Lockdown was, among other things, a sudden collective experiment in volume control. Sound waves from the regular rush-hour thrum of cities usually penetrate more than a kilometre below the Earth’s surface. When Covid-19 forced humans inside, seismologists noticed the muzak of their subterranean instruments was quieted. The ancient rock of our planet came closer to the silence that it had known for nearly all of the first 4bn years of its existence. And the relative stillness was felt on the surface, too. People noticed voices from beyond the human world a little more readily, and those voices felt less need to shout to be heard. Scientists in San Francisco discovered that the city’s sparrows reverted to softer and lower pitched songs of a kind not heard since the invention of the freeway.

Biology professor David George Haskell’s often wonderful book is all about listening to those kinds of lost frequencies. It is a sort of rigorous scientific update on that 1960s imperative to “tune in and turn on”: a reminder that the narrow aural spectrum on which most of us operate, and the ways in which human life is led, blocks out the planet’s great, orchestral richness. Haskell’s previous acclaimed book, The Forest Unseen, was a thrillingly curious investigation of the life of one square metre of ancient Tennessee woodland. This new volume gives you the experience of closing your eyes in such a space and having your senses flooded with the background cacophony.

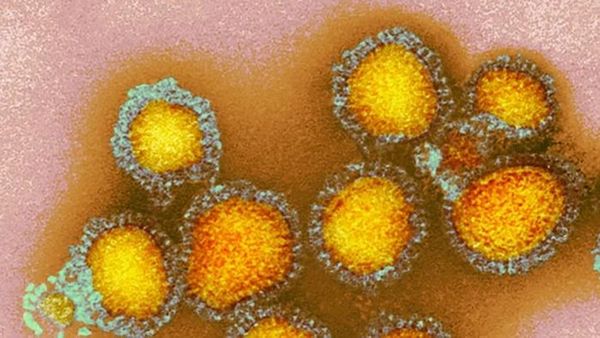

It took our sun a good while, Haskell argues, to work out the means of filling the planet with sound. Eventually it discovered the cymbal crash of life. A microphone in a muted laboratory can pick up the sounds of colonies of bacteria. When these are amplified and played back to the bacterial cultures they grow at an accelerated rate, detecting the noise through cell walls. No one knows how or why. Bacteria had this ultimate chill-out playlist to itself for nearly 2bn years. The first sea creatures were voiceless. The evolutionary quirk that set life on the road to hearing was a “tiny wiggly hair”, a cilium on a cell membrane that allowed organisms to “hear” eddies and changes in water flow that might help them to locate food. Haskell traces, beautifully and brilliantly, the stages from that development to the wonders of human and animal hearing – all the infinite serial interactions between communication and reception. “When we marvel at springtime birdsong, or the vigour of chorusing insects and frogs on a summer evening,” he writes, “we are immersed in the wondrous legacy of the ciliary hair.”

Crickets and their ancient relatives were among the prime movers in this evolutionary soundscape. In immersing himself in the mechanics and music of insect song, Haskell transports his reader to imagine the first instruments and notation: he examines the fossil tracery of prototype grasshopper wings, preserved in Permian rock, which clearly reveal the shift from a flat surface to one with an unusual ridge, the gene genie mutation that allowed the insect to create and amplify its sawing sound. Such discoveries lead Haskell to all sorts of places: the development of echolocation, the “hearing feet” of certain species, the insatiable human need to recreate and delight in Caliban’s isle “full of noises”, and the ways in which technology – from antler-horn pipes to reed instruments to digital soundtracks – has often advanced in creating through rhythm and music.

The earliest ears of all species were on high alert for novelty – just like teenagers hungry for the newest beats. Some corners of the animal world are richer with this kind of innovation than others. Humpback whales, Haskell writes, concentrate their hit factory in “an innovation zone” off the coast of Australia, where new calls are developed and tested. Once established, the latest humpback songs will have spread throughout the oceans within a few months. Tragically, evidence suggests, this natural wonder has met with brutal interference in recent years: the calls of whales and dolphins can get lost in the “sonic fog” produced by container ships’ engines. Mating and distress calls go unheard. And oil prospectors’ sonic surveys, producing underwater decibel explosions every minute, are thought to have forced whales – enormously sensitive hearing creatures – out of the ocean to escape the torture.

Human noise pollution is everywhere on land and Haskell’s investigation into natural sound often takes on the tone of a valedictory lament. He goes in search of wild places – forests at dawn, riverbanks at evening – where the diversity of bird and insect noise is at its overwhelming richest, and contrasts them with the eerie silent springs of pesticide-scoured agrarian landscapes. The ambition to tell the history of our planet through description of sound is given a profound urgency by these chapters. Meanwhile, the sense of what is being lost is revealed in how even the thesaurus of Haskell’s descriptive language struggles to keep up with the nuance and variety of the musical world. You often sense him, as he attempts to convey in words what he is hearing, in the position of Keats: no match for the nightingale.

• Sounds Wild and Broken by David George Haskell is published by Faber (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply