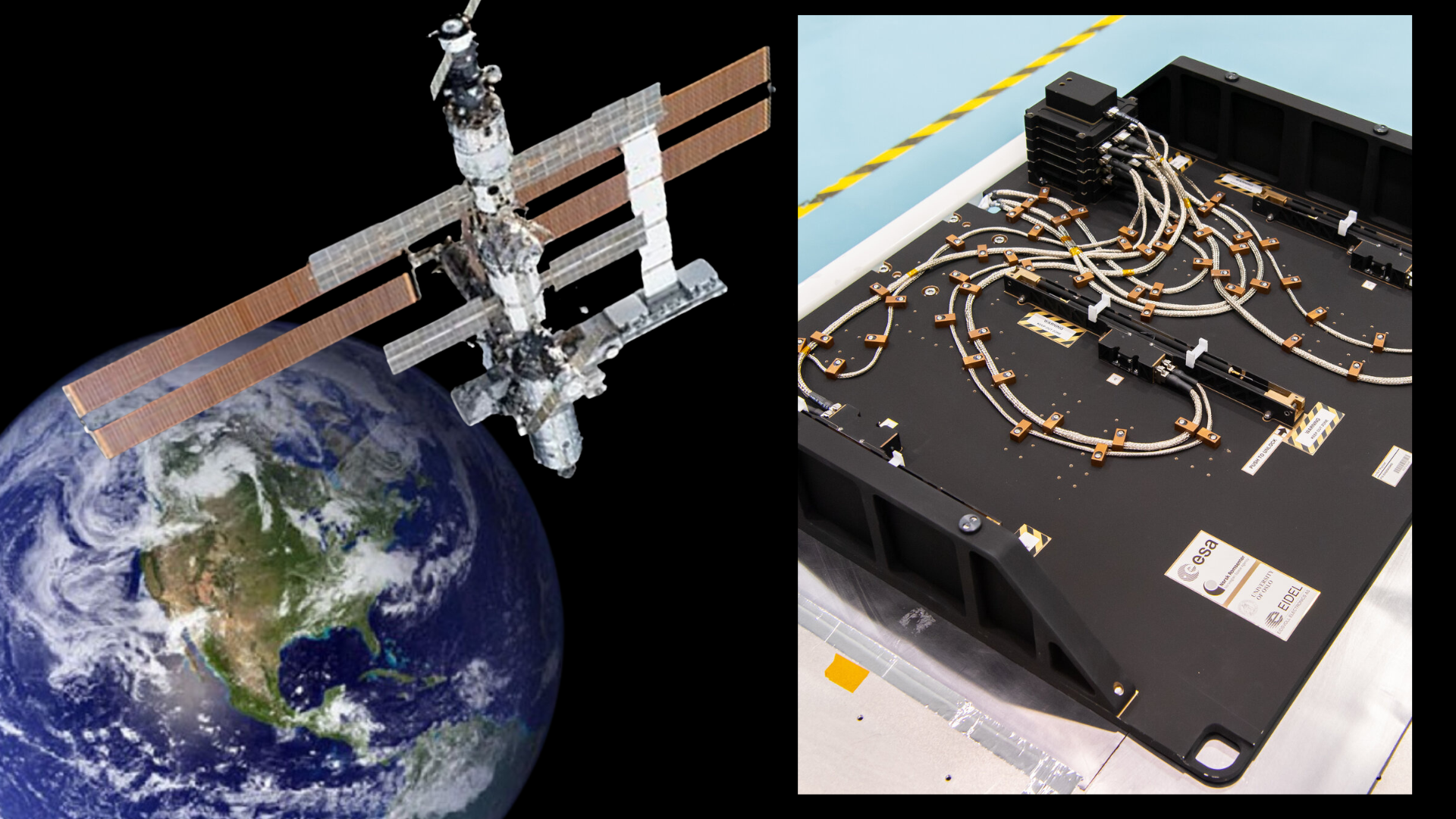

A new space weather sensor is heading to the International Space Station to help scientists understand how the sun's outbursts alter Earth's upper atmosphere.

The sensor's data will help space weather forecasters predict how sudden eruptions of radiation and plasma from the star at the center of our solar system disrupt satellite communication links and affect signals from navigational satellites such as Europe's Galileo.

Space weather is the result of charged particles from the sun interacting with the Earth’s magnetic field, or magnetosphere. While creating beautiful light shows over the poles called auroras, space weather can also have negative effects on satellites around the planet, even posing a risk to space missions.

The Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe will measure the density of charged particles around Earth down to a scale of just a few feet, with the six probes that comprise it gathering measurements up to an incredible 5,000 times per second, the European Space Agency (ESA), which oversees the project, said in a statement.

Related: Yes, solar storms are increasing, but don’t lose sleep over an ‘internet apocalypse.’

With a precision that is unprecedented, the instrument should allow scientists to build a more accurate picture of how radio signals from satellites are disrupted as they travel through Earth’s atmosphere to receivers on the surface of the planet. This should let researchers do things like determine where, when, and how these signals are disturbed, allowing them to better forecasts disruptions to the navigation and positioning services provided by satellites such as Europe's Galileo and the U.S. GPS.

