Pauline Kael was no fan of Stanley Kubrick’s movies. She deplored his “arctic spirit”. She compared A Clockwork Orange to the work of a Teutonic professor. In her review of 2001: A Space Odyssey, she wrote: “It’s a bad, bad sign when a movie director begins to think of himself as a mythmaker.”

I’m not a member of the Kubrick cult, but Kael’s animus always surprised me. After all, she’s the critic who wrote, in a dismissal of the 1986 Rob Reiner film Stand by Me, “If there’s any test that can be applied to movies, it’s that the good ones never make you feel virtuous.” A person who feels virtuous after watching a Kubrick movie should be prohibited from owning sharp tools.

David Mikics’s Stanley Kubrick: American Filmmaker is a cool, cerebral book about a cool, cerebral talent. This is not a full-dress biography – there have been several of Kubrick – but a brisk study of his films, with enough of the life tucked in to add context as well as brightness and bite.

Mikics is an English professor at the University of Houston and a columnist for Tablet magazine. His book is part of the Jewish Lives series of short biographies, which has given us (to name but two) Vivian Gornick on Emma Goldman and Robert Gottlieb on Sarah Bernhardt.

Kubrick (1928-99) was born in the Bronx to first-generation immigrant Jewish parents. His father was a doctor. The family lived on the Grand Concourse near a vast faux-baroque movie palace called Loew’s Paradise, with projected clouds that drifted across the ceiling. This became Kubrick’s second home. Like Binx Bolling in Walker Percy’s novel The Moviegoer, he was happy at a movie, even a bad movie.

