Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a peerless exhibition of Aboriginal art, thrilling in its breadth and depth.

Seven years in the planning, now showing at the National Museum of Australia, it sets a standard that must be emulated elsewhere if the greater Australian population is to move beyond stereotypical truisms about Aboriginal narrative traditions, concepts and artefacts, which view these as simple or inferior to those of other world cultural traditions.

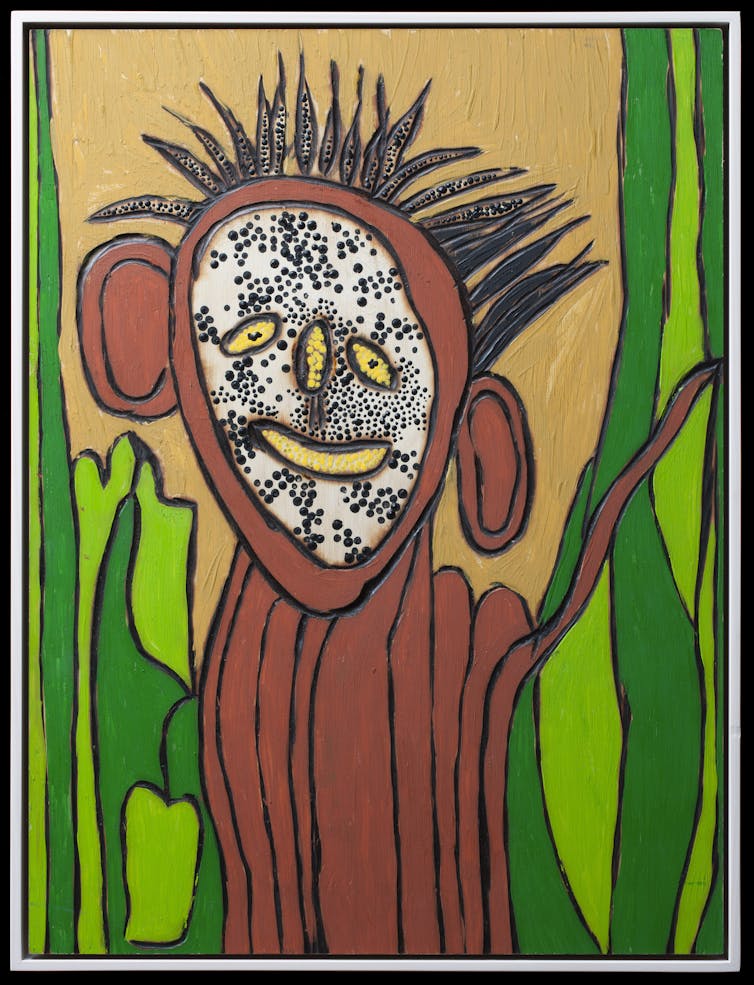

Songlines sets out to portray one of the most defining and predominant meta-narratives chronicled in ancient mainland Australia - the story of a predatory, lascivious, rejected loner - an Ancestral Being initially in the guise of a man - who relentlessly pursues seven sisters (Ancestral Women) over land and sky.

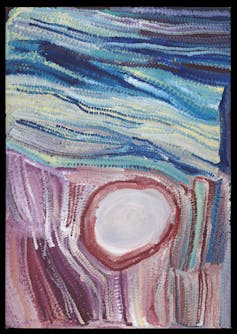

In the exhibition, this repetitive, circular journey begins in Martu country in the west (the Pilbara region). In hot pursuit, the man travels east, crossing the Ngaanyatjarra lands in WA and the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjara country on the APY (Anangu Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjara) lands in South Australia. By this time, the seven sisters have become stars, the star cluster known by the Ancient Greeks as the Pleiades. (Subsequently, the man takes the form of Orion’s Belt).

Not portrayed in this exhibition is the protagonists’ further cross-country travel, for example into Warlpiri country, where the seven sisters become the Napaljarri-warnu and their pursuer, in one of his shape-shifting iterations, a Wardilyka (Bush Turkey).

The exhibition is cleverly organised so that viewers walk the same route through the gallery spaces and traverse the same Aboriginal lands as these Ancestral Beings who “footwalked” (to use Warlpiri Aboriginal English) the country or flew over it. It includes an extraordinary Digital DomeLab, where the viewer lies on her/his back and watches the action taking place in the sky with 360 degree vision.

In undertaking this journey, one becomes integral to the exhibition. The viewer is bathed in the visual, the auditory (including meticulously choreographed vocalisation and sonic pulse waves), and immersed in affective, multimedia modes of knowledge.

A six-hour experience

Like many other exhibition-goers, I spent six hours exploring it, during which time my attention did not once falter. It is an intense educative experience. Making the journey on foot (or by wheelchair), enables viewers to understand changes in terrain, in localised flora and fauna, and differences in types of water sources.

