Only a third of books translated into English are by women authors. August is Women in Translation month, which hopes to address this imbalance by getting more people reading and buying – and publishers translating – books by women. In a bid to do our part we asked a few of our experts to recommend some of their favourite books.

This is by no means an exhaustive list, but a starting point for you to go and discover more wonderful books by women from all over the world that have been translated into English.

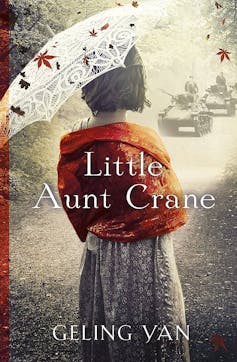

1. Little Aunt Crane by Yan Geling, translated from Chinese by Esther Tyldesley

Little Aunt Crane shocks readers with its powerful opening. The second world war is ending and the Japanese have surrendered. The village of Sakito in north-eastern China is full of Japanese nationals and as the Chinese draw in, the elders decide to preserve their honour. The villagers embark on a mass suicide. There is only one survivor, 16-year-old Tatsuru.

Tatsuru, alone and in a country hostile to Japanese people, attempts to flee but is captured by human traffickers and sold to a wealthy Chinese family looking for a surrogate. Her name is changed to Duohe and she is told she must bear the children of their son while pretending to be the sister of his wife, Xiaohuan. An unlikely bond develops between the two women in this story that spans several decades of Mao’s rule.

Little Aunt Crane is a powerful novel about identity, love and family that also manages to trace the intricate emotional, ethical and even political challenges in post-war China. It’s a rare example of a Chinese novel that focuses on a Japanese protagonist in the post-war era, highlighting the struggles of women like Duohe and Xiaohuan.

Reviewed by Beixi Li

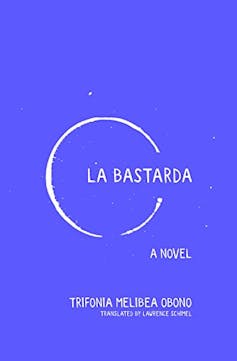

2. La Bastarda, by Trifonia Melibea Obono, translated from Spanish by Lawrence Schimel

“Come on, try it. You’ll like it. You’re in the forest – the Fang forest is a free space. Now you’re free.” Freedom is not something orphaned narrator Okomo is accustomed to. Which makes this particular scene of queer sexual desire – away from the heterosexual, patriarchal traditions of the village – all the more exhilarating. Okomo’s family belong to the Fang community, the largest ethnic group in mainland Equatorial Guinea.

This short, sharp, addictive novel follows Okomo as she decodes and navigates the restrictive norms of Fang culture and searches for her estranged father. The narrative is laden with rules and hierarchies that structure Okomo’s existence and the characters around her are distinguished by their position, their relationships and their achievements.

Yet Trifonia Melibea Obono – and Lawrence Schimel, through his translation from Spanish – draw us to those who do not fit within these hierarchies. In these relationships between outcasts there is sanctuary to be found, away from the structural and physical violence, away in the shelter of the forest.

Reviewed by Olivia Hellewell

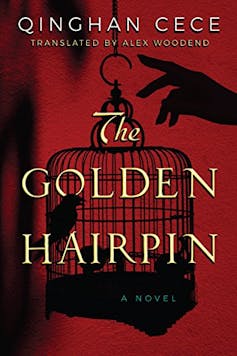

3. The Golden Hairpin by Cece Qinghan, translated from Chinese by Alex Woodend

The Golden Hairpin is a historical crime novel set during the reign of Emperor Yizong of Tang (AD859 to AD873) of China. The main character, Huang Zixia, is accused of murder. She disguises herself as a boy and infiltrates the palace to try to clear her name.

Huang Zixia finds herself caught up in mysteries, which must be solved against a background of treacherous court battles and intrigue. In China, Huang Zixia’s hairpin is as iconic as Sherlock Holmes’s deerstalker hat and pipe and she is an intelligent and courageous female sleuth.

If you are interested in Chinese culture, especially the Tang Dynasty, you will love this beautifully written and intricately plotted novel.

Reviewed by Beixi Li

4. Take Six: Six Balkan Women Writers, translated from Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian and Macdeonian by Will Firth, and Slovenian by Olivia Hellewell

Anthologies can be tricky things and grouping writers together by arbitrary labels is not without its problems. But this anthology, which brings us six writers from six countries that were part of Yugoslavia until the early 1990s, is an excellent example of what a good anthology can do.

As one of its translators, I am biased, but this collection showcases a variety of forms and styles and provides the opportunity to dip in and discover writing that is not otherwise easy to come by in English translation.

Under one cover, readers can find autobiographical pieces, little-heard accounts of women’s lives in rural Bosnia, meandering travel prose, a genre-defying polyphonic story about time and space and stories connected by small objects or by settings. As a translator of the Slovenian stories, I am especially fond of the humour that Ana Svetel’s stories inject into the collection.

Reviewed by Olivia Hellewell

5. The Blue Book of Nebo, written and translated from Welsh by Manon Steffan Ros

Told as a series of diary entries, The Blue Book of Nebo is a moving tale of a mother-son relationship after an unspecified apocalypse devastates the UK. Rowenna and her teenage son Dylan survive alone in their Welsh village, growing their own food and raiding nearby houses for tools and books.

The book is a knowing take on the young adult post-apocalypse novel. It reminded me, in the best way, of nuclear novels like Louise Lawrence’s Children of the Dust (1985) or Gudrun Pausewang’s The Last Children of Schewenborn (1983).

Manon Steffan Ros usually writes in Welsh. The English version is a beautiful reflection on reclaiming the Welsh language – an aspect of the novel which was, intriguingly, introduced in translation. Last year the novel became the first ever translated book to win the Yoto Carnegie Medal for children’s literature.

Reviewed by Carol O'Sullivan

6. As We Exist: A Postcolonial Autobiography by Harchi Kaoutar, translated from French by Harchi Kaoutar and Emma Ramadan

Harchi’s literary memoir retraces the author and sociologist’s formative years in eastern France. Born in a loving, hardworking family from the Moroccan diaspora, Harchi dispels the myth of a multicultural France to capture the injustices of a society where “the figure of the Muslim embodies the myth of the enemy within”.

Harchi describes various forms of sanctioned violence imposed on post-colonial citizens that fall under the banner of state racism, including marginalising women and banning religious symbols from state schools. Harchi’s elegant prose recalls the fear experienced within many communities when the death of two teenagers fleeing from the police led to three weeks of violent riots against police brutality and increased cultural divisions in 2005.

Written in powerful poetic language, Harchi’s book eloquently describes how growing up as an outsider shaped her identity and awakened her political awareness. This timely translation provides a pertinent insight into contemporary French society.

Reviewed by Nicole Fayard

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

nicole.fayard@le.ac.uk has previously received funding from the British Academy. Affiliations: Chair of Leicester Freeva; member of the Executive Board of the ASMCF (no financial interest in either) and member of staff at the University of Leicester (no financial gain).

Beixi Li, Carol O'Sullivan, and Olivia Hellewell do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.