Until recently, Mercury seemed to be the only planet in our Solar System without aurorae, those streams of light that appear on Earth in the polar skies when solar wind bombards the upper atmosphere with electrons.

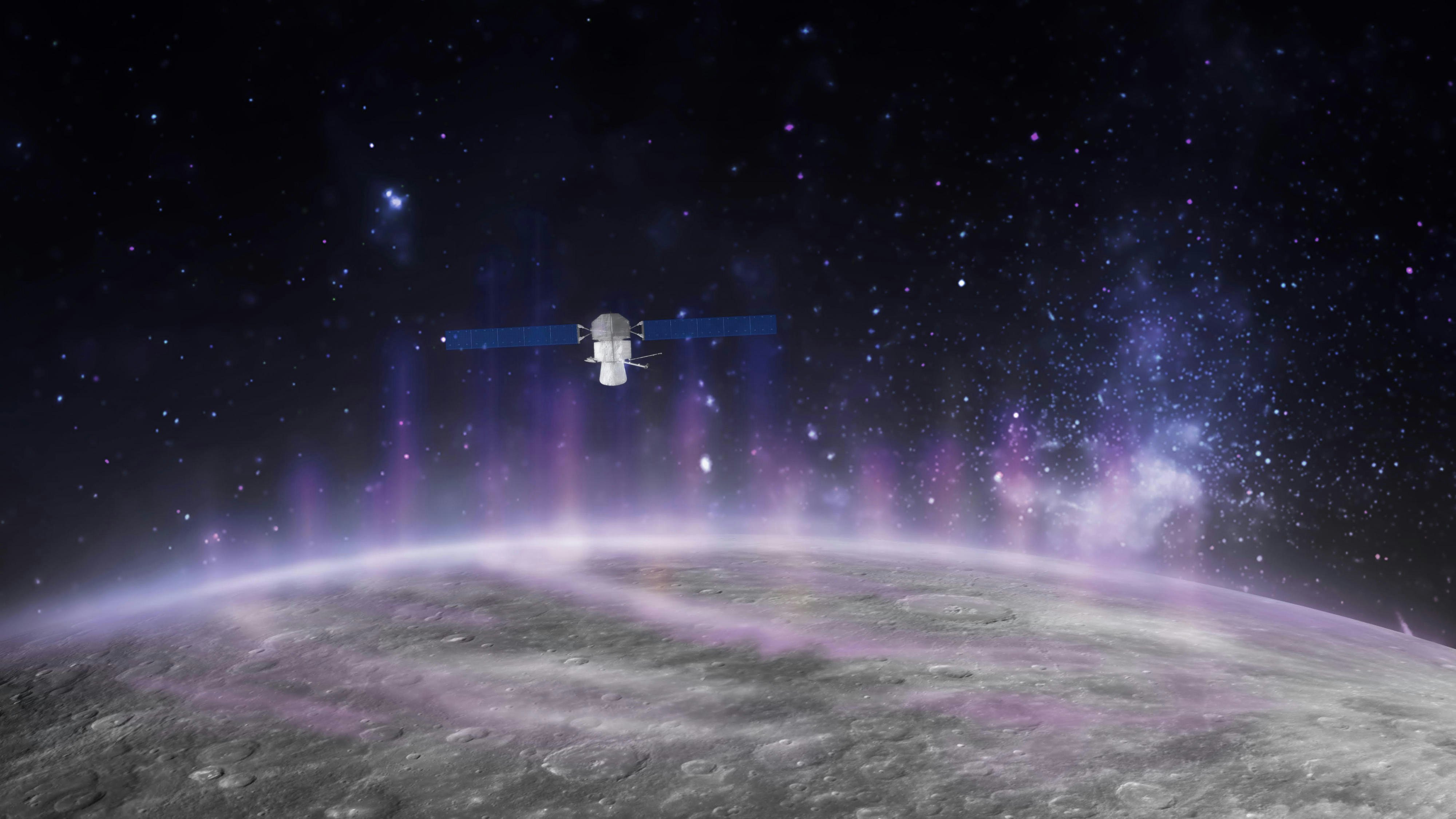

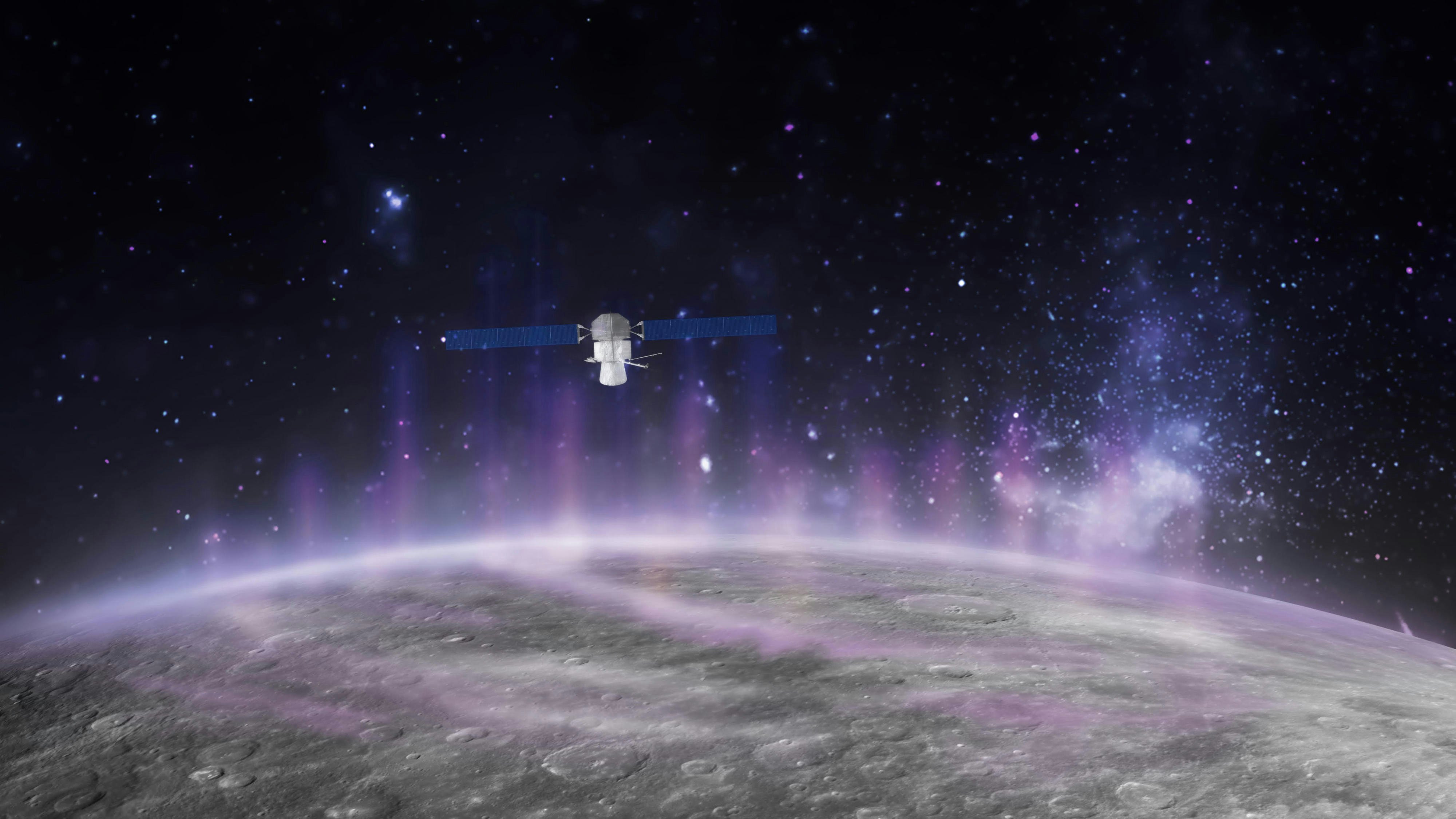

Mercury has no atmosphere for an aurora to appear in, after all, just a thin layer of atoms blasted free of its surface by meteoroids and solar wind. According to a recent study of data from the BepiColombo mission, Mercury has x-ray aurorae that make the ground itself glow with invisible light. As strange as the phenomenon is, though, JAXA planetary scientist Sae Aizawa and her colleagues say it’s caused by the same physics that create the familiar Northern Lights here on Earth.

The team of planetary scientist published their findings in the journal Nature Communications.

Spooky Glowing Ground

While BepiColombo (a joint mission of the European Space Agency and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency) swept past Mercury for the first in October 2021, its instruments were busy mapping Mercury’s magnetic field, as well as tracking the movements of electrons close to the planet.

Mercury gets bombarded by relentless solar wind, so the area of space around the planet is swarming with charged particles, mostly electrons. And when Aizawa and her colleagues examined the data from BepiColombo’s first flyby, they noticed that those electrons tend to get caught in Mercury’s magnetic field, which speeds the particles along magnetic field lines toward the planet’s poles. At the poles, electrons fall to the planet’s surface.

