Last month, Singapore’s former manpower minister Josephine Teo said that the Singapore People’s Action Party (PAP) government is “pro-worker.”

The data shows otherwise.

If the PAP government is “pro-worker,” workers will be given adequate wages and protections. But Singapore’s low-income workers earn even less than the minimum wages of other higher-income economies.

Singapore does not have minimum wage in place for its workers. Instead, the country has PAP’s “Progressive Wage Model” (PWM), and Teo said it is an example of being pro-worker. Last year, Senior Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam also said that the PWM is “better than a minimum wage.” However, under the PWM, the base wage that workers earn is only S$1,236 a month.

Singapore ranks among the top 10 richest countries globally in terms of GDP per capita. But if we compare Singapore with other higher-income advanced economies (with GDP per capita around US$35,000 or above), the PWM’s base wage is lower than the minimum wages of these other countries – clearly, the PWM is not better than minimum wage.

In fact, the base wage under the PWM is even lower than the minimum wages of countries with less than half of Singapore’s GDP per capita and is on par with countries with only a quarter of it.

When we compare the minimum wages of these countries against their GDP per capita, it becomes clear how far the base wage of Singapore’s PWM falls far below the trendline – the country’s wealth is not reflected in the wages of workers. In other words, Singapore’s workers are not being returned adequately for the contributions they are making to the economy. The United States, Ireland, and Luxembourg also fall way below the trendline but the high GDP per capita of the latter two countries have a part to play in this. A debate is also ongoing in the U.S. to double its minimum wage.

Critics point to the need to compare wages against cost of living.

But when comparing the minimum wages against the Cost of Living Index as compiled by Numbeo, it becomes even clear that Singapore underpays its workers by a large margin.

Another measure for cost of living is the purchasing power parity (PPP) computed by the World Bank, which uses the price levels of countries to adjust country prices based on their cost of living, for global comparison.

When comparing the countries’ GDP per capita based on PPP, Singapore in fact rises to become the second wealthiest in the world by economic output.

However, when the same conversion is done on minimum wages, the base wage under Singapore’s PWM continues to be among the lowest.

Earlier this month, I wrote about how Taiwan’s minimum wage is already sorely inadequate as compared to the country’s cost of living, but Singapore is worse.

In fact, if Singapore should set a minimum wage that is on par with the minimum rate wages of these other countries based on their cost of living (using Numbeo’s index), Singapore’s minimum wage should be between S$2,000 and S$4,000. Even when using the World Bank’s PPP, Singapore’s minimum wage should be between S$1,500 and S$3,500 to be equivalent to the minimum wages being paid in other countries.

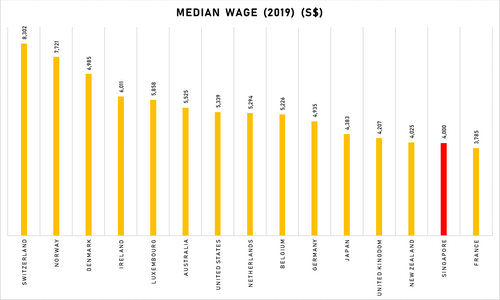

But it is not just Singapore’s minimum wage that is low. When comparing with median wage, Singapore’s middle income workers also earn one of the lowest wages among the highest-income advanced economies. Contrary to what middle-income Singaporeans believe, they are not better off. In fact, they are also being shortchanged of their wages.

The PAP government has long argued that Singapore has a “low-tax regime,” and therefore cannot provide for better social protection. Tharman said in a 2018 interview with The Straits Times that, “the overall tax burden on the average person is much lower in Singapore” than in Western European countries.

However, compared with these countries, Singapore’s average tax wedge, or the total tax and social security contributions that workers pay as a percentage of total labor costs, is not low – it is about 32%. This is actually as high as other higher-income advanced economies.

The tax and social security that workers contribute in other countries pay for social protection, such as healthcare, pension, unemployment insurance, and education. In Singapore, this is in large part covered by the Central Provident Fund (CPF).

Tharman had also said that, “we want to avoid getting to a situation where the average person has the heavy burden of taxes that we see elsewhere,” but the reality is that workers in Singapore already have a similar tax burden than these other countries, when including social contributions.

In fact, last week, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Heng Swee Keat insisted in parliament that, “About half of workers do not pay income tax at all,” and that Singapore’s tax system is designed to be “progressive and fair.”