The hardware for the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe is set to arrive at the International Space Station (ISS) aboard the Cygnus cargo freighter that launches from NASA's Wallops Flight Facility on Tuesday, August 1. The device will reach the orbital outpost ahead of the Crew-7 mission, which includes ESA astronaut Andreas Mogensen, who will oversee the space weather probe's installation.

Meet the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe experiment family

The ISS bound Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe will be placed on the Bartolomeo platform, located outside the European Columbus module.

Bartolomeo is capable of hosting experimental equipment about the size of a dishwasher. Experiments that sit on the platform are afforded with either a view of Earth or space, depending on how they are orientated. When placed at certain points of Bartolomeo, which was made by Airbus, experiments can also have a clear view of the direction that the ISS is traveling in as it orbits Earth at an altitude of 253 miles (408 kilometers) and a speed of around 17,000 miles per hour — around 11 times faster than the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter.

Versions of the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe experiment, created by the University of Oslo, Norway, and Eidsvoll Electronics from Norway, have journeyed to space before.

Between 2008 and 2019, working prototypes of the experiment were launched on sounding rockets to altitudes as great as 646 miles (1,040 km) over Earth with the aim of testing this technology.

In 2017, a simpler version of the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe was sent to a sun-synchronous orbit over the North and South Poles on the Norsat-1 satellite. The probe collected data for over 5 years granting scientists a great deal of insight into space weather in the upper region of our planet's atmosphere.

The version of the Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe experiment that will journey to the ISS on a cargo mission in the near future will gather data on space weather for around 3 years from a different orbit to its predecessors.

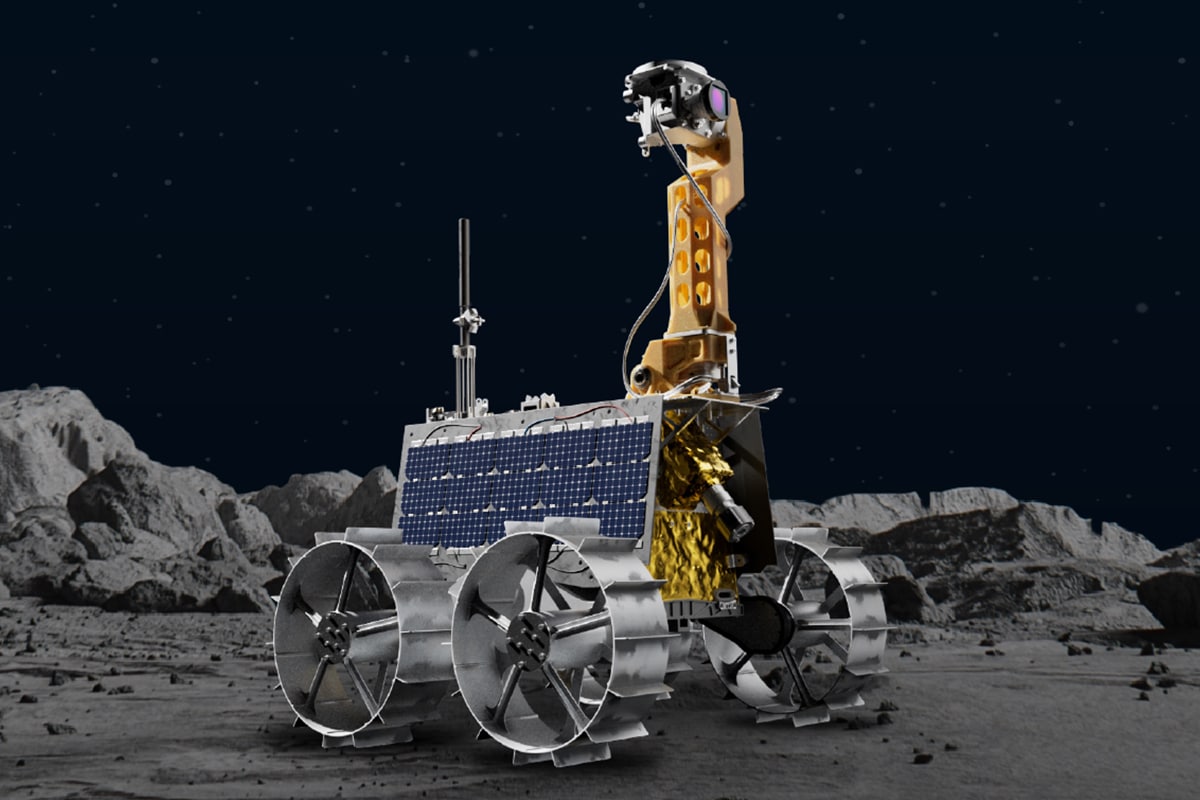

Another version of this experiment was scheduled to conduct science even further out than any of its kin, however. In December 2022 a Multi-Needle Langmuir Probe experiment began a journey to the moon aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. The experiment was part of Japan’s Hakuto-R lander and would have rolled out to the lunar surface on the Rashid rover.

Once on the moon's surface this version of the experiment would have measured how lunar regolith — loose, unconsolidated rock, mineral, and glass fragments in the soil — interacts with sunlight creating a gas of charged particles called plasma. The Hakuto-R Mission 1 failed when its operators lost contact with it as it made its descent to the moon in April 2023.