Tarek Mansour spent several years working in finance at firms like Goldman Sachs and Citadel before launching the groundbreaking fintech startup Kalshi. Using his background in finance, he built the first regulated exchange, running what are called “event contracts” or ways to trade on current affairs like national elections.

With the upcoming 2024 United States presidential election, increasingly razor-thin Republican control in the House of Representatives and the contentious GOP primaries, Kalshi and platforms like it – including PredictIt, Polymarket and Smarkets – are in the spotlight for allowing financial bets that critics worry could sway voters.

Event contracts are comparable to trading on the stock market. Like the speculative nature of Kalshi’s offerings, its product is more closely aligned with commodity trading – hedging on the future price of oil, natural gas, wheat or coal.

“We focus on events that are of economic and social value,” Mansour told Al Jazeera.

Like trading on the stock market, a given company’s share price could rise and fall based on current events. For instance, if there is an escalation in COVID-19 cases, Moderna’s stock could be affected.

But Kalshi allows consumers to trade event contracts on COVID-19 itself.

Mansour says that trading on events in a speculative nature is comparable to insurance.

There are also event contracts on Kalshi that allow users to wager on the likelihood of natural disasters. There are, for instance, two listings on its homepage for disasters hitting cities like Columbus in Ohio and Houston in Texas – the fourth-most-populous city in the US, which was decimated by Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

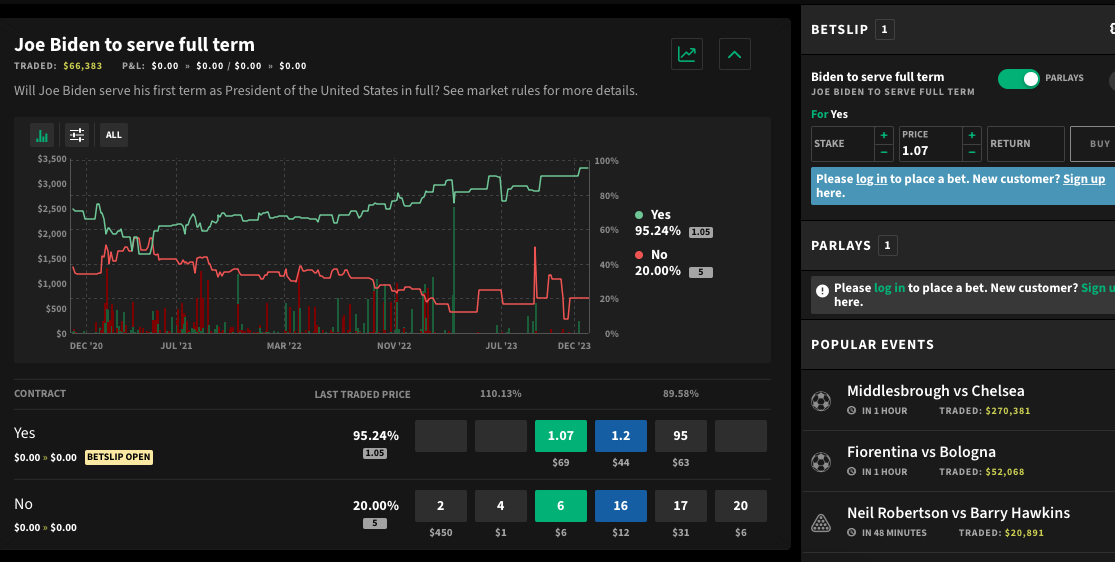

Individual event contracts on Kalshi are less than a dollar but that can really vary across the sector. On Smarkets for example, as of January 9, the last traded minimum price on [US President] “Joe Biden to serve full term” was $1.05. Across the sector, there is nothing stopping users from buying a lot of that, much like they would for shares in a company.

Proponents argue this is no different than insurance companies factoring in whether or not to provide flood insurance to a home.

In the last year alone, several insurance companies including Farmers announced they will no longer offer flood insurance to Florida homeowners because of the increased risks of climate change.

“There are all these commercial and financial risk management needs out there that financial markets over time accommodate,” said lawyer Robert Zwirb, who served as the counsel for two former chairpersons of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC).

“Things that are considered revolutionary today, in 30 years won’t be,” Zwirb added.

Not everyone thinks predictive betting is a good thing, especially when it comes to elections. Ahead of the 2024 election cycle, there are serious concerns about the precedent it sets.

Last year, Kalshi requested approval to trade contracts during elections. The backlash that followed was primarily from progressives.

Several Democratic senators feel the same way. Senators Chris Van Hollen (Maryland), Jeff Merkley (Oregon) Sheldon Whitehouse (Rhode Island), Ed Markey (Massachussetts), Elizabeth Warren (Massachusetts), and the late Dianne Feinstein (California) – all Democrats – called on the CFTC to reject Kalshi’s proposal.

In an August release, the group of senators said: “There is no doubt that the mass commodification of our democratic process would raise widespread concerns about the integrity of our electoral process. Such an outcome is in clear conflict with the public interest and would undermine confidence in our political process – we urge the CFTC to deny Kalshi’s proposal.”

‘Financial incentive to voting’

“Electoral betting is really dangerous because it makes a huge financial incentive to voting,” said Sydney Bryant, the author of a piece calling out Kalshi last year for the Center for American Progress.

While election betting is frowned upon in the US, it is allowed under specific circumstances. Companies like Kalshi have made efforts to move the goalposts.

“This isn’t the Kentucky Derby. Our Democracy is not a stakes race,” Bryant added.

The CFTC shared those concerns and rejected Kalshi’s proposal in September. The agency said: “The contracts would have been cash-settled, binary contracts based on the question: Will <chamber of Congress> be controlled by <party> for <term>?” which is “contrary to the public interest”.

There were more than 1,300 public comments on the matter. Many of them echoed the think tank and the group of progressive senators.

Jennifer Venar, one of the public commenters, wrote: “Allowing bets to be placed on the outcome of elections is a truly horrendous idea. At best it further delegitimize[s] the voting process by making it a game and at worst, it encourages further tampering in elections. Please! Do no[t] do this.”

Another commenter, named Ken Bell said:

“This is absolutely insane. It would greatly contribute to the continued deterioration of our tenuously held democracy by encouraging and rewarding intervention in the political process for monetary gain.”

In November, Kalshi filed a lawsuit challenging the agency’s decision.

For now, Kalshi will not trade on individual congressional races, which can often come down to slim margins.

“We are not looking through the small congressional elections; we are looking at who is going to control the House or the Senate,” Mansour says.

Slim margins a deciding vote

But a small congressional race could very well be the deciding factor for who controls the US House of Representatives. That’s thanks to several recent changes in the House, including the expulsion of controversial member George Santos amid a scathing ethics report that found several alleged campaign finance violations.

Kevin McCarthy, who was removed as House speaker, announced he would also leave Congress, making Republicans’ already razor-thin majority that much more vulnerable.

There were several congressional races in 2020 with very slim margins. Such races, argue experts including Tom Moore, a senior fellow at the Center For American Progress, have the power to affect elections for financial gain.

“With a House this tight, every race is big,” Moore told Al Jazeera.

Amid increased polarisation, tight margins, he believes, have the power to potentially sway a close election. In the last election cycle, for instance, far-right Republican Lauren Boebert won her US congressional district in Colorado by a mere 546 votes.

“When citizens vote, their task is to vote for who they think should win the election. But if they have money riding on it, they will be incentivised to vote [for] who they think will win the election. That changes the nature of that vote,” Moore told Al Jazeera.

This isn’t the first time platform event-prediction markets popped up in the US and met with substantial opposition. In 2003, the Pentagon had plans for a comparable platform that allowed trading on political turmoil in the Middle East. The Pentagon quickly scrapped the programme amid pressure from Senate Democrats at the time.

Now Kalshi is one of the latest to face scrutiny from regulators but it is far from alone. In the last few years, the CFTC has cracked down on several platforms that offer event contracts.

PredictIt is one that has been accused of skirting regulations in the past.

In August 2022, the CFTC called for PredictIt to cease operations within six months. This was because it allegedly did not comply with a 2014 no-action letter from the agency, which did allow political and economic trades but only if they were for “academic research purposes” and carried out by a university faculty.

A letter from the CFTC pointed out that Aristotle International, Inc – a private company – operated the market rather than a university faculty.

The letter also accused PredictIt of trading on event contracts outside the scope of politics and economics, such as “Whether the WHO [World Health Organization] will declare COVID-19 to be a ‘pandemic’ before March 6 2020?” or “How many Ebola cases in the U.S. in 2015?”

PredictIt fought back and was ultimately successful. The platform is still running, although its operations are much smaller in scale. On its website, you can trade shares on who will win the Republican Iowa caucuses or the New Hampshire primary election.

“It’s a vibrant, important information-decimating tool with institutions and individual traders on PredictIt who understand that markets have forecasting ability,” says the company’s CEO John Phillips.

PredictIt says its trading platform is a more reliable indicator of public polling.

The CFTC also went after Polymarket, which allows betting on US elections and much more. As of January 9, there are bids on political events ranging from congressional races in California as well as the outcome of the November election.

The platform also allows betting on whether there will be a new global pandemic by February 1, and on the outcomes of several consequential geopolitical conflicts including those in Gaza and Ukraine.

Polymarket is “viewer only” for US consumers after pushback from the CFTC. In 2022, the exchange was fined $1.4m after it failed to obtain the proper registrations.

UK-based Smarkets also allows trading on US elections. Primarily focused on sports betting and United Kingdom politics, it has expanded in the US in recent years.

But consumers can still bet on several political topics stateside, including the outcome of the Iowa caucuses, whether Biden will be re-elected in November and even some Supreme Court cases.

However, in October, Smarkets CEO Jason Trost announced the company would pause further expansion without explaining why and that trading is not available to US-based consumers.

The CFTC’s crackdown comes amid increased concerns about the safety and security of US elections.

While Donald Trump’s own national security officials said the 2020 election that he lost to Biden was the most secure in US history, the former president and staunch allies like Arizona’s Kari Lake still assert, without evidence, that the election was stolen – a move that only fuelled distrust for the electoral process among Trump’s far-right base.

Now, as Trump, the Republican frontrunner, will likely face off against incumbent Biden in November, faith in elections is at record lows. Even before Trump’s unfounded claims about a “stolen” election, only 59 percent of US voters trusted the accuracy of the country’s elections, according to Gallup.

According to an AP-NORC poll from last year, only 22 percent of Republicans and 71 percent of Democrats trust the integrity of US elections.

Despite the wave of criticism, Mansour does not believe his product will affect an election’s outcome. He believes that it provides an additional tool to properly forecast how elections will unfold.

“These markets are not about swaying votes,” he said, “but about forecasting what’s going to happen”.