tell the human stories of individuals (and a couple of couples) who are forging their own paths within design. Initially, their work caught our attention, stopping us briefly in our tracks as we trawled or scrolled. On further investigation, we felt they each represented this wind of change of which we speak. They span five continents, and their mode of working is individual and personal. They are each at a stage in their practice where they have developed an independent voice and language, and importantly, they all make a living from what they do. We have described them as ascending stars because we feel confident not just in their talent, but in their dedication and ambition, too.

Only a few of our selected designers had a formal design education. Some studied art, architecture, photography, interior design. Others arrived at their current calling via other professions such as politics, set design and film. Few label themselves as designers, and most spend time discussing the need for breaking down the barriers between disciplines. Design in their hands is a tool for expressing values, improving predicaments and addressing systems more broadly. Every single one places great emphasis on craft.

We asked some of them about a dream client or commission, hoping that, where brands might be named, we could do a bit of match-making. More fool us. These people have their sights set on designing for public spaces and landscapes, cultural institutions and social improvement. Similarly, when asked about a highlight on their professional journey to date, the majority of responses were concerned with relationships forged, materials mastered, knowledge acquired; not the more quantifiable measures of success one might expect, such as prizes and awards. Salone del Mobile was mentioned only once in the course of our ten conversations. They see their paths to market outside the fairgrounds in exhibitions and group shows, selling through independent retailers and galleries, or directly to clients and collectors. Reassuringly, they are business minded and not just dreamers; it is refreshing to note that many value cultural and commercial engagement hand-in-hand.

For our portfolio story, we tasked our new friends to choose somewhere to have their portrait taken that was important to them. Our inboxes quickly filled up with an imaginative array of suggestions: a stone quarry, a metal fabricator, their dad’s boatyard. As the portraits emerged, it became evident these talents value their roots and networks as foundational aspects of their identity and momentum. The risk of a portrait series is that it slips into feeling grandiose and aloof, rather than revealing. It is testament not just to our photographers but their subjects too, that here we have a disarmingly intimate collection of character studies.

There is a palpable sense of gumption and optimism in the stories behind each of our profiles. These are courageous young people in a time of great flux making a living from design, and remaking the outmoded rules of the industry as they do it. ‘The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently,’ wrote the American anthropologist David Graeber, and we feel it captures the spirit of the times and the power of this portfolio keenly. They are not just stars ascending, they are guiding lights for those who follow in their wake.

Emerging designers to look out for in 2025

Alfred Lowe, Adelaide

Lowe is an Arrernte person from Snake Well, near Alice Springs, where he grew up before moving to Adelaide for university. His work now sits in private collections and public galleries and, last year, he was awarded the Shelley Simpson Ceramics Prize by the founder of Mud Australia.

Olorunfemi Adewuyi, Lagos

Adewuyi studied architecture at Covenant University in Nigeria and is an associate at Lagos-based design and architecture practice Studio Contra. In 2023, he founded OMI Collective with a mission to rescue declining crafts and integrate them into contemporary life, honouring traditional skills and vernacular expressions that might otherwise be subsumed in favour of a globalised design language. Adewuyi believes design has a social and democratic impetus.

Kodai Iwamoto, Tokyo

Iwamoto originally hails from the city of Kagoshima. He studied product design at Kobe University, before moving to Lausanne to do his MA in product design at ECAL. His work blends the design sensibility of his formal education with the hands-on skills of a craftsman and the restless curiosity of an artist. He exhibited at Salone Satellite in 2024.

Amelia Stevens, London

Stevens studied architecture at Cambridge, then worked as a set designer and writer before setting up her design practice in 2021. Her furniture and object series have a strict formality and material confidence that bely the glorious indulgence of their function and witty, subverted literary titles. Standout pieces include ‘The Architectural Completion of a Floor Bolster Cushion’ series and the stainless steel and glass standing ashtray from her ‘Species of Table and Other Pieces’ collection, named after Georges Perec’s seminal 1974 text Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. Stevens is quick to point out that she does not smoke.

Agnes Studio, Guatemala City

Estefania de Ros, who studied interior design, and Gustavo Quintana-Kennedy, who studied architecture, first met in 2010, before founding Agnes Studio in Guatemala City in 2017. ‘We started collaborating informally on interior projects for friends, just for fun,’ says Quintana-Kennedy. This has since turned into an ongoing research and anthropological project intent on bringing Guatemalan craft traditions into the realm of contemporary design.

Miranda Keyes, London

Keyes studied sculpture at Edinburgh College of Art, specialising in bronze. She did an Erasmus year in Berlin, then moved back to London, where she had grown up, and began working with glass, which she had dabbled in a little in Berlin. ‘I began experimenting and haven’t really stopped,’ she says.

