On an April day under a cloudy sky earlier this year, professional yachtsman Russ Fairman embarked on a 2,400-mile circumnavigation of the British Isles. Departing Southampton on a 34-foot yacht christened Mintaka, Fairman sailed anti-clockwise in what he described as “a prayer hug around Britain”.

The voyage took in important Christian destinations, including Walsingham, Lindisfarne and Iona, in aid of the Catholic seafarers’ charity, Stella Maris. On July 9 – Sea Sunday, a Catholic feast day of prayers for seagoers and fishermen – Mintaka arrived in Portsmouth, after 70 days at sea.

From Iraq and Mexico to India and Belgium, the numbers of people recorded at pilgrim destinations – Christian, Muslim and beyond – are hitting record highs.

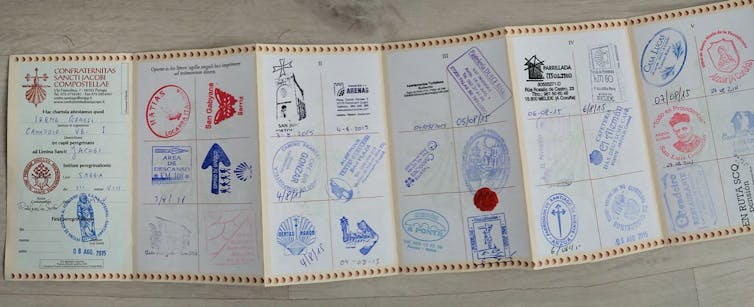

In 2022, the Camino de Santiago in northern Spain saw 438,307 pilgrims collecting their compostelas (certificates of completion). Most people do the Camino on foot. But pedestrian travel isn’t the only way of getting to a shrine.

Many choose to make pilgrimages by bike or motorcycle, by truck and tractor, by donkey, on horseback – and, like Fairman, by boat.

Sailing pilgrimages are now recognised by the Camino de Santiago authorities, with the numbers choosing to sail almost doubling since 2019, from 243 to 448 in 2022.

I have researched how the idea of the pilgrimage – in Christian and post-Christian societies – is changing. Water-borne transport is championed as a sustainable option. As part of what tourism experts term “slow travel”, it is becoming ever more important for modern pilgrims searching for spirituality in creative ways. I am a sailor myself. There is something special, even otherworldly, about time spent at sea.

What sea travel offers pilgrims that land travel doesn’t

Literary voyages suggest that sea travel is rich in spiritual symbolism. The Voyage of St Brendan is a case in point. Supposedly undertaken by the sixth-century Irish monk, St Brendan of Clonfert, this legendary island-hopping journey was replicated by the British explorer Timothy Severin in the mid 1970s.

A sea passage can be a liminal experience. Shore life is temporarily held in suspension. Space is made for soul-searching and reflection. There’s respite from the stresses of everyday life. As Fairman told me by email: “True life for me exists at boundaries, where one world meets another, heaven touches earth, the spiritual interacts with the physical.”

There is also the sheer exhilaration of being immersed in a truly wild, natural environment. One of Fairman’s volunteer crew members put it plainly in a personal testimony recorded for a thanksgiving prayer night at the end of their voyage: “It was beautiful to be out in the elements of sea and wind where God’s creation was so much bigger than our man-made world.”

This chimes with research highlighting the health and spiritual benefits of time spent in nature. The faith tourism scholar Veena Sharma writes that the pilgrim’s journey is a process of opening up to the forces of nature: “The pilgrim mind reveres the path, the woods, rivers and the empty spaces.”

The long history of maritime pilgrimages

Local pilgrimages attest to the continued beliefs and religious practices of coastal communities in France, Spain, Brazil and the Adriatic.

Sea travel was key to the spread of early Christianity. Fairman was inspired by the Celtic missionary saints and, in particular, St Columba of Iona, the Irish monk credited with evangelising the land now known as Scotland and founding the abbey on Iona. And the earliest Christian pilgrims travelled to sacred destinations, such as the Holy Land, by boat.

By the 1300s, English pilgrims found the direct maritime route to Santiago de Compostela to be more expedient than traversing mainland Europe as many people still do today, by foot, along the Camino Francés, the French Way. People would instead depart from Southampton, Bristol and other southern ports, and sail to La Corũna in Spain, to join the route now known as the Camino Inglés – the English Way. From here they walked the last stretch to Santiago.

Contemporary maritime pilgrimages like Fairman’s attest to rising interest in connecting to that long, holy history. And you don’t necessarily need sailing experience to get involved.

How to get involved

Several newly established pilgrimage routes cross maritime borders. The Wexford-Pembrokeshire Pilgrimage Way, launched in 2023, links Ireland and Wales. And St Sigrid’s Way, from York to Sweden, crosses the North Sea. The St Olav Waterway, established in 2019, sees pilgrims island hop from Sweden to Norway by ferry, kayak or chartered boat.

Pilgrimage tours by ferry or charter take visitors to holy islands including Iona in Scotland, Bardsey Island in Wales, Caldey Island in Pembrokeshire and Flat Holme in the English Channel.

It is also now possible to join the Camino de Santiago from the UK, via the St James Way, which takes pilgrims from Reading to Southampton. They then make their way across the English Channel to continue their journey to Santiago de Compostela through France and Spain. In June 2024, I will join the UK Confraternity of St James’s Tall-Ship Camino departing from Fowey in Cornwall, disembarking at La Corũna in Spain. Sailors of all abilities are welcome.

For the last eight years, the North Marinas Association has organised an annual Camino a Vela (which translates as “camino by sail”). This flotilla of up to 30 sailing boats comprises crews of people from across the world, including novice recruits.

Throughout the ages, seascapes have been used as the backdrop for spiritual encounters. Today, seasoned sailors well atuned to the power of nature still relay miraculous occurrences at sea.

Poised between one landmass and the next, you are vulnerable to the elements, truly “betwixt and between”, as cultural anthropologist Victor Turner puts it in his 1967 book of essays, The Forest of Symbols. At sea, to Fairman’s mind, is where pilgrimage comes into its own: “This is where one grows and discovers the depth of our own being, and who we really are.”

Anne Bailey does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.