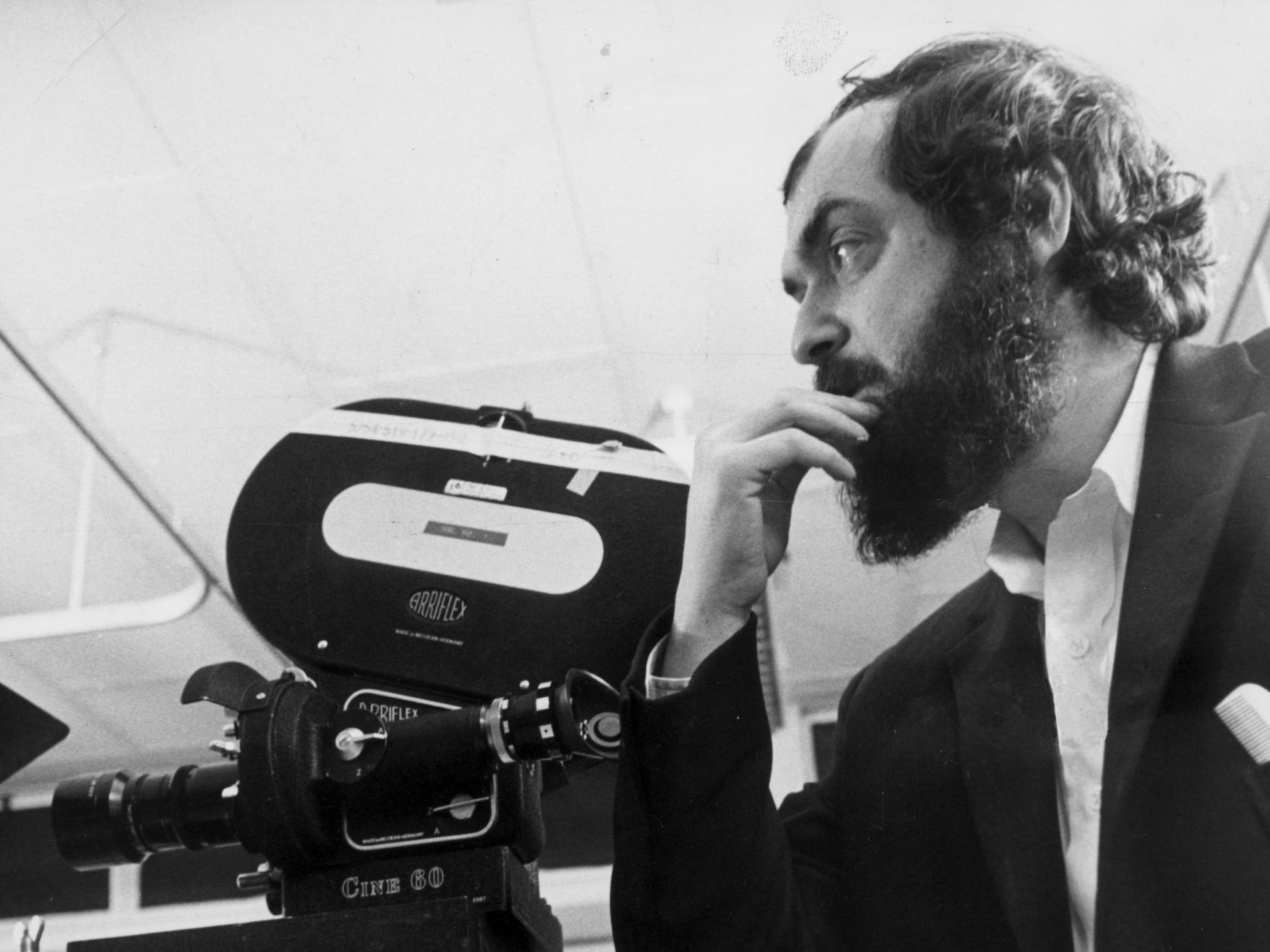

He was bright but a poor student. A natural malcontent, he resembled a grubby beatnik before there were grubby beatniks. Chess and photography were his things. Later, broke and in his twenties, he would survive by playing chess for quarters in Washington Square Park. Kubrick didn’t attend college. He married and became a photographer for Look magazine, a grittier alternative to Life.

Kubrick sat in on classes at Columbia University and got to know the Partisan Review crowd. There were few if any film schools then. He told an interviewer: “For a period of four or five years I saw every film made. I sat there and I thought, well, I don’t know a goddamn thing about movies, but I know I can make a better film than that.”

He borrowed money from his family to help finance his apprentice work as a director. He made two film noirs in the mid-1950s (Killer’s Kiss and The Killing) that attracted attention from critics. The movie that put him on the map as a mature talent was Paths of Glory (1957), a morally fraught World War I story starring Kirk Douglas.

The nine movies that followed are ones that anyone who cares about being alive in the public dark has seen, probably more than twice: Spartacus (1960); Lolita (1962); Dr Strangelove (1964); 2001 (1968); A Clockwork Orange (1971); Barry Lyndon (1975); The Shining (1980); Full Metal Jacket (1987); and Eyes Wide Shut, which was released shortly after his death in 1999.

Mikics is an adept student of Kubrick’s uncanny art. “His movies are about mastery that fails,” he writes. “Perfectly controlled schemes get botched through human error or freak accidents, or hijacked by masculine rage.” He unpeels the way that Kubrick’s movies, packed as they are with impieties, challenge, infuriate and entertain.

Writing about Tom Cruise’s awkward performance in Eyes Wide Shut, he reminds us what clicks about it: “Inner torment is never glamorous or sexy in a Kubrick movie. Instead it feels like a malfunction.” He notes that Kubrick, while dreaming up a possible cast many years before actually filming, considered Bill Murray for the role.

Mikics has a flair for nailing a performance. In a scene from Lolita, Sue Lyon is “a bratty virtuoso of gum-chewing, her eyes shooting darts of disdain”. Here he is on Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange: “He has killer style: jaunty and sharp in his Chaplinesque bowler, a buoyant boychik who will never realise how dumb he is.”

This book’s subtitle notwithstanding, Kubrick was in many ways the least American of American directors. He spent much of his adult life in the English countryside, an hour outside of London. He found it was cheaper to make movies there, and he hated to fly.

He stayed in touch with America. He liked gossip – “character analysis,” Elizabeth Hardwick called it – and was always on the telephone to Los Angeles. He had videotapes of pro football games sent to him. (He admired the editing of Michelob commercials.) He read The New York Times every morning. When bored during a movie, he was known to open a newspaper in a theatre.

This book captures his control-freak side. It also captures why people wanted to work with him. He had a feel for every aspect of what made a film work.

His voracious reading served him well. “I literally go into bookstores, close my eyes and take things off the shelf,” he told one interviewer. “If I don’t like the book after a bit, I don’t finish it. But I like to be surprised.”

His movies may lower the temperature in a room, but Mikics pushes back against the notion that frosty is all they are. Kubrick created some of the most indelible images in cinema. Mikics quotes the music critic Alex Ross, who wrote about Kubrick’s movies: “They make me happy, they make me laugh,” Ross said. “If this was cold, then so was Fred Astaire.”

© The New York Times