Joseph Stalin was no great lover of the arts, unlike other Communist leaders, but he recognised their power to stir his people’s souls in the pursuit of his political goals.

Stalin and the writer Maxim Gorky are both credited with defining, in 1934, the new style that would encourage this. Socialist Realism: art socialist in content and realist in style.

One of the burdens this new style had to bear in the capitalist West in later years was that it was labelled as formulaic, static and unemotional. Ironically, its purpose was the opposite: expression “saturated with ideas and feelings,” as writer Anatoly Lunacharsky put it.

Artists aimed “to show our heroes […] to catch a glance at our tomorrow,” in the words of Andrei Zhdanov, the politican who ran arts policy under Stalin. How they did it was surprisingly elastic: definition of style was never further specified.

The visual power of this work, describing an idealised, new world, first stirred me as a young woman travelling across Russia.

Vera Mukhina, for instance, made Worker and Kolkhoz Woman for Stalin in 1937 to show in the International Fair in Paris representing the USSR. This sculpture, now in Moscow, is huge, 24 metres high, made from what was then a new material: stainless steel.

The subtext of this sculpture was emancipation for women and experimentation with new technologies. It was hailed at the time as “the greatest work of sculpture of the 20th century”, the vigour and optimism of the two young people emphasized by their confident open gestures, dynamic, flying garments and steely, determined gazes.

No less than Picasso said, “How beautiful the Soviet giants are against the lilac Parisian sky.”

While this art movement was created in the Soviet Union, it did, in fact, significantly influence our own region: not just the art of Communist countries like China and Vietnam, but also Indonesia, the Philippines and even Australia.

I believe we should know this art, and celebrate it where merited. My aim is to ask people to think about their reactions to this work.

I’ve been questioned about art made in the context of political repression, and worse, in many of these places. I have long answers about equivalences of evil, but my best answer is to say art extends beyond the context of its creation, although understanding that context is important. In the end, the work stands for itself.

Here then, are ten examples of Soviet socialist realist art in our region worth our attention.

1. Welcome Monument, 1962, Indonesia

In Indonesia in the 1960s the Communist Party was the third largest in the world. Leading artists and Communists like Hendra Gunawan and S. Sudjojono, were sent to the USSR and East Germany respectively on cultural tours.

Indonesia’s first president Sukarno went to Moscow in 1956 and was so impressed he brought back both ideas and a Russian sculpture to his new post-Independence capital Jakarta.

Henk Nangtung and Edhi Sunarso’s Welcome Monument of 1962 carries the spirit and form of Vera Mukhina’s earlier work, challenging traditional Indonesian practice with its open body positions, and modern dress revealing muscle and flesh.

It tested the Indonesians technically and financially – Sukarno sold his personal car to help with the costs – but remains a central feature of Jakarta today.

2. For the man who said life wasn’t meant to be easy, make life impossible, circa 1976-78, Australia

Soviet influences impacted art practices throughout the Asia-Pacific region in many ways, particularly the idea that everyone, particularly “workers, farmers and soldiers”, would have access to the arts. Art schools in the USSR in the late 1920s decreed 60% of places be for the working classes, 30% for farmers and the rest for former upper classes.

The USSR was the first government to stipulate such ideas, edicts copied in Communist Asia – China, Vietnam, North Korea – but also influencing ideas of equity in the arts in Australia. The Community Arts Board of the Australia Council was founded in 1977 with the ideal of access for all, a criterion contentiously over-riding the idea of “quality”.

Celebration of “women’s work”, community art classes, access to artist working spaces in factories or country or regional areas, public art, and the employment of arts officers by local councils, all stem from this idea.

Political posters, often wryly funny, were often made by artist collectives like Earthworks, Megalo, Redback Graffix, Garage Graphix, Red Letter, Another Planet, Lucifoil and others. Collective practices put the individual’s interests second to the group.

This work by Chips Mackinolty, a member of the Earthworks collective, quotes former prime minister Malcolm Fraser’s famous line “life wasn’t meant to be easy” with the rejoinder typical of the anti-status quo position, that, for Fraser, we should “make life impossible”.

The visually arresting simplification of Fraser’s haughty face constrasting with the humour of the verbal rejoinder gives this work its appeal.

3. Standing Guard for our Great Motherland, 1974, China

Socialist Realism has been expressed in many ways. An important part was grand history painting. Russian works like Aleksandr Gerasimov’s portrait of Stalin and General Voroshilov on the walls of the Kremlin shows an idealised leadership, standing solidly together, literally looking out over Moscow to, what? Destiny?