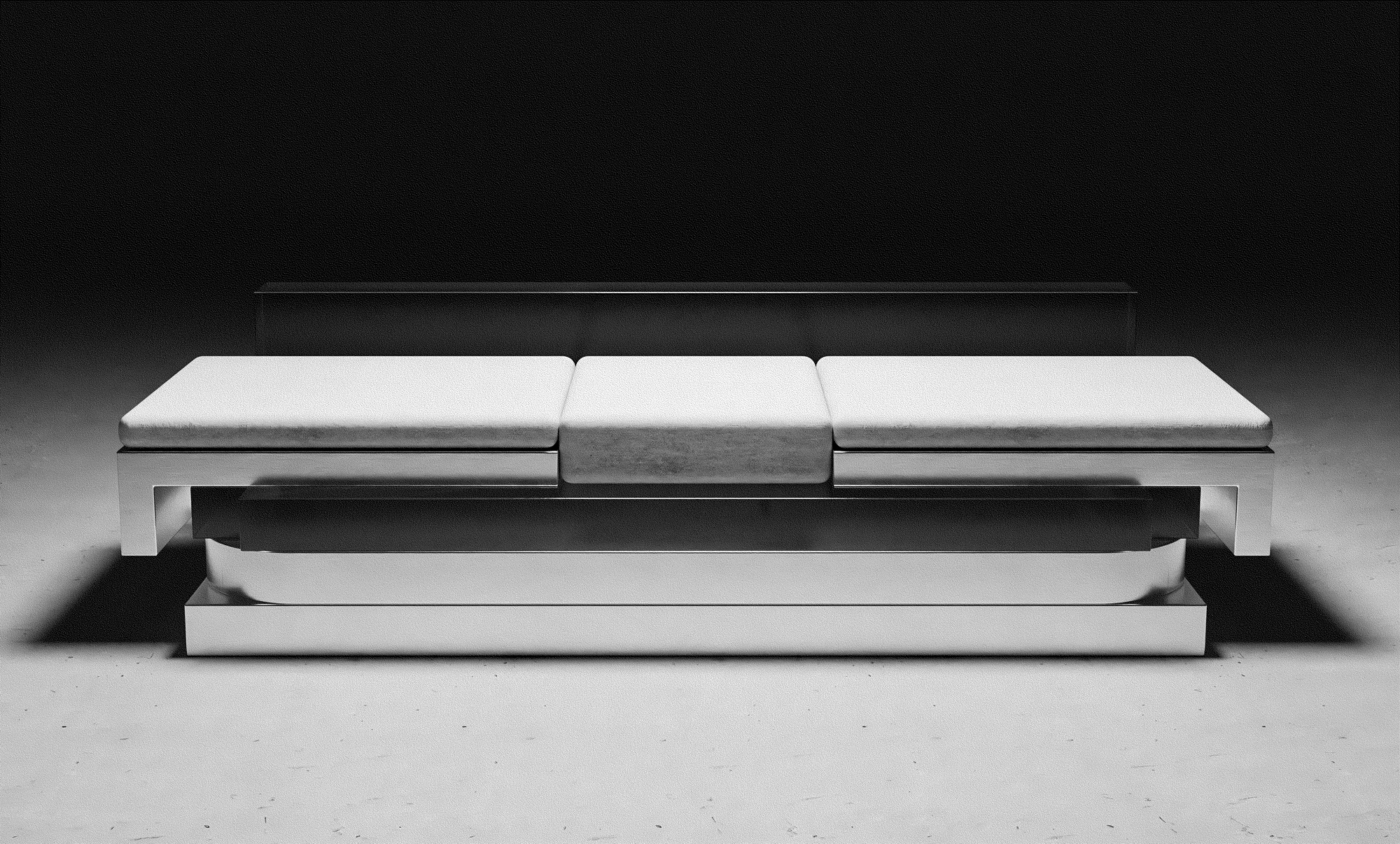

Federico Stefanovich, Mexico City

Stefanovich grew up in Mexico City with an industrial designer for a father and, after studying design himself, he spent a decade learning about furniture and product design in the studio of Hector Esrawe. In 2019, he exhibited work under his own name during Mexico Design Week, and last summer, he presented a full collection with Rudy Weissenberg and Rodman Primack’s AGO Projects.

Marc Sweeney, Loch Lomond

Sweeney studied art at the Glasgow School of Art, with a brief foray into film, before enrolling for an MA at the Instituto Marangoni in London. On graduating, he assisted Max Lamb, then returned to his Loch Lomond roots to make the most of the workshop facilities back home (his family runs Sweeney’s Cruise Company, which has been taking people out on the water since 1880). Sweeney sells his work directly and through Bard Scotland in Leith, Edinburgh.

