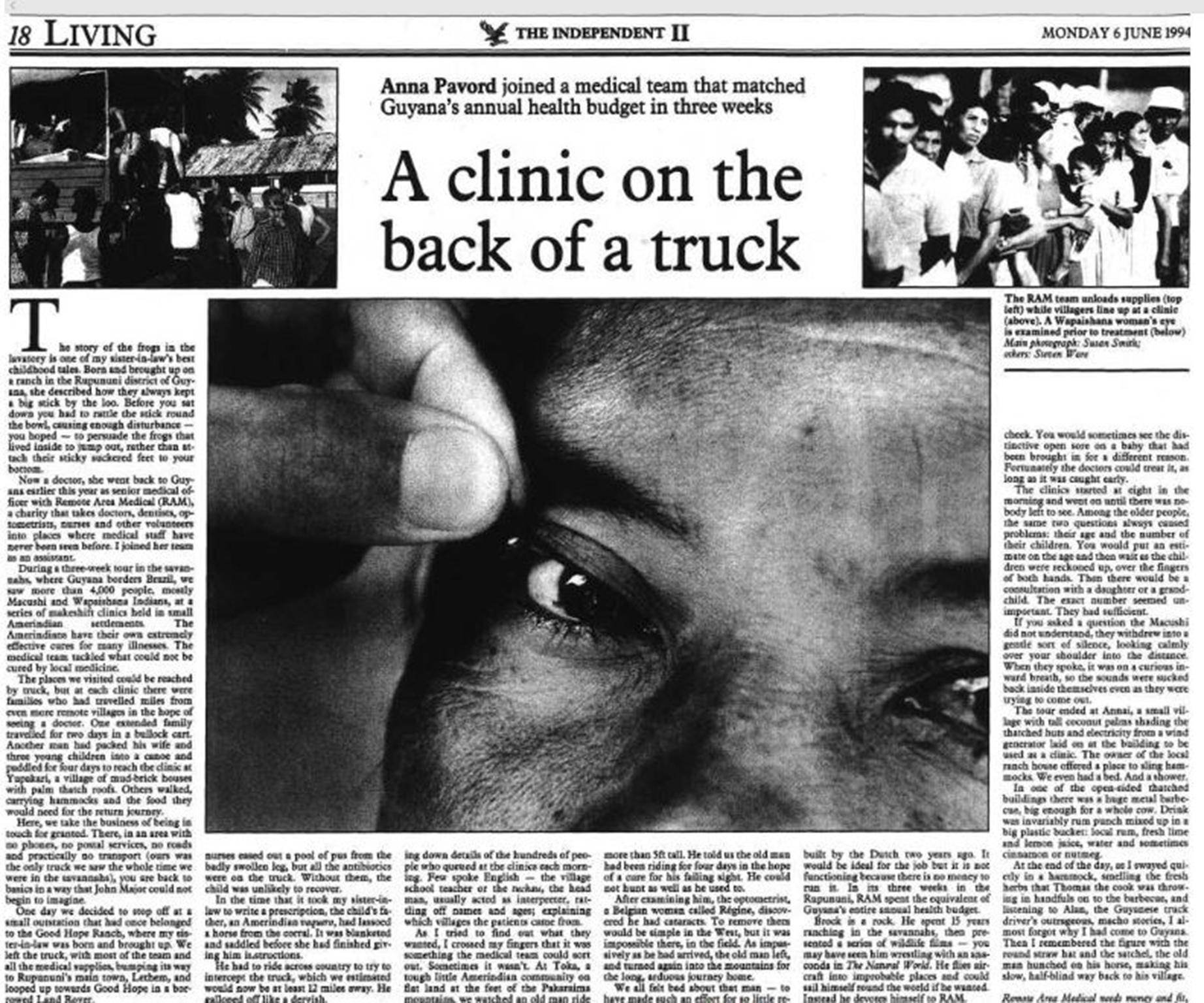

In 2014 The Independent published a feature entitled “Patients of a Saint” in which Simon Usborne spoke to the philanthropist Stan Brock. Brock died last week at a clinic he set up in Rockford, Tennessee, aged 82. Last year, Remote Area Medical – an organisation Brock founded to swoop in with airborne healthcare in the most “god-awful” places – attracted hundreds of people in need of medical assistance at a makeshift field clinic in Virginia. Brock said: “I expected to see stuff like this in South Sudan and Haiti but it’s right here in the United States of America.” He added: “I just wish I could get President Trump to come and see this.” The article is reproduced in full, below.

