Here’s a question: Is “immersion” the most valuable part of virtual reality?

The early days of VR’s (relatively recent) revival were characterized by attempts to highlight the things that differentiated it from other mediums. How it could function as “the ultimate empathy machine” according to Chris Milk, CEO of the recently Meta-acquired Within. Or how it realized the potential of science fiction’s vision of virtual worlds and the next evolution of the internet — a fact we still haven’t quite shaken.

Central to both ideas was the opinion that if you can make someone feel like they’re in a different place and able to take action there, they might become more engaged, productive, and happy. How we actually go about immersing ourselves in a virtual world has had to improve to make that feasible. Headsets are standalone now, like the Quest 2, and increasingly compact and lightweight, like the HTC Vive XR Elite. Input methods have been refined, from relying on existing console controllers to supporting hand and eye tracking. The one thing that hasn’t been settled is how we move around.

Should movement in VR be one-for-one? Do we need to track our legs at all? And how in the world should we go about doing it? These feel like the kind of questions that should be answered before VR becomes a mainstream form of computing. But doing so might reveal we’ve been focused on the wrong things all along.

The Leg Problem

The “Meta Legs Story” has now had multiple beats at this point, including a misleading press conference “demo” and a credible research paper outlining how the company could track leg movements with head-mounted cameras, but the problem starts with the general animosity many people feel towards Facebook and Instagram. Compound that with the general sense that Horizon Worlds hasn’t reached the visual fidelity people expected when Meta claimed it as an early pass at “the metaverse.” And then add on how easy it is to dunk on the company’s legless avatars and you’ve got a real crisis on your hands.

At the time, the issue really seemed to bother Meta (and perhaps specifically, CEO Mark Zuckerberg). On Instagram and Facebook, Zuckerberg shared a promised visual upgrade that would make environments more detailed and avatars slightly less dead-eyed. Then, at the company’s yearly Connect conference, he showed off legs and what seemed like leg tracking in VR to boot. That promised visual upgrade has yet to arrive, and after the fact, it was revealed that Meta faked leg tracking for the presentation using motion capture. The problem persists, but at least we got this tweet.

Even though Meta has decided not to address when legs will arrive on Quest devices, solutions do actually exist for full body tracking. HTC's recently updated Vive Trackers can be attached to just about anything and use cameras and inside-out tracking to work without the need for external Base Stations to track your location.

Solving the problem with existing hardware and software is difficult, if only because the main sensors of standalone VR headsets are so far away from your legs and feet. Meta’s researchers have been able to make some headway there too, though, attempting to simulate leg movement based on the position of your legs and arms.

When I asked analysts and devoted VR users whether they actually cared in the first place, most didn’t.

“Thing that [Meta’s Connect demo] reveals about the public obsession with legs in VR is that the people calling for it haven’t used VR,” Adario Strange, an analyst for Irreverent Labs and avid VR user, explained. Strange contends that full body tracking, and any attempts to simulate the experience of walking, aren’t really necessary to enjoy what’s compelling about VR.

Because most of the current ways of tracking your lower half require some kind of additional purchase or high-end gear, Anshel Sag, an analyst at Moore Insights & Strategy, speculates that “unfortunately it may end up becoming one of those things where it's like full body tracking is kind of a privilege… a digital divide.” I’m not sure full embodiment is as critical as say access to the internet or a computer, but the point stands. Not having legs could be a differentiator that matters to some.

Let’s Get Physical

So you manage to get legs in VR, whether they’re your own or some provided by the game, how are you going to move them? In my opinion, there is something inherently compelling about physically moving in VR. The exertion, even some simplified version, makes what you do in a game or app feel more real. It’s the same logic that made something like the motion controls of the Wii exciting. I might not know anything about sword fighting or be able to properly swing the weight of a real sword, but I feel like I’m doing something when I waggle the Wii Remote around in The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword. VR works just the same.

