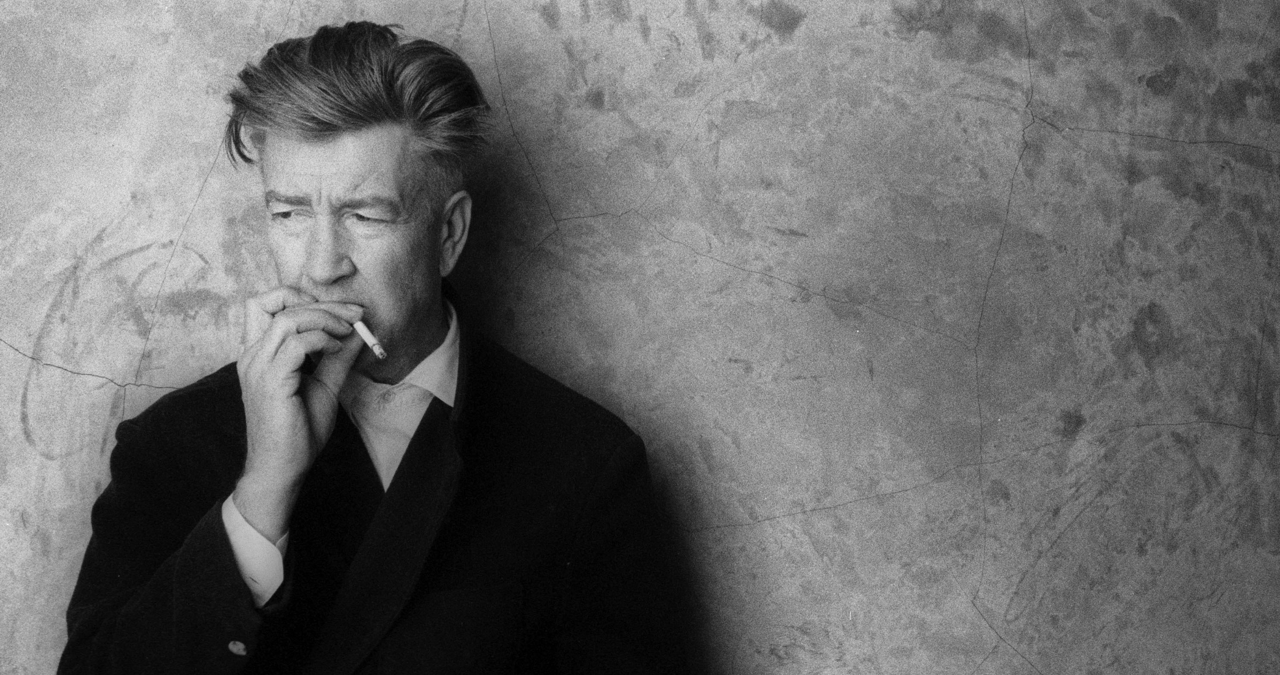

On January 16th 2025, it was announced that filmmaker, writer, artist and musician David Lynch had passed away at the age of 78. Though Lynch will primarily be remembered for his extraordinary filmography, and for helming the iconic television phenomenon, Twin Peaks, the full extent of his influence on creatives across various forms of media is incalculable. It’s no exaggeration to say that a footprint of equal size to the one he left in cinema is also detectable in the music world.

“Cinema is sound and picture moving together through time,” was an oft-repeated mantra of his, and his amalgamation of the two art forms was core to why many of his most cherished films have left such a lasting impression in the hearts and minds of generations of aspiring music and film-makers.

From the very beginning of his career, Lynch had a fixation on how the juxtaposition of sound and picture could resonate in a much more potent way than was typical in contemporary film scores.

The eerie, discomforting sounds that Lynch crafted with Alan Splet to permeate the aural world of his debut film, Eraserhead (1977), were an early indication of the central role that sound would play in his career.

That same attitude of using sound to evoke emotions, anxieties, tension and suspense could be traced all the way through his ensuing body of work. Across ten feature films and four television series, all the way up to his final major project, 2017’s Twin Peaks: The Return. In particular, the beloved eighth part’s violent aural shifts and discordant chaos when depicting the Trinity test.

“People always talk about the look of a film, they don’t talk so much about the sound of a film,” David said in the 2019 documentary Making Waves. "But it’s equally important. Sometimes more important.”

Lynch’s perception of sound and vision being equally important also applied to how he deployed music, from the queasy use of saccharine vintage pop amid the escalating mania of 1986’s Blue Velvet, the intense, industrial metal-tinged soundtrack to 1997’s Lost Highway and Lynch’s first major foray into songwriting, back on 1977’s Eraserhead, with the unsettling ‘In Heaven’.

It’s understandable then, why Lynch was so hands-on with both the sound design and the music-making process behind many of his projects, though it was Angelo Badalamenti (who sadly passed in December 2022) with whom he’d have his most significant musical relationship.