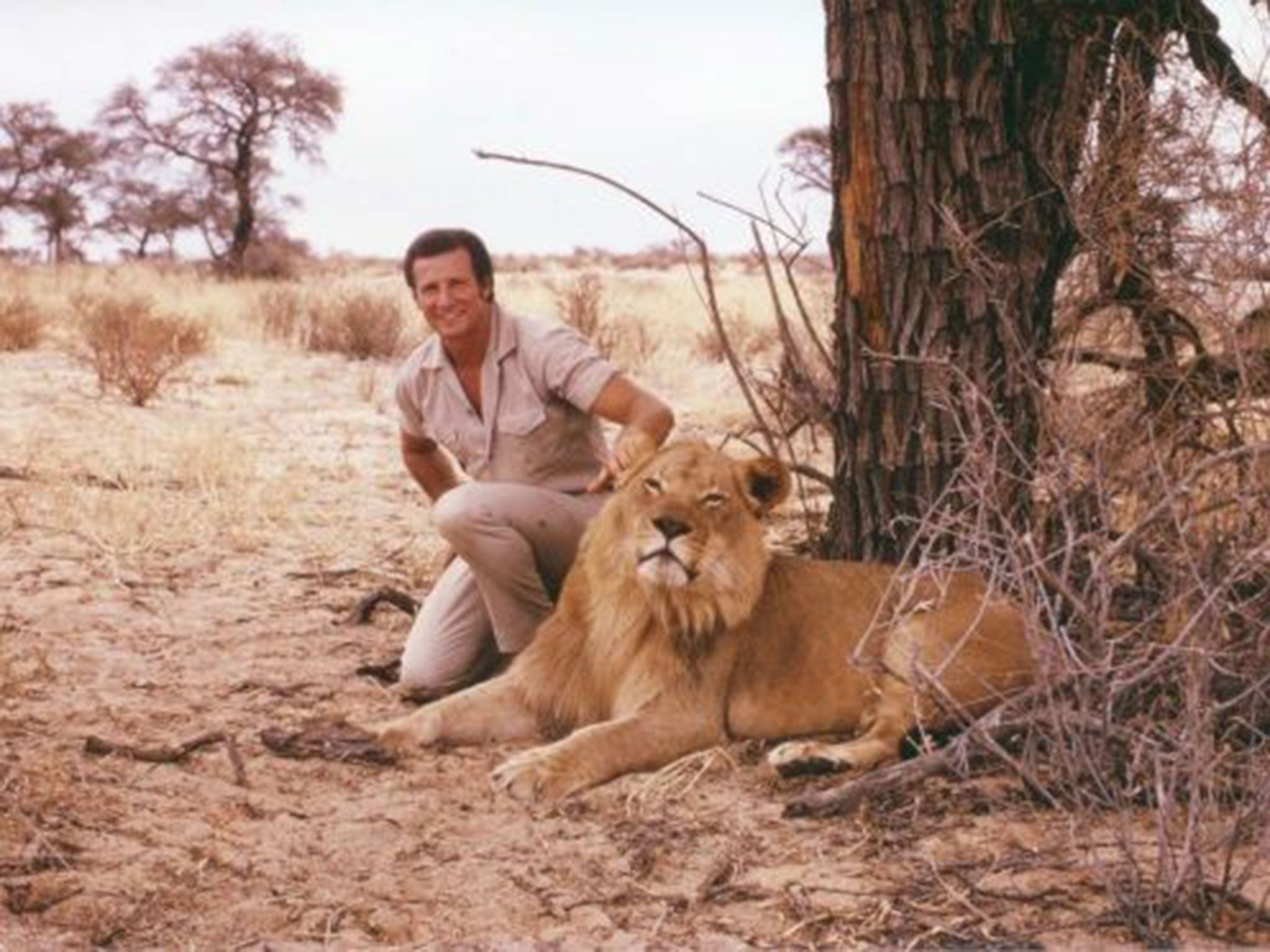

Stan Brock is nudging 80. His arms, hard as oak boughs, hint at the black belt he holds in taekwondo. His khakis and dust-stained shoes recall a previous life on horseback as a cowboy in the Upper Amazon.

