K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil knew his history.

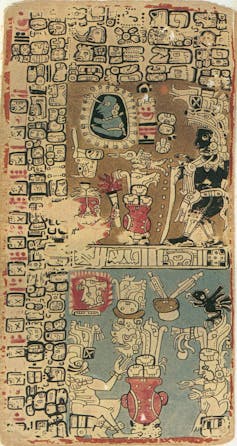

For 11 generations, the Mayan ruler’s dynasty had ruled Copan, a city-state near today’s border between Honduras and Guatemala. From the fifth century C.E. into the seventh century, scribes painted his ancestors’ genealogies into manuscripts and carved them in stone monuments throughout the city.

Around 650, one particular piece of architectural history appears to have caught his eye.

Centuries before, village masons built special structures for public ceremonies to view the Sun – ceremonies that were temporally anchored to the solstices, like the one that will occur June 20, 2024. Building these types of architectural complexes, which archaeologists call “E-Groups,” had largely fallen out of fashion by K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil’s time.

But aiming to realize his ambitious plans for his city, he seems to have found inspiration in these astronomical public spaces, as I’ve written about in my research on ancient Mayan hieroglyphically recorded astronomy.

K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil’s innovations are a reminder that science changes through discovery or invention – but also occasionally for personal or political purposes, particularly in the ancient world.

Viewing the horizon

E-Groups were first constructed in the Mayan region as early as 1000 B.C.E. The site of Ceibal, on the banks of the Pasión River in central Guatemala, is one such example. There, residents built a long, plastered platform bordering the eastern edge of a large plaza. Three structures were arranged along a north-south axis atop this platform, with roofs tall enough to rise above the rainforest floral canopy.

Within the center of the plaza, to the west of the platform, they built a radially symmetric pyramid. From there, observers could follow sunrise behind and between the structures on the platform over the course of the year.

At one level, the earliest E-Group complexes served very practical purposes. In Preclassic villages where these complexes have been found, like Ceibal, populations of several hundred to a few thousand lived on “milpa” or “slash-and-burn” farming techniques practices still maintained in pueblos throughout Mesoamerica today. Farmers chop down brush vegetation, then burn it to fertilize the soil. This requires careful attention to the rainy season, which was tracked in ancient times by following the position of the rising Sun at the horizon.

Most of the sites in the Classic Mayan heartland, however, are located in flat, forested landscapes with few notable features along the horizon. Only a green sea of the floral canopy meets the eye of an observer standing on a tall pyramid.

By punctuating the horizon, the eastern structures of E-Group complexes could be used to mark the solar extremes. Sunrise behind the northernmost structure of the eastern platform would be observed on the summer solstice. Sunrise behind the southernmost structure marked the winter solstice. The equinoxes could be marked halfway between, when the Sun rose due east.

Scholars are still debating key factors of these complexes, but their religious significance is well attested. Caches of finely worked jade and ritual pottery reflect a cosmology oriented around the four cardinal directions, which may have coordinated with the E-Group’s division of the year.

Fading knowledge

K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil’s citizenry, however, would have been less attuned to direct celestial observations than their ancestors.

By the seventh century, Mayan political organization had changed significantly. Copan had grown to as many as 25,000 residents, and agricultural technologies also changed to keep up. Cities of the Classic period practiced multiple forms of intensive agriculture that relied on sophisticated water management strategies, buffering the need to meticulously follow the horizon movement of the Sun.

E-Group complexes continued to be built into the Classic period, but they were no longer oriented to sunrise, and they served political or stylistic purposes rather than celestial views.

Such a development, I think, resonates today. People pay attention to the changing of the seasons, and they know when the summer solstice occurs thanks to a calendar app on their phones. But they probably don’t remember the science: how the tilt of the Earth and its path around the Sun make it appear as though the Sun itself travels north or south along the eastern horizon.

United through ritual

During the mid-seventh century, K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil had developed ambitious plans for his city – and astronomy provided one opportunity to help achieve them.

He is known today for his extravagant burial chamber, exemplifying the success he eventually achieved. This tomb is located in the heart of a magnificent structure, fronted by the “Hieroglyphic Stairway”: a record of his dynasty’s history that is one of the largest single inscriptions in ancient history.

Eying opportunities to transform Copan into a regional power, K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil looked for alliances beyond his local nobility, and he reached out to nearby villages.

Over the past century, several scholars, including me, have investigated the astronomical component to his plan. It appears that K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil commissioned a set of stone monuments or “stelae,” positioned within the city and in the foothills of the Copan Valley, which tracked the Sun along the horizon.

Like E-Group complexes, these monuments engaged the public in solar observations. Taken together, the stelae created a countdown to an important calendric event, orchestrated by the Sun.

Back in the 1920s, archaeologist Sylvanus Morley noted that from Stela 12, to the east of the city, one could witness the Sun set behind Stela 10, on a foothill to the west, twice each year. Half a century later, archaeoastronomer Anthony Aveni recognized that these two sunsets defined 20-day intervals relative to the equinoxes and the zenith passage of the Sun, when shadows of vertical objects disappear. Twenty days is an important interval in the Mayan calendar and corresponds to the length of a “month” in the solar year.

My own research showed that the dates on several stelae also commemorate some of these 20-day interval events. In addition, they all lead up to a once-every-20-year event called a “katun end.”

K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil celebrated this katun end, setting his plans for regional hegemony in motion at Quirigua, a growing, influential city some 30 miles away. A round altar there carries an image of him, commemorating his arrival. The hieroglyphic text tells us that K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil “danced” at Quirigua, cementing an alliance between the two cities.

In other words, K’ahk’ Uti’ Witz’ K’awiil’s “solar stelae” did more than track the Sun. The monuments brought communities together to witness astronomical events for shared cultural and religious experiences, reaching across generations.

Coming together to appreciate the natural cycles that make life on Earth possible is something that – I hope – will never fade with fashion.

Gerardo Aldana does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.