“How good are novels!” So thinks protagonist Alice Fox in This Devastating Fever, the third novel from former publisher Sophie Cunningham. Alice is preparing to chair a panel at a writers’ festival, just as Covid-19 hits the headlines in March 2020.

The exclamation is slightly hysterical: do books and stories really matter when a deadly disease is sweeping the globe? Months later, in the grim, dark days of 2021, Alice’s worries are buttressed by a prize-winning author, who muses “maybe novel writing won’t even exist after the pandemic”.

Review: This Devastating Fever – Sophie Cunningham (Ultimo)

This Devastating Fever, Cunningham’s first novel since Bird (2008), is ostensibly about Leonard Woolf – the author, publisher and would-be politician most famous for being Virginia’s husband – and Alice, the writer who is attempting to craft a novel about him. Most importantly, though, it is a novel about novels, about their weight and worth in a complicated world.

Big ideas, but not a polemic

In recent years, the novel form has been forced to fight for legitimacy on multiple fronts. Against attention spans hobbled by (take your pick) social media, eco-anxiety or long Covid. Against the systematic defunding of the arts and humanities departments. Against suspicion that writing and reading fiction are particularly frivolous pursuits at a time of (take your pick) ecological collapse, economic downturn, war, pandemic and the decline of democracy. To all these concerns, This Devastating Fever is a powerful but finely drawn riposte.

I spend a significant portion of my time reading, teaching and thinking about novels. But I don’t think I’ve read a creative work quite this aware of so many contemporary conversations about what the form can and should be.

This Devastating Fever engages with the tricky relationship between fiction and non-fiction and the question of how literature engages with climate change. It also asks what it means to represent the past ethically, and what historical fiction might offer the future.

But for all its big ideas, This Devastating Fever is not a polemic or a tract: it is wry and clever and earnest – and yes, devastating when it needs to be. If the novel slips occasionally into a more essayistic mode, Cunningham is such an accomplished stylist that it is easy to forgive these lapses.

Cunningham proves that novels of ideas don’t need to be dour. This Devastating Fever is often very funny, as when Alice, irritated by her agent Sarah’s demand for more scintillating details of the Bloomsbury group’s infamous couplings, composes a dot point “SEX LIST or Who Fucked Who”, to which Sarah responds, via email, “it would be more grammatically correct to ask who fucked whom”.

Read more: Painting in circles and loving in triangles: the Bloomsbury Group's queer ways of seeing

An era of disasters

The novel is anchored by two interwoven narratives, neither told chronologically. It follows Leonard from 1904, the year he went as a very young man to then-Ceylon as a colonial administrator, to 1969 and his death. And it follows Alice, from when she begins the novel in 2004 (when Sri Lanka was devastated by the Indian Ocean tsunami) to her attempt to finish it in 2021, at the height of the pandemic.

Despite their many differences, Leonard and Alice are united in their sense that they are living, as Cunningham wrote in a 2020 essay, in an “era of disasters”, and a belief – sometimes faint but never fully surrendered – that there is meaning to be made by writing about, and in spite of, catastrophe.

Since 2016, when Amitav Ghosh declared the modern novel incapable of properly representing climate change, a wave of fiction has attempted to prove him wrong. This Devastating Fever joins a small but significant body of renovated historical fictions that range non-chronologically across time to show humans’ far-reaching impact on the earth.

Richard Powers won commercial and critical success with the form in The Overstory (2018). Bestselling writers Anthony Doerr (in Cloud Cuckoo Land, 2021) and Hanya Yanagihara (To Paradise, 2022) have attempted it. What makes Cunningham’s iteration different is that through Alice, who never stops feeling anxious about the legitimacy of her project and her capacity as a novelist, Cunningham lets us behind the curtain to see how the fiction gets made.

Autofiction and blurred lines

It is tempting to characterise the part of the novel focused on Alice – who is similar, but pointedly not identical to Cunningham – as autofiction, a term coined in the 1970s to describe certain French works that combined autobiographical and fictional elements. Today, autofiction sells well, while regularly attracting dissent.

Cunningham playfully evokes and denies the label. Readers are told that during her novel’s long gestation, Alice debates whether “Alice, who was, in one iteration of the manuscript, called ‘The Author’ should and could exist”. Cunningham reminds us that writers have always blurred the boundaries of fiction and non-fiction: Leonard Woolf’s The Wise Virgins (1914), a memoir masquerading as a novel, caused some distress to the friends and family he fictionalised.

Through Alice, Cunningham comments on the precariousness that comes of trying to live a creative life within our fragile arts ecosystem. But writing and reading remain as vital to Alice in the 2000s as they were to Leonard more than a century earlier.

This Devastating Fever is a love letter to the global writing fraternity – quotations from writers pepper the text – and to the archive; to the slow, good work of research, which becomes a way for Alice to (literally) speak with the dead. She is regularly visited by “Imaginary Leonard” and “Ghost Virginia”, who comment on the manuscript in progress.

The phenomenon of contemporary writers reanimating modernism’s major figures, methods and concerns (though few as playfully as Cunningham’s apparitions) is widespread enough for critics, including David James and Urmila Seshagiri, to call it “metamodernism”. Virginia Woolf in particular has generated experimental, hybrid fictions, like Michael Cunningham’s Pulitzer Prize-winning The Hours (1998) and Olivia Laing’s environmental memoir/biography To The River (2011).

Contemporary writers and artists of colour have returned to Woolf’s work, alert to the complexities of race and class it often omitted. Between 2009 and 2014, artist Kabe Wilson rearranged the 37,971 words of Woolf’s proto-feminist tract A Room of One’s Own (1929) to create “Of One Woman or So by Olivia N’Gowfri” (both the title and author name are anagrams of the originals). In this novella, a young, mixed-race Cambridge University student grapples with the invisibility of race and class in institutional and canonical literary studies.