However, what he omits is that Singaporeans contribute more to the CPF than people from other countries do to their social security schemes for old age. The CPF system is also regressive, in part because CPF contribution for ordinary wages is capped at S$6,000 per month. It means individuals who earn more than S$6,000 will not need to pay CPF for the part that exceeds this amount, thereby resulting in the majority of low- and middle-income Singaporeans carrying the burden of the CPF (70% of Singapore’s workers earned less than $6,000 last year).

Note again that the CPF pays for the same social protection that tax and social security in other countries pay for, and thus needs to be considered as a whole.

With Singaporeans contributing a similarly high average tax wedge as compared to the other highest-income advanced economies, we look at whether Singapore’s workers receive similar benefits.

Based on data from the Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC), I compared the health, pension, and unemployment insurance benefits between Singapore and these other countries.

In the countries covered under MISSOC, most citizens do not pay a single cent when visiting a general practitioner (GP) for basic services. Some countries put a cap on the cost – for example, citizens pay a maximum of S$22 in Norway and a maximum of S$33 in Finland per visit. In Sweden, some citizens do not need to pay a cent, and for others, they do not pay more than S$48. Citizens in France, Latvia, Portugal, and Belgium pay between S$2 and S$10. It is free for citizens in other countries. Medications are free or accounted for separately at a low cost in some cases. In some countries, there is also an annual cap on how much citizens need to pay for healthcare – the cap is as low as S$66 in Finland and S$80 in France, and is about S$360 and S$620 in Norway and the Netherlands respectively, while citizens pay a maximum of S$1,500 for healthcare in Switzerland a year.

In Singapore, there is no cap as to how much patients have to pay, so there is no protection for patients. Based on the 2013 GP Fee Survey, the highest fee per visit to a GP was as high as S$100. This survey was conducted eight years ago, which means fees are likely to be even higher today.

As such, while citizens in most other advanced economies pay tax and social contributions in exchange for free healthcare, Singaporeans instead pay for one of the highest GP fees in the world, if not the highest—even as they contribute one of the highest proportion of their wages into national health schemes in the world.

For hospitalization, it is also free in most countries for basic inpatient services. A fee might be required on a daily basis for some other countries, but in the initial days, this fee is as low as S$4 to S$78 a day.

In Singapore, there is again no cap as to how much patients need to pay for inpatient hospitalization. While the government announced benchmark fees for inpatient hospitalization last year, the fees of S$200 to S$400 is still 2.5 to five times the maximum fee in Finland. Moreover, the government added the caveat that the fees are not a “cap” that has to be “strictly adhered to,” and that “charges that are higher than the benchmarks may not be unreasonable”.

In fact, due to the steadfast questioning of Workers’ Party member of parliament Gerald Giam, it was revealed that in 2012, there were more than 2,400 patients who paid more than S$10,000 for hospitalization, while more than 5,100 people paid more than S$6,000.

While other advanced economies put a cap as to how much citizens have to pay for healthcare, the PAP government instead puts a cap as to how much the government will cover under the country’s Medisave and MediShield health financing schemes.

Again, Singaporeans are paying a similarly high social contribution as citizens in other advanced economies, but are not adequately reimbursed for hospitalization.

The PAP likes to claim that healthcare in Singapore is “affordable,” but in reality, it is one of the most expensive in the world.

In terms of pension, most countries provide a basic or minimum pension for their citizens. In countries with a GDP per capita of more than US$35,000 (which Singapore should be compared with), the basic pension ranges from S$1,300 to S$3,000 a month. For those with GDP per capita lower than US$35,000, citizens still receive a basic pension of between S$200 and S$1,200 – even though these countries have GDP per capita less than half that of Singapore’s.

In Singapore, however, citizens are not guaranteed a minimum pension under the CPF for retirement. In fact, the average CPF payout in 2018 was only S$355 a month while 74% of CPF members, including citizens, received less than S$500 – way lower than the basic pension in the other higher-income countries.

Under a separate Silver Support Scheme in Singapore, a basic payout between S$120 and S$300 a month is provided for elderly Singaporeans, but this is available only for the poorest 20%. Also, S$120 is still much lower than the amount of pension received by people in countries with GDP per capita lower than US$35,000. It is only 4% to 10% the amount in countries with GDP per capita of more than US$40,000.

In 2019, academics in Singapore’s universities calculated that elderly Singaporeans aged 65 years and above should receive a minimum of S$1,379 to have a basic standard of living. The S$120 to S$300 provided under the Silver Support Scheme is only about 10% to 20% of the minimum necessary. The average CPF payout of S$355 is also only a quarter of the basic amount required. Three-quarters of Singaporeans receive only about a third or less the amount after they retire.