Carefully combed hair nods to a brief career as a movie star in films including Escape from Angola (from the man who brought you Flipper). And the epaulettes and badges signify his role as the flying founder of a charity that has earned him a reputation as, variously, a saint and a “medical monk”.

Brock is staying in a hotel during his first visit for decades to Britain, where he grew up, only to run away to Guyana in South America as a teenager. Back in Tennessee, where he now lives, he is homeless and penniless, rolling out his cowboy’s mat each night inside the offices of Remote Area Medical (RAM), which he established in 1985. He eats only rice, porridge, bananas and water, and rarely sits down. Yet a singular devotion to his cause has fuelled a mission to prop up the broken healthcare system of the world’s richest nation.

Trailed by a film crew, which is documenting his extraordinary life, Brock has been invited to London by the Royal Society of Medicine at a time when healthcare in Britain is emerging as a defining issue before the next general election. Politicians, medical professionals and charities all over the world are fascinated by his work. What began as a mission to parachute doctors and medicine into remotest Guyana, has mushroomed to become the largest operation of its kind in America.

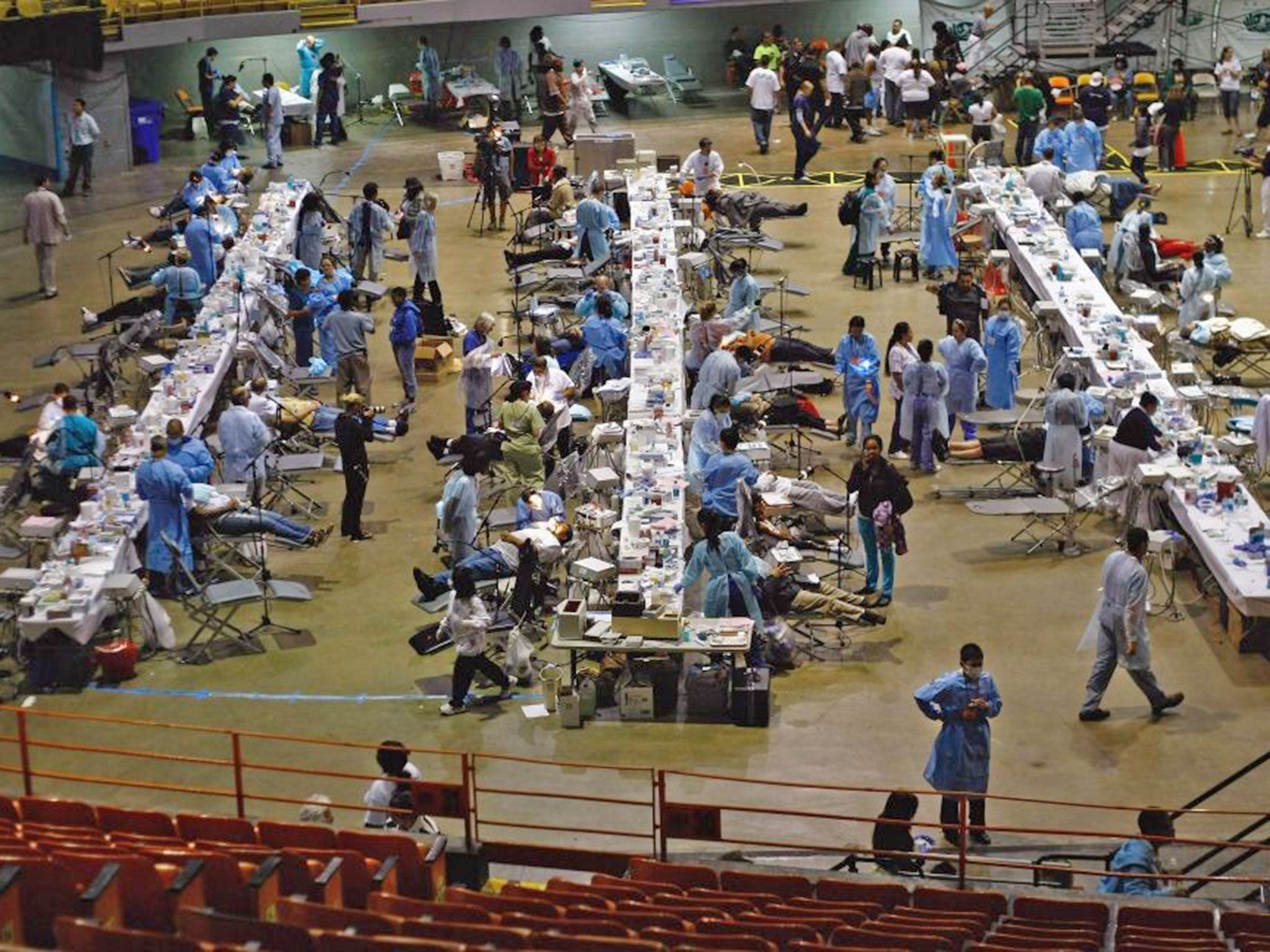

Brock has now organised more than 700 free clinics in convention centres and football stadiums. More than 80,000 volunteer doctors and nurses have provided free, basic, but sometimes life-saving healthcare worth more than £50m to more than half a million Americans, a fraction of a population who cannot afford to be treated or insured. Whole families queue, sometimes for days. This Thanksgiving, RAM, which has seven donated aircraft, will fly 100 dental chairs, 30 lanes of opticians and a small army of heart, women’s health and other specialists to a convention centre in New York City, just four miles north of Wall Street.

“You could be blindfolded and stick a pin on a map of America and you will find people in need,” Brock says. “We’ve never gone anywhere in the US where there wasn’t a big turnout. Only the geography is different. They’re all there to see the dentists, they’re all there to see the optician. And even if they don’t know it because they’re so preoccupied by the pain in their teeth, they all need to see the doctor, too.”

Brock, who is 78 and still has a British accent, explains the inspiration for his work with a story about an astronaut. “I had the privilege of having breakfast with Ed Mitchell, the sixth man to walk on the moon,” he says. “I told him that when I was a young cowboy, or vaquero, on the Brazil border of British Guyana, where all the cowboys were Indians, the Wapishana people gave me a horse that went bucking across the savannah and had a collision with the side of the corral.