Astraeus Clarke, New York

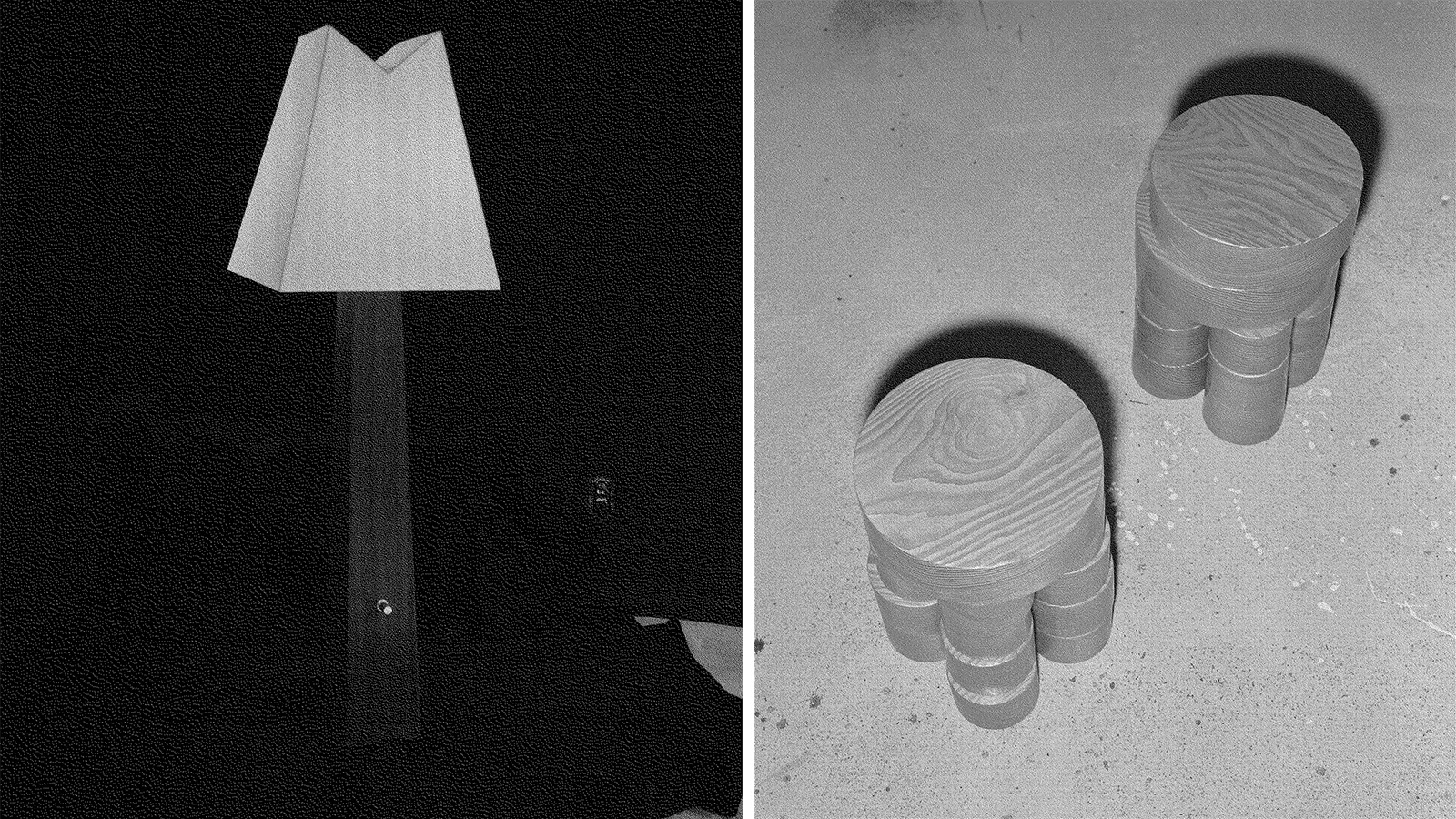

Chelsie and Jacob Starley are partners in life and business, both from Utah, now living in New York, where they launched their design studio Astraeus Clarke in 2022. The couple embarked on several careers before finding their feet. ‘We have so many failed businesses behind us,’ says Jacob. ‘From toys to swimsuits, we’ve learnt a lot about what not to do.’ Astraeus Clarke, by contrast, has seen rapid success. Known for their sculptural, characterful lighting, the duo are soon to embark on furniture and objects, too.

Pauline Leprince, Paris

Leprince came to design in a somewhat circuitous route via film and art direction, and there is a cinematic scope to her visual language. Her studio combines furniture and interior design, and she erupted on to the global stage last year with a staggeringly confident, avant-garde redesign of Karl Lagerfeld’s former apartment in Paris.