In addition, while Singapore’s government still refuses to implement unemployment insurance, governments of other high-income advanced economies provide anywhere between 40% to 90% of a person’s previous wage as unemployment insurance.

In Singapore, the cost of public universities is also one of the highest in the world.

Moreover, while the PAP government keeps harping on providing public housing at “affordable” prices, Singapore’s public flats under the Housing Development Board (HDB) are in fact as expensive as some of the private housing in other advanced economies. Singapore’s wage distribution is similar to that of Italy and Spain, but the prices of HDB flats in Singapore are in fact equivalent to the private property prices in these two countries. In this context, Singapore’s HDB flats are neither “public” nor “affordable.”

Land costs comprise about 60% of the cost of developing HDB flats. It means that these flats are 120% more expensive than they should have been, if not including land costs.

When we compare the prices of 2-bedroom flats, Singapore’s public HDB flats again rank as being as expensive as the private flats in other advanced countries. Notably, in the Netherlands, Ireland, and Belgium, where private flats cost similarly to public flats in Singapore, their minimum wages are more than two times higher than the base wage under Singapore’s progressive wage model. The median wage of Singapore’s middle-income workers is only a two-thirds to three-quarters the median wages in these countries.

The CPF con that Singaporeans pay is on par with the tax and social security contributions citizens pay in other advanced economies. But while most countries provide truly affordable healthcare, adequate pension, as well as unemployment benefits, it is the complete opposite in Singapore – Singaporeans pay for one of the most expensive healthcare in the world, and receive inadequate pension and no unemployment benefits. Singaporeans also pay one of the most expensive university fees in the world, as well as public housing that costs the same as private housing in the other advanced economies.

What is worse, the majority of Singaporeans earn the lowest wage on average among higher-income advanced economies.

In other words, Singaporeans contribute a high amount for social security to the CPF when it provides little social protection. They often have to pay out of their own pockets additional high amounts to receive social protection, which make their already low wages even lower.

The CPF is also being used by Singaporeans to pay for the HDB flats. But if their wages are higher and do not have to pay additional out-of-pocket expenses for social protection, they would have enough in spare cash to pay for housing without depleting their CPF funds. In that case, elderly Singaporeans would also be able to retire today with adequate retirement payouts.

This was also why the Progress Singapore Party’s Non-Constituency Member of Parliament Leong Mun Wai pointed out in parliament last week that, “the current generation in Singapore has to shoulder a disproportionate amount of […] social security costs and has to struggle with a lower level of disposable income giving rise to the phenomenon popularized by Jack Neo’s movie, “Money No Enough.”

Singapore’s social protection system, of which the CPF is an important component, is highly profitable for the PAP government, while Singapore’s workers are being sucked dry of their wages, social security contributions, and then additional out-of-pocket payments.

This begs the question – where have the CPF funds that Singaporeans pay gone to, if not for their healthcare and pension, or even for unemployment benefits or education?

As of the end of 2020, the CPF component intended for retirement (the Ordinary and Special accounts) accumulated a total of S$272.8 billion in balance, but the amount withdrawn for retirement purposes in 2020 was only S$6.4 billion, or only 2% of the total balance. The government’s sovereign wealth fund GIC invests most of the rest of this balance (the CPF monies are channeled into government bonds, and then transferred into national reserves before going into the GIC).

In 2019, the CPF component for healthcare – Medisave – accumulated a total of S$102 billion in balance, but the amount that was withdrawn for direct medical expenses in 2019 was only S$1.1 billion, or only 1% of the total balance. Again, GIC invests most of the rest of the balance.

At the end of 2019, the other health financing scheme, MediShield Life, accumulated a total of S$8.3 billion in reserves, but only S$1.0 billion in claims were paid out in 2019, or only 12% of the total reserves. This is highly unusual as governments in other advanced countries pay out for healthcare with almost all the health insurance premiums collected in a year. Only in Singapore does the government keep so much of the reserves it collects. GIC invests most of the rest of the balance.

The fund also collects the land costs of HDB flats, which comprise 60% of the cost of developing the flats, for investments.

The national reserves are also accessible by Singapore’s other sovereign wealth fund Temasek Holdings.

Today, on the back of the GIC and Temasek Holdings, Singapore ranks as having the 5th largest combined sovereign wealth funds in the world.

