How does it come about that a man who dedicated the greater part of his life to a vision of a just South Africa, and sacrificed his family and personal relationships to do so, disappears from the annals of the country’s history?

How does a writer with consummate command of two of South Africa’s national languages – English and Afrikaans – and whose work in poetry and prose reflects deep insights into world politics, literature and culture come to be virtually totally forgotten?

This is what happened to Frank Anthony, a South African author and activist who lived a life committed to ending racial, economic and gender injustice in apartheid South Africa. Anthony was born in 1940 and died in 1993.

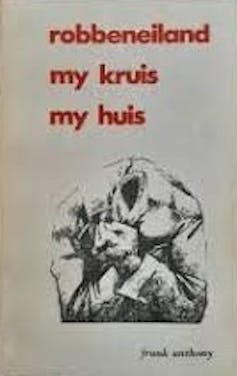

He is the author of an Afrikaans poetry collection Robbeneiland: My Kruis, My Huis (Robben Island: My Cross, My Home) and the novel The Journey: The Revolutionary Anguish of Comrade B. Both works draw on his six-year incarceration on Robben Island, and the impact of being restricted within the Kraaifontein district of Cape Town for five years after his release.

I have studied his works, and his life, over the past three years, and have distilled my findings in a recently published article on his novel The Journey.

The novel is set in the 1980s. Yet it seems to speak to the betrayal and crisis of leadership experienced in South Africa at the present time. I am also interested in the ways the novel seems to exclude personal relationships, especially romantic love, in its political vision.

Investigating Anthony’s life and work, I discovered that his political and literary contributions had not been recognised. Almost no information is available about him online. Both his publications are out of print, so not easily available to the general reading public, and his work has completely fallen out of view in South African literary studies.

In my view this is because of his implicit criticism of the leadership of the political organisation to which he belonged, the African People’s Democratic Union of Southern Africa, which has expunged his presence and his political contribution from their website. Another factor was the racialised way in which his poetry and fiction were viewed. Reviews of his poetry collection at the time of its publication, for example, focus on the racial identity of the poet rather than on the literary sophistication of his collection.

For me, Anthony’s experience amounts to censorship and “banning”. This was something many South African writers experienced at the hands of a number of apartheid laws and censorship boards.

It also echoes the experience of dissident writers in Africa such as Nuruddin Farah, as well as international writers like Václav Havel who challenged authoritarian regimes through their life work and writing.

The times

Anthony was born in Stellenbosch in 1940. Stellenbosch is a town in the Cape winelands, steeped in colonial history. It is still home to the descendants of enslaved people brought by the Dutch to the Cape from the mid-17th century.

Apartheid segregation and discrimination were layered onto this history by the National Party, which came into power in 1948. This was the society into which Anthony was born, and the context that influenced his political allegiances.

He joined the Non-European Unity Movement, and later its affiliate, the African People’s Democratic Union of Southern Africa.

In 1972, Anthony was arrested and convicted on four counts under the Terrorism Act. The act gave the apartheid government the legal power to clamp down on resistance movements.

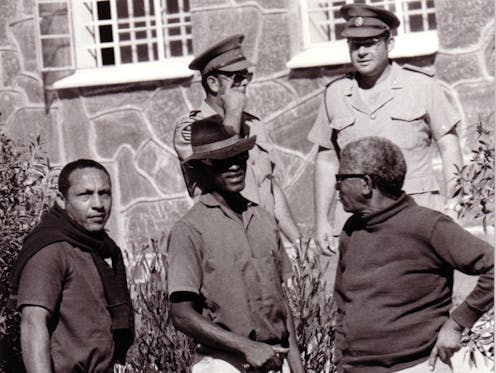

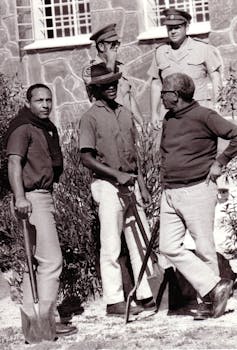

Anthony was imprisoned for six years on Robben Island. Leaders like Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu of the African National Congress were serving their sentences there at the time.

On his release in 1978 Anthony was put under a banning order. This meant that he was physically restricted to the Kraaifontein area, a semi-rural district of Cape Town. He worked at a supermarket in the area even though he was a qualified economics lecturer.

After his banning order was lifted, Anthony again become involved in clandestine anti-apartheid operations.

Contributions to literature

Anthony was one of a number of significant writers of his time who acknowledged that literature and culture reflected – and were affected by – politics. Other celebrated South African writers, including Mongane Wally Serote, Don Mattera and Nadine Gordimer, also believed that literature had the power to transform hearts, minds and the world.

Anthony’s Afrikaans poetry collection, Robbeneiland: My Kruis, My Huis, was published in 1983. It was titled after the extended poem where he reflects on his prison experience. This poem was also published in the well-known resistance literary magazine, Staffrider.

The collection was the first example of Afrikaans prison literature, and an exemplar of how Afrikaans could be an African language of resistance rather than “the oppressor’s tongue” as it had been seen, following the 1976 Soweto youth uprising, when Afrikaans was imposed in black schools.

But the poetry collection has not been studied for its literary qualities and its creative exposition of debates and philosophies. Rather it has simply become a footnote in Afrikaans literary scholarship.

Anthony’s 1991 novel, written in English, has been almost completely elided from history, despite receiving good reviews in the South African press when it was published.

The highly satirical novel allegorically tells the story of the journey of Comrade B through South Africa to a neighbouring country where his political leaders are exiled. The organisation is never named in the novel.

Read more: Epitaph for a baobab: remembering South African poet and activist Don Mattera

The novel uses well-known literary allusions to foreground the idea of betrayal, especially by leaders who seem to have lost touch with realities on the ground.

The organisation Anthony was still close to read the novel narrowly and defensively. The leadership saw it as an autobiography rather than as a novel, presenting a non-fictional critique of organisational and leadership failings.

In its response to the novel in newsletters and other correspondence, references were made to the “mental instability” of its author.

Importance

In my view the novel is important for a number of reasons.

Firstly, it highlights the idea of betrayal of ethical and political principles. Current disillusionment with political parties is not new.

Secondly, the narrative seems, by omission, to be highlighting how personal lives and relationships, especially romantic love, might be a politically radical concept. The novel, following dominant Marxist theory, regards love as a bourgeois preoccupation. Contemporary leftist and radical black debates, by contrast, have re-evaluated the importance of love in political struggle.

Today the novel is available only at the Library of Parliament, the National Library of South Africa, and a handful of university libraries. Its disappearance impoverishes our understanding of activists and resistance movements, and their missteps and misapprehensions, in the South African context, as well as worldwide.

F. Fiona Moolla does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.