Originally meeting during the making of Blue Velvet, the pair struck up a strong bond. "Angelo, he can do anything, he can write any kind of music," Lynch told the BBC in 2023. “The secret to Angelo is that if you know what you want, you've got to bring it out of him. It's there in him but you've got to bring it out.”

And bring it out of him he did. Across five films and three television projects, Badalementi realised Lynch’s often opaque visions. The most important work - and the work which has arguably left the biggest impression on the ears, hearts and attitudes of music-makers - is the score to Twin Peaks.

The cultural phenomenon - which originally ran from 1990 to 1991, spawned a film in 1992, and returned for a sublime third and final series in 2017 - also sported one of the most gorgeous opening themes ever recorded.

An instrumental arrangement of Julee Cruise’s Falling (which Lynch, Badalamenti and Cruise has previously written and produced together) was awash with gorgeous waves of synth and string sounds, whilst a gradually ascending and descending melodic motif gently pulsed back and forth.

Set to a slowly fading montage of the town’s logging machinery, a flowing waterfall and an orange thrush, the show’s opening signalled an exit from reality into a more serene, dream-like plane.

Twin Peaks’ gradual descent from its small-town murder mystery beginnings into the all-out nightmare of its original finale remains one of the all-time great television thrill-rides.

Twin Peaks’ soundtrack could swing almost as dramatically and unpredictably as its narrative. At any point, scenes could be accompanied by bossa nova , sultry jazz, unnerving dark ambient synth drones and melodramatic piano-based character themes (often in the same cue!) or the haunting dream-pop of Julee Cruise - It was a score that was an inconstant yet central character.

Twin Peaks original series left an indelible mark on those watching at the time, and those who’d absorb it later on VHS and DVD. Artists as diverse as Moby, Sky Ferreira, Beach House, DJ Shadow, Bastille, Lana Del Rey and Au Revoir Simone (who’d later appear in the third series) have cited it as a direct influence or referenced it in their works.

It's perhaps for this inextricable link between Twin Peaks, David Lynch and music that for each of the 18 episodes of the 2017 series, a regular musical performance would take place, typically to close out an episode.

Artists including Chromatics, Nine Inch Nails, Eddie Vedder, Au Revoir Simone, Sharon Von Etten and Julee Cruise took to the stage at the town’s Bang Bang Bar and perform a full song. For most television shows, suspending the narrative for a full-length musical performance would feel quite jarring. Not so with Twin Peaks.

Musicians who’ve worked with Lynch recall a free-flowing, idea-led process that shunned the technical and was governed by a desire to synergise sonic experimentation with often abstract visuals.

Trent Reznor recalled how, when working on 1997’s Lost Highway, Lynch would excitedly articulate what he wanted from a musical perspective; “He'd describe a scene and say, 'Here's what I want. Now, there's a police car chasing Fred down the highway, and I want you to picture this: There's a box, OK? And in this box there's snakes coming out; snakes whizzing past your face. So, what I want is the sound of that - the snakes whizzing out of the box - but it's got to be like impending doom." And he hadn't brought any footage with him. He says, "OK, OK, go ahead. Give me that sound."

Beyond its incorporation into his film and television projects, music remained a creative fixation of Lynch’s. “I’m not a musician, but I play music,” Lynch told Sight and Sound in 2009. “I started doing it just to make sounds, experimental sounds, and it’s led to something.”

At his Asymmetrical Studio, which he built in 1997, Lynch would record his own explorations of sound, lyrics and music.

Records such as the industrial BLUEBOB (a collaboration with John Neff), the gnarled fusion of sound design and guitar found on 2011’s Crazy Clown Time and the fragmented blues-meets-electronic tracks of his final release, The Big Dream in 2013 reveal a prolific musical journeyman. "Sometimes the lyrics come first but mostly the music is talking to you about how it wants to be, and then the lyrics are born out of that,” Lynch told Billboard. An insight into a man whose overriding creative philosophy was dictated by the notion that ideas are constantly swimming in the ether.

Lynch stated in his creative strategy book ‘Catching the Big Fish’ that, “ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper. Down deep, the fish are more powerful and more pure.They’re huge and abstract. And they’re very beautiful.”

In the wake of his passing many musicians took to social media to share their sadness.

Smashing Pumpkins Billy Corgan, who worked with Lynch on Lost Highway, said “Truly saddened to hear of the passing of David Lynch. Working with him was like a dream out of one of his movies, and I treasure the times I got to speak with him and hear first-hand his vision for a film. I truly encourage anyone who loves movies and television to watch all that David produced. He was a true artist, through and through.”

Questlove wrote, “Lynch was the first human/creative that stressed the importance of not overworking and taking time out to breathe and meditate and searching for creative avenues not in my comfort zone.” Meanwhile, Flying Lotus posted “One of the world’s greatest artists of any era”.