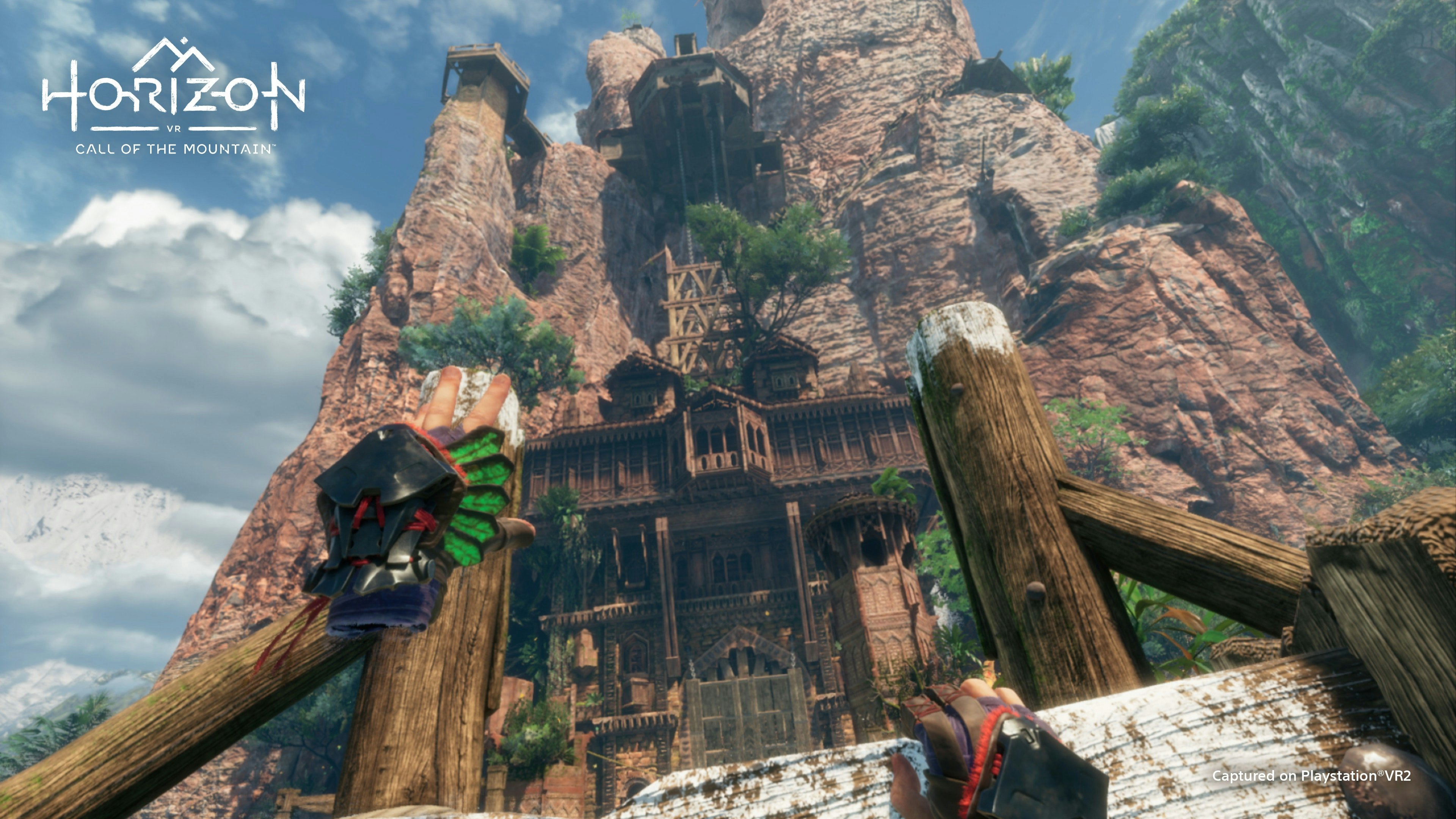

In a game like Horizon Call of the Mountain for the Playstation VR 2 walking, running, and climbing are all handled with arm waggling. When you’re working your way up a rock face, relying on just your hands makes sense if you don’t think about it too hard. Up and down arm movement to transition from a walk to a jog is less grounded in reality, but it at least matches what your arms might be doing when you’re moving your legs. The important part is (besides not excluding anyone who might not be able to stand to play) it feels like you’re doing a little more than just pointing and clicking a button.

“Ultimately, it's not what people imagined when they thought of VR. They don't imagine they're going to swing their arms just to move around,” Jan Goetgeluk, CEO of VR company Virtuix, told me over Zoom. “They don't imagine teleporting from A to B to C to D… no, they think about, ‘I just want to walk around inside the virtual world.’”

Virtuix’s Omni treadmill wasn’t designed for VR fitness applications, but burning calories ended up being an added benefit. “I hope it can save ourselves, somewhat, from our sedentary lifestyles,” Goetgeluk says. The Omni is one of the more complex VR accessories, but also one of the more interesting. By strapping yourself into a hinged arm (and your headset, of course) attached to a low friction, non-mechanical omni-directional treadmill, you can run, crouch, and walk in supported VR games. It requires a games developer to swap what would normally be a joystick input for your feet and leg movements, but after that, you’re able to get your steps in running in place.

A hardware solution isn’t going to be for everyone. The Omni is smaller than a traditional treadmill, but it still requires room and comes with a cost that might not be for everyone. Virtuix’s $2,595 Omni One is also really a package of the Omni and a Pico headset, meant for someone who’s looking to buy a complete VR system.

Being Somewhere Else

Is the sensation of walking, or even the presence of legs, worth all of that extra work? There’s got to be more to virtual reality than just moving around.

“The value add of VR is you can live in a small apartment in Hong Kong and have the whole world at your fingertips,” Strange says.

I think I agree. VR’s ability to create the sensation of being somewhere else, even only temporarily or partially, is far more interesting than its ability to do what the Wii or Kinect did.

Considering how little accommodations have been made for anyone who might not be able to see, stand, or hear but is still curious about a virtual or augmented reality experience, placing value outside of what we can purely simulate one-for-one seems like an important step too. You don’t need your legs, you need interesting things to do and interesting places to do them. As Strange told me, “most people just want more software.” Being fully embodied, immersed, whatever you want to call it, might not be as important as being fully engaged with what you’re doing. And you can do that, with or without legs.