While Singaporeans pay a CPF social contribution rate similar to the tax and social contribution rates of the other advanced economies, Singaporeans are not receiving their monies back adequately in terms of healthcare and retirement. Instead, the monies have been used to enrich GIC and could also enrichTemasek Holdings.

The two sovereign wealth funds are governed by Singapore’s prime minister Lee Hsien Loong and his wife, Ho Ching. He is the chairperson of GIC, and she is the CEO of Temasek Holdings.

Also, while Singapore’s workers earn the lowest wages among the higher-income advanced economies, Singapore’s prime minister actually earns the highest salary among political leaders around the world.

And while the base wage under the Progressive Wage Model is not adequate to meet the cost of living in Singapore, Singapore’s prime minister receives far more than what he needs in terms of cost of living.

Evidently, when you drill down into the data, the PAP government is not “pro-worker” at all.

Singapore refuses to implement an adequate minimum wage and provide unemployment benefits.

But while the PAP government collects as much in the name of social protection as other highest-income advanced economies, it also makes Singaporeans pay one of the highest healthcare and university tuition fees in the world and does not provide an adequate pension – all of which can be covered by the CPF contributions that Singaporeans currently pay, if pegged to the other advanced countries.

The reason why Singaporeans are not able to receive adequately for their healthcare is because the PAP government does not place a cap on what Singaporeans have to pay for it as other governments do. Instead, the PAP puts a cap on what the government needs to pay, allowing the balance from the Medisave and reserves from the MediShield to be channeled into the GIC to make profit via a convoluted process of investment.

The reason why Singaporeans are not able to receive adequate pension payouts is because Singapore does not have a minimum pension payout that meets the cost of living like other advanced economies do. Instead, the PAP provides only a basic interest rate of between 2.5% and 4% on the CPF retirement funds, and the excess returns on investment are reinvested into the GIC (of which is accessible by the Temasek Holdings). In comparison, for the 22 largest major markets in the world, the rate of 10-year compound annual returns averaged 6.2% last year. The excess returns not given back to Singaporeans is also known as an implicit tax that Singaporeans are paying.

You could possibly look at the wages not returned to Singaporeans, and the additional out-of-pocket funds Singaporeans pay for social protection (which the CPF should have otherwise paid for) as implicit taxes, too.

Singaporeans are not paying low taxes.

Singapore’s public housing is as expensive as private housing in other countries. It is because the PAP government incorporated land costs at market rate into HDB flat prices in 1985.

CPF interest rates started declining from 1986, until 1999 to stay at a low basic rate of 2.5% to 4%. This process started 40 years ago under the 62 straight years of PAP’s rule, at a time when first-generation PAP leaders were unceremoniously removed from the parliament and their ministerial roles in the 1980s. Then-deputy prime minister Toh Chin Chye had “oppose[d] the pace of renewal in the PAP rank,” on the belief that he “should not be cast aside to make way for technocrats who had been parachuted in.” But after the 1980 general election, Toh was “dropped from Cabinet to pre-empt any leadership split over the issue.” Both Toh and another PAP old guard leader Ong Pang Boon were against Lee Hsien Loong becoming the prime minister.

The data above tells you that no matter what the PAP government proclaims, Singapore’s model is not one to follow – it is based on the exploitation of workers. The PAP’s rhetoric of “affordable” healthcare and housing is empty rhetoric. Living in Singapore is actually very expensive – especially for its citizens who have to contribute CPF.

In effect, Singaporeans are being tied down by CPF mechanisms created by the PAP government to profit.

In fact, Singapore is not pro-worker. If anything, it is pro-GIC and pro-Temasek Holdings, and it is pro-ministers – each of the ministers earn more than any other political leader in the world.

Meanwhile, Singapore’s workers are left to languish.

The PAP is not pro-worker. It is anti-worker.

*Note: Nordic countries and Austria do not have national minimum wages, their wages are collectively agreed together with workers – considerably more “pro-worker” than Singapore. The minimum rate wage used in this comparison for these countries are the base wages negotiated for the hospitality industry. Switzerland follows a similar model where there is no national minimum wage, however a minimum wage was implemented in the city of Geneva last year after residents voted in a referendum to implement one – this comparison uses Geneva’s minimum wage.

READ NEXT: Taiwan’s Economy Is Growing Fast. Workers Still Await Their Share.

TNL Editor: Bryan Chou (@thenewslensintl)

If you enjoyed this article and want to receive more story updates in your news feed, please be sure to follow our Facebook.