Earlier this year, Michelle Cahill returned to Mrs Dalloway (1925) in Daisy and Woolf, exploring the undercurrents of race and imperialism in Woolf’s novel. Like Cunningham, she considers what it means to write and read ethically in contemporary life.

Read more: Friday essay: empathy or division? On the science and politics of storytelling

The Woolfs

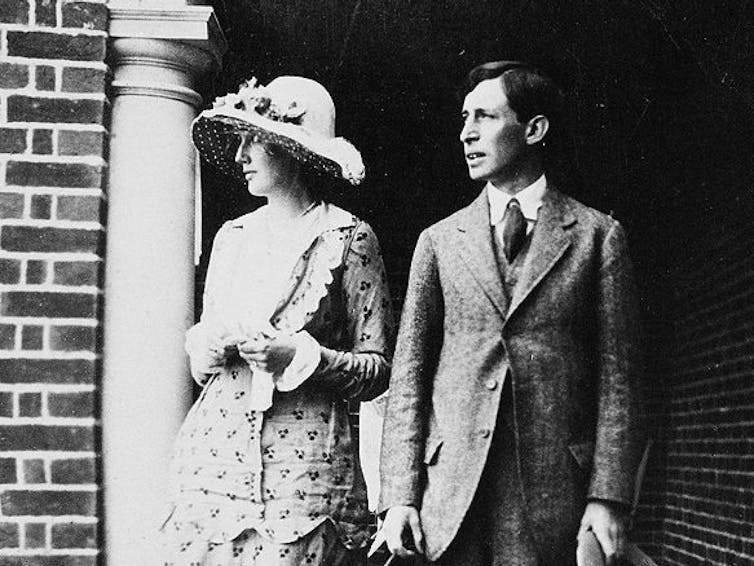

Virginia Woolf is a forceful presence in This Devastating Fever. Cunningham captures her racism and her snobbery, her trauma and her genius – and her dependence on the man who sometimes clumsily, but always valiantly nursed her and nurtured her creativity. It is this man, Leonard, who is the beating heart of the novel.

Cunningham works hard to neither romanticise nor demonise a man who “disliked fascists, gave apples to children, and liked leopards”, but also “once almost beat a horse to death and who tenaciously argued and truth-told until all around him were beaten or bored into submission”.

When we meet him, young Leonard is just realising the terrible absurdity of his role as a cog in the colonial machine. The novel neither forgives nor excuses his complicity. Cunningham connects the imperial project Leonard was involved in to the 1-in-6 inland vertebrates at risk of extinction in contemporary Sri Lanka, and with Australia’s detainment of the Nadesalingam family, which has only just come to an end.

One of my favourite pieces of recent non-fiction writing is Cunningham’s essay “The Age of Loneliness”, from her collection City of Trees (2019). It is about Ranee, the first elephant in Australia, and her long walk from Port Melbourne to the Royal Park Zoo in 1883. Even as Cunningham builds a larger theme about cruelty and loss in the Anthropocene, her portrait of Ranee is deeply felt and essentially true.

This Devastating Fever is full of similarly well-drawn animals: cats and a pandemic kitten, Bogong moths gathered around a light bulb, Leonard’s series of much-loved spaniels, a Marmoset named Mitz at whose death I shed actual tears. These animals are there to show the debt we owe to the non-human creatures whose planet we are destroying. In one scene, a diminishing number of flamingos rising from a lake take us forward from 1910 to 2005, their “flight feathers cutting through time” – but there is nothing instrumental about how they are written.

It is not always easy to write non-human beings into the very-human form of the novel, but Cunningham fits animals into her narrative like they fit in everyday life: with the rightness and naturalness of a pet curling up at one’s feet, or bees clustering around flowers in the front garden.

In many ways, Alice Fox and Leonard Wo(o)lf are of the same genus: they are both writers attempting to do their best by others, in the midst of what seems like the end of the world. Leonard’s role as a carer for Virginia is well-trodden but often misunderstood territory, which Cunningham writes with originality. It’s mirrored by the relationship between Alice and Hen, a beloved friend who unwillingly enters a nursing home with dementia.

Read more: If animals could speak, would we understand them?

Caring and what we owe

Caring, ultimately, is what this novel is about. It asks what caring means and explores how hard it can be to act with care in complicated circumstances. This Devastating Fever contains the joy and pain and terror of caring deeply for another living thing: whether a loved one whose mind is failing, or cicadas destined to be incinerated in the Black Summer fires. It is also about the need to read carefully, write carefully, and think carefully – about the past and how we respond to it, and about what we owe the dead, the living, and the future.

Leonard Woolf always claimed to live by the motto “nothing matters”, because in the great warp and weft of cosmological time, human beings are only a tiny blip. “It doesn’t matter,” his imaginary avatar says to Alice, about her novel. “We don’t matter. Nothing really does.”

In line with this sentiment, Alice never really reconciles the anxiety she feels over her project, and Cunningham offers no grand affirmation of the power and purpose of the novel form. But a good novel – and This Devastating Fever is a very good novel – doesn’t need to justify its existence so directly. The reader already knows.

“We can’t save them, can we?” Alice asks Imaginary Leonard at one point. Her question is ostensibly about Virginia and Hen, but could just as feasibly be about animals, reading and writing, the earth. Leonard doesn’t reply, but Cunningham’s novel answers for him: maybe not, but there is infinite grace in the trying.

Meg Brayshaw does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.