In China, works like Shen Jaiwei’s Standing Guard for our Great Motherland, painted in 1974, were similarly recognised for their capacity to tell a tale of strength and determination.

Again we literally look up to two soldiers transformed into generic heroes looking out across the border river to (at that time) the hostile Soviet Union. This work was highly praised by Madame Mao.

I had travelled down that river just a few years before Shen Jiawei made his painting, watching gunfire between the two countries. I then flew over Vietnam during that war, landing at the old Bangkok airport with the tarmac covered in American military planes.

A few weeks later I was on the train going down the Malay peninsular as Communist insurgents carrying AK-47s jumped on and off my carriage. I felt this history had become personal.

4. Lithograph, 1968, China

I went back to Moscow in 1979 officially for the Australian Gallery Directors’ Council, negotiating the passage of an exhibition Old Master drawings from Australian museum collections. I felt the full force of the Soviet bureaucracy – a dispiriting reality-check to my earlier romantic vision.

I bought posters in Moscow at that time made in the great Soviet graphic traditions encouraged since the Revolution, created by artists like Aleksandr Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, also socialist in content, realist in style.

These images had spread widely, especially in China, with huge print runs in both the USSR and the People’s Republic. They adapted traditional imagery – the folk print and papercut – often combining word and image, with pared down colours and simplified lines, but adding the exaggerated heroic figures with clenched fists and glistening eyes that have since become icons of Chinese art.

Though this Chinese lithograph, made collectively by the city of Tianjin’s publishing house, refers to the simplified outlines of traditional folk imagery, it would not have achieved its power without its forebears created in the USSR.

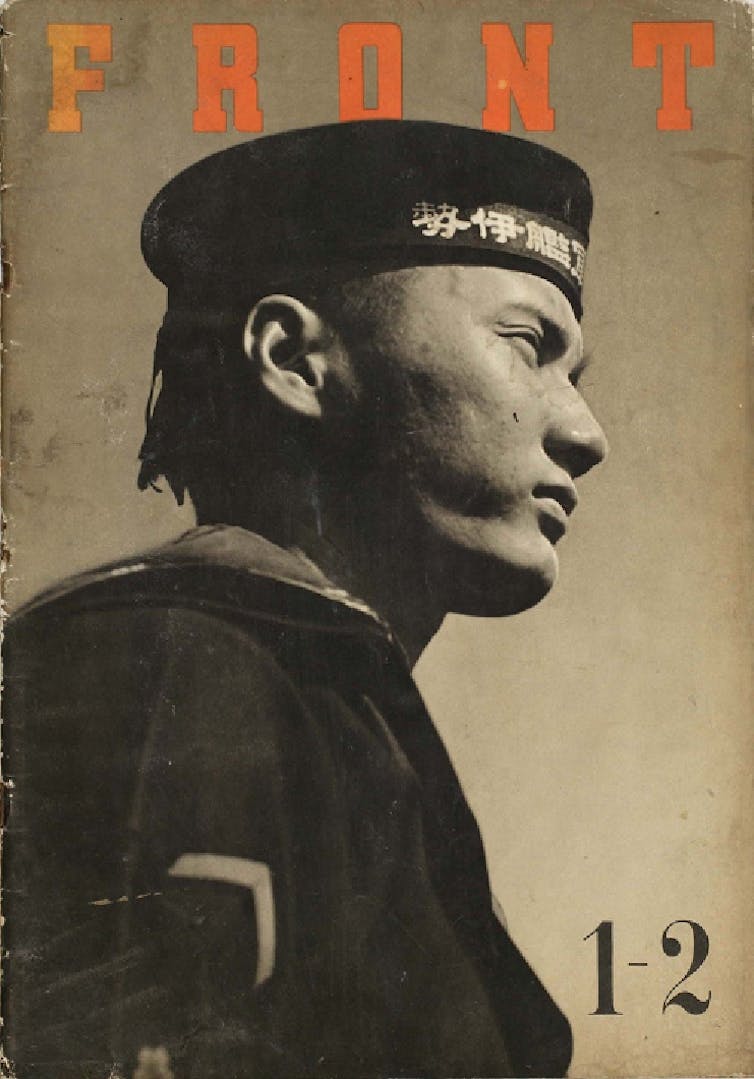

5. FRONT magazine cover, 1942, Japan

In Japan before the second world war, the right-wing militarist government recognised the effectiveness of Soviet graphic imagery, using it to transmit a very different political agenda.