And, as one crosses country, it is evident that there are also changes in language use - for example, the lustful sorcerer is initially named Yurla, but later, as he moves eastwards into different country, he is called Wati Nyiru (“The Man Nyiru”).

When on Martu country, where the seven sisters take humanoid form and live on the ground, they’re known as “Minyipuru”. As they travel further east and decide to fly through the sky to escape their lustful pursuer (and at times avoid country belonging to others), they switch languages and become known as the “Kungkarangkalpa”. New and gripping episodes in this lengthy saga come into being as the pursuit, escape and journey unfold.

The man’s sorcery skills mean that he tries every trick in the book to have his wicked way with the women, particularly targeting the eldest sister, on whom he’s fixated. Like all Aboriginal sorcery figures (and indeed Ancestor Beings more generally), the man has the capacity to shift shape, transforming himself to lure his “prey” into coming closer to him. In various guises – as an edible snake, or a shady tree, or as temptingly delicious fruit - he devises strategy after strategy to bring the women under his control.

But the women too have the ability to change shape and form, so on occasion they become rocks, trees or flowers to avoid his unwanted advances. Although he succeeds once in hoodwinking and brutalising the eldest sister, causing her to become dreadfully ill, ultimately the sisters, in a convincing and intelligent expression of familial and female solidarity, outwit their antagonist.

There is also wicked humour in this saga. When the sisters decide to take to the sky from a site called Pangkal, they hover directly over the sorcerer Yurla, who’s watching from ground level. The sisters, in a spontaneous outburst of collective naughtiness, decide to “flash” - to expose their genitals - for the sole purpose of taunting Yurla.

The sisters’ inability to resist this delicious touch of Schadenfreude in this deliberately provocative “bye-bye, and fuck you!” parting gesture provides some light comic relief. Not long after, in the next episode of the saga, the enraged sorcerer ups the ante in terms of his obsessional (“If I can’t have you, then I will destroy you”) “love” for the sisters.

What sets this exhibition apart

In my view, there are several factors that set Songlines apart from the hundreds, if not thousands, of Australian and international Aboriginal art exhibitions that I’ve visited over the years.

This was not the bright idea of a curator born and bred in the city but rather a proposal from the Anangu people of the APY Lands. They directly approached ANU and the museum with the idea of preserving this Tjukurpa (“Dreaming”). Their move was underpinned by the older people’s concern about the possibility of the total loss of this “songline” as it’s described in the exhibition title.

In this respect, the more usual “top-down” approach was not taken but rather, the exhibition resulted from the direct intervention of Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjara people. They saw this as part of a broader strategy to hang on to their culture and language, and to inspire current and future generations.

Related to this is the fact that the curatorial group comprised both Anangu and Yanangu men and women (the true knowledge-holders) along with museum curators, academics and others. This did not adhere to the usual hierarchical model whereby a senior curator is almost always the head honcho in terms of selection of works, directing research, and organising the layout and “hang” of an exhibition.

The knowledge bearers stressed that they wished to share this knowledge with all Australians as mutual legacy.

Putting aside certain of the larger state and national galleries and well-funded private galleries, classical Australian Aboriginal art is often exhibited in ways that entirely unmoor the artworks from their original contexts. For example, such exhibitions tend to homogenise specific botanical species on display under the generic and primitivist tagline of “bush tucker”, often providing little or no acknowledgement of the exponentially greater complexity of Aboriginal knowledge systems in which these works are grounded.

While there have been recent encouraging moves toward reflecting the complexities of Indigenous cognition, epistemology and metaphysics, the long lead-up time to this exhibition has paid real dividends in terms of contextualising it.

Aboriginal art was the original and first form of “performance art”, comprising visual art, dance, music and song, narrative and poetry. This is the first time I have seen all of these art forms integrated into a single exhibition. In addition, the movement between gallery spaces opens up portals to knowledge and understanding in ways that will force many people to question any prior knowledge they have believed (often without foundation) about Aboriginal artistic and narrative practice.

The auditory mode is often overlooked in exhibitions, but vocalisation and sonic communication play an essential role in this one.

Finally, the use of new multimedia technologies in museums and galleries can often seem to be simply bells and whistles, an add-on to a sometimes otherwise dreary show. But here, such technology acts as an enabler, allowing the viewer to get closer to the intention and meaning of the exhibition.

An authentic Australian narrative

Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is founded on a narrative that makes the mythology of the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians seem ultra-recent. At the same time, it is a story relevant to our times, resonating with events leading up to the #MeToo movement, and similar controversies in Australia and beyond. In this regard it has something to offer all human beings, regardless of ethnicity, gender or political affiliation. Its universal application is something it holds in common with all the world’s greatest narratives, from the Ramayana to the Odyssey.

And it relates to an authentically Australian narrative that is equally or more engaging than any other epic tale you’ll have experienced. It will rearrange the furniture in your head by opening up new portals to knowledge and understanding.

Songlines is at the National Museum in Canberra until February 25.

Christine Judith Nicholls does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.