“I was very badly injured but the nearest doctor was 26 days away on foot, through a narrow trail in the rainforest where you couldn’t take horses. Ed said: ‘Gosh, I was on the moon and I was only three days from a doctor’. Sure, I said, but for those people who lived in the Upper Amazon, and the 50 million people we’re now dealing with in the US, they might as well be on the moon for the opportunity they have to get the healthcare they need.”

Straight off his flight to London, Brock has come to see how free healthcare works in his country of birth. First, a look around a walk-in clinic in Vauxhall, where GPs are amazed to hear that poor Americans should need to rely on a charity that was originally conceived to treat people in the developing world. Then the short journey for dinner to the south London home of Clare Gerada, Britain’s most prominent GP and until recently the chair of the Council of the Royal College of General Practitioners.

Dr Gerada has put on a barbecue and invited doctor friends to meet Brock, whose work she discovered during a trip to Chicago. “Clare is the only British doctor who has had an opportunity to look at the state of affairs over there,” Brock says as they greet each other. Dr Gerada recalls her shock during a three-day RAM clinic at Malcolm X College, right inside the city’s world-beating medical district. She went in 2010 at the start of the controversial NHS reforms “to see what a privatised medical system would look like”, she says.

“I was humbled. These people were queueing all through the night in the rain. People like you and me, young people with families. When I was there, a young man died of a dental abscess. He died from a dental abscess.”

Earlier the same day, Ed Miliband had used Prime Minister’s Questions to switch the focus of Labour’s pre-election campaigning to the NHS during its radical reform under the Coalition. Days later, in a survey of senior NHS leaders by the Nuffield Trust think-tank, almost half thought healthcare would no longer be free at the point of use in England 10 years from now.

“What I learnt from Chicago is that we must never go down the route towards a marketised, competitive healthcare system,” Dr Gerada adds. “No matter what people say about the NHS, you will never fear cost. You will never fear that you will die from a dental abscess because you can’t afford to seek help.”

Brock, with his open-neck khaki shirt, cuts an incongruous figure in the genteel surroundings of Dr Gerada’s barbecue. As he tells his stories of men on the moon and taming horses in the Amazon, cheers drift over south London from the Oval cricket ground. He has become an expert in the complexities and failures of the US healthcare system, and often talks at congressional and senate hearings in Washington. But he has only distant memories of the NHS. What does it mean to him? “It means that at least everybody has a shot,” he says.