FRONT magazine, produced to support the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere during the war, follows the Soviet models in its use of angled views, text and image, duo-tones and images that bleed over the edge of the page, but with a higher quality of production. This magazine in turn influenced publications made in Java, like Djawa Baroe, to support Japanese rule there.

6. Meeting of Northern and Southern Fighters, 1954, Vietnam

Socialist Realism is a flexible style. The Vietnam National Fine Arts Museum in Hanoi privileges Socialist Realism from the 1950s to the Doi Moi reform period in the 1980s, but it is a personal, human-scale imagery with small works often of domestic or pastoral scenes. They are frequently painted in watercolour, using the techniques learnt from their School of Paris colonial-era teachers.

The Communist Vietnamese entrusted soldier-artists to communicate the experiences of their fellow combatants during the Vietnam (American) War against the capitalist West. One of these remembered:

The morale was high. We soldier-artists felt thrilled with our task, witnessing the battle. On the other hand, our troops felt honoured at having soldier-artists in the company, our drawings glorified their sacrifice and even their death.

The warmth of greeting of the two soldiers from different parts of Vietnam fighting for their independence in 1954 is the ruling emotion of this sensitive watercolour work.

Trinh Phong is an artist fully conversant with Western techniques – the wash medium, compositional construction, use of light and shade, and anatomical accuracy.

In his study of two comrades meeting he uses them to subtly affirm the human bond between the two men and their belief in their cause.

7. Olympia, Identity with Mother and Child, 1987, Indonesia

Young artists in Southeast Asia usually used the socialist message and realist means to critique rather than glorify the status quo.

Indonesian Semsar Siahaan painted his Olympia during Suharto’s regime. It references the famous Manet painting of the Parisian prostitute refigured as the blond tourist in Bali fawned over by officials while the people starve.

8. The Second Coming, 1994, Philippines

The Filipino collective Sanggawa made The Second Coming in 1994, some years after president Ferdinand Marcos was deposed. But they were still clear in their intent to cast a critical light on the failings of those in power.

The painting interprets the visit of Pope John Paul to Manila and the role of local Cardinal Jaime Sin, here depicted as the accompanying singer to the left of the Pope.

It was a time, the artists wrote, when “religion and entertainment then became the prevalent theme”, when the religious organisation El Shaddai said “liking money is not at all a sin, and through it all sin, sin and more Sin”. This huge canvas asks people “to confront and laugh at their demigods, that they may discover their real voice from within”.

This, like Siahaan’s, is a very large, grand, history painting, full of political message, humour and intent.

9. Chinese Communist Party anniversary performance, 2021, China

The above works were made in the 1980s and 1990s, but what of today? Is this style of art still relevant? The Chinese say it is alive and well – witness the the imagery made for the 100th anniversary celebration of the Chinese Communist Party in 2021: socialist in content, with the bravura and theatrical dramatisation of the earlier grand set pieces.

The image below is a still photograph of a theatrical performance on the 2021 anniversary, visualised in classic Socialist Realist terms.

10. Buruh bersatu (The workers unite), 2003, Indonesia

The same goes for Indonesia. The last Documenta exhibition in Germany, which explored the idea of collectivism, was curated by the Indonesian group Ruangrupa.

It included work by Taring Padi, the collective based in Yokyakarta with a large international reputation. Their members contribute to projects often in the public space, but usually with political purpose aimed at creating a brave new world focused on “the people”.

A series of large (2.4 metre tall) and impressive woodcuts now in the Queensland Art Gallery is typical of the scale, energy and commitment of their work.

Vignettes of people building a complex web of life in the cities, factories and countryside are bound together by the central banner stating “Buruh besatu”, or “The Workers Unite”. Protesters, meanwhile, carry the sign “build solidarity between workers and oppressed people”. You feel Lenin would have been pleased.

This contemporary resonance extends to Australia too, with now Sydney-based Shen Jiawei’s Tower of Babel the subject of a new film Welcome to Babel, winner of the documentary award at the 2024 Sydney Film Festival.

In a seeming bookend to his early Standing Guard work made 50 years before, Shen has included many forgotten people who tragically lost their lives to the revolution in this set of four, huge, painted assemblages.

But, as the filmmakers say, the new artwork also includes over

400 famous and infamous characters including politicians, soldiers, scientists, artists, writers and filmmakers who believed in the utopian vision of the Communist movement.

Alison Carroll is the author of Soviet Socialist Realism and Art in the Asia-Pacific, Routledge Research in Art and Politics, 2025

Alison Carroll does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.