The same thing happens in Earth’s magnetic field, except that the charged particles have a whole atmosphere to fall through. On the way down, the electrons bump into atoms (our atmosphere is so full of atoms), and those collisions release energy, producing the Northern and Southern Lights. However, on airless Mercury, the electrons plummet straight to the ground. And that’s where it gets bizarre.

When electrons from solar wind, accelerated by Mercury’s magnetic field, rain down on the barren ground near the planet’s poles, minerals in the ground react by fluorescing, or emitting x-rays. The result is an invisible X-ray aurora blazing up from below, not shining down from above.

How flipping goth is that?

According to Aizawa and her colleagues, Mercury’s weird aurorae actually prove that the phenomenon works the same way on every planet in our Solar System (and almost certainly in other star systems, too).

Mars, for example, doesn’t have a proper, planet-spanning magnetic field, but patches of its crust contain rich veins of magnetic minerals, which sometimes they produce their own hyperlocal light shows. The electrons that bombard Jupiter’s stormy atmosphere mostly come from its volcanic disaster moon Io, rather than from solar wind, but the process that leads to aurorae is still the same (and Jupiter also has X-ray aurorae).

The basic mechanics that make x-rays dance across Mercury’s polar surface also light up the polar skies here on Earth — and on every other planet in the Solar System, plus at least one comet. Sometimes the results are just extremely weird.