Recording the scene is Paul Michael Angell, a British documentary-maker who is halfway through shooting Medicine Man, a film about Brock. He, too, is fascinated as much by Brock’s medical work as he is his own story and unshakable devotion. “Stan’s in great shape but he has no house, wife or children,” Angell says. “His family is charity and his home is the office. I wanted to know what drives a man to do that and what he feels he has sacrificed.”

Brock’s story starts in Preston, Lancashire, where he was born into a modest home as the son of a civil servant. When his parents were dispatched to British Guyana, a colony until 1966, Brock was sent to boarding school in Dorset on a free scholarship. He was bullied by his more privileged classmates and, despite dreams of joining the navy, when he got the chance to visit his parents aged 17, he never came home. He fell in love with the wildlife, including jaguars, as well as the Wapishana tribe, whose land spans the forest and savannahs of the Brazil-Guyana border. He learnt their language, and became a cowboy, eventually running the vast Dadanawa Ranch. When an intrepid American wildlife film-maker visited in the late 1960s with a big camera and wooden tripod, he teamed up with Brock and made him a star.

Brock co-presented Wild Kingdom, which had 30 million viewers every Sunday night. Later, he got his own show: Stan Brock’s Expedition Danger. YouTube carries some of his work, including a documentary called M’Bogo Safari, in which he lassoes and then wrestles buffalo from horseback in Zimbabwe, and Escape from Angola, a 1976 film by Ivan Tors, of Flipper fame.

Brock, who wears the same outfit almost 40 years later, shirt still buttoned dangerously low, could have gone on to Hollywood and a comfortable life, but something was stirring beneath his swept-back hair. In 1983, he quit and sold everything he owned. Appalled by the high death rates among the Wapishana from treatable illnesses such as malaria, he returned to establish RAM, an airborne medical service to bring free healthcare to those in need. He still has operations in Guatemala, Haiti and beyond but early on realised that “there are Wapishanas everywhere”. Now operations in the US occupy most of his time and budget.

Dentistry and eye care are the most in demand but typically highlight other, often related, conditions and challenges. Bad teeth lead to a bad diet, and diabetes or hypertension. Bad eyes limit job prospects. “When the patient gets out of the dental chair after a full mouth extraction, or the kid who’s got glasses for the first time can see the leaves on the tree and they hug the dentist or the eye doctor, that’s a special moment,” Brock says.

All the doctors who hang on his words in south London have the same question: is Obamacare, the president’s fraught attempt to improve access to treatment, going to solve these problems? He pulls out a photo taken inside a senator’s office. Brock stands next to the full text of the Affordable Care Act. The pile of paper towers above him to a height of 10ft. “Nobody has been able to show us where it provides dentistry for adults or eye care and eyeglasses,” he says. “I don’t take sides politically. I’m not an American, I’m just the voice of the homeless and the under-served. But unless they fix these basic things, we’re going to be doing this long after my lifetime.”

The scale and spectacle of Brock’s operations in big US cities first attracted major media attention in 2007, when The New York Times magazine ran a series of black-and-white photos of a clinic in West Virginia. “They did 12 pages in black and white and it looked like Guatemala,” Brock recalls. “You had to read the captions to understand that this was the USA.”

Americans of a certain age remembered Brock from his television days, which has helped to raise awareness further. Current affairs shows including 60 Minutes followed and soon donations and voluntary support increased, but funding is always a challenge. RAM receives no government or big corporate money. “We just ordered $1.6m dollars of additional trucks and medical equipment, and we’re not in a position just yet to pay for it,” Brock says.

But what has been the cost of this work to Brock? He is a private man but there is talk of an early marriage that failed soon after he founded RAM, when his wife realised that his dedication was uncompromising. Does he regret not having had a family? Usually so quick with an anecdote, Brock pauses for some time. “I’m trying to think of a way to put this,” he says. “Would I like to be married? Yes. Would I like to have children…? Yes. But I’ve got thousands of them now.

“We did house calls on two of them just last week. A disabled 15-month-old living out in a shack in the woods in Tennessee, gonna require lifelong care, with a single mother who was brutally beaten by her husband. One can only do so much. It’s been a privilege to have provided care to a lot of people through RAM, but it’s a job that’s taken me 365 days a year, every year, for the past 29 years and a couple of months.”

And he’s not about to quit. “For the I-don’t-know-how-many years left I have on this earth, this isn’t the time to be sitting on the porch looking up at the Smoky Mountains,” he says. “I might as well do something.”

Stanley Edmunde Brock, born 21 April 1936, died 19 August 2018