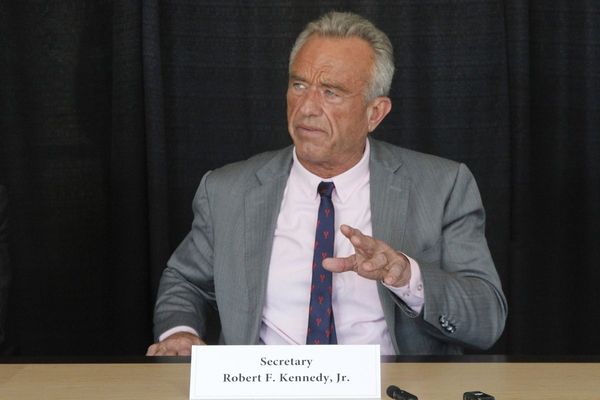

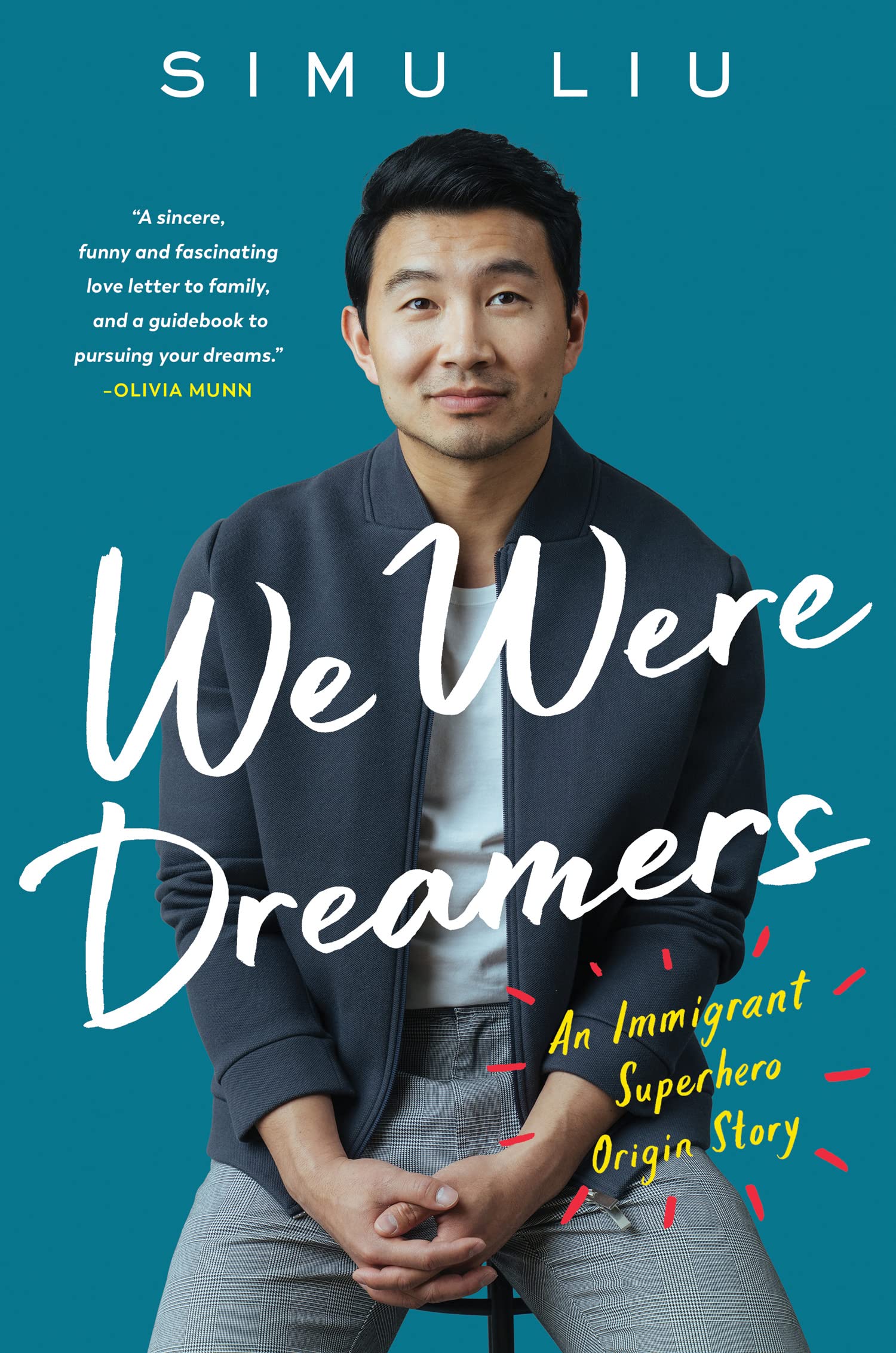

Simu Liu is stumped. It’s noticeable because the Canadian actor, best known for playing Marvel’s Shang-Chi, typically speaks briskly and persuasively. He takes natural ownership of a conversation, steering it like a salesman. I’ve mentioned that his new memoir, We Were Dreamers: An Immigrant Superhero Origin Story, has a subtle theme of atonement to it – for how he’s mistreated girlfriends, how he accelerated his parents’ car straight into their garage door, how he once aspired to live like the stars of Entourage, the US comedy about famous scumbags who date supermodels. It made me wonder. Now that he’s 33 and stable, does Liu like who he once was?

“It’s very hard,” he whispers, eventually. “I don’t think I do. I was constantly aware of how I was being perceived. In my younger years, I was desperate for the admiration of others. Sometimes I would try to say or do things to capture people’s attention, but people would just roll their eyes. It would never work. It’s like being cool in high school. You either have it or you don’t and I most definitely did not. None of the pieces were falling where they should and I hated it. I was a sad kid.”

There are a few reasons why Liu’s candour is surprising. One is that he works for Marvel, a money making juggernaut whose stars tend to keep their quirks and traumas behind closed doors. Another is that Liu is a bit of a mystery, his celebrity having yet to fully form. Last year’s Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, in which he was confident, graceful and quippy – so perfect MCU material – is his only major film to date. His other big projects, including Margot Robbie’s top-secret Barbie movie – he’s rumoured to play a Ken doll – are still awaiting release. In a Hollywood context, Liu is half movie star and half newborn baby. So why a memoir? “So early!” he interrupts. “As I’m holding it in my hand, I can practically hear people saying: ‘But… he hasn’t done anything!’”

We’re speaking over Zoom while Liu is on a break from filming. He’s dressed in what looks like a designer bowling shirt; his hair is styled into a fluffy quiff. It’s more or less the only hair he’s got right now, having recently waxed his body for Barbie. “Waxing has been an education to say the least,” he says. “It was one of the most painful experiences of my life. I have such a newfound admiration for the incredibly brave women who go through this on a monthly basis.” Chatter has suggested the movie is a meta-comedy with shades of The Truman Show, which starred Jim Carrey as a salesman who discovers his life is a constructed TV series about which he’s been kept in the dark. “Honestly, the discourse online is giving me life,” Liu laughs. “With every casting announcement or bit of news, they’re like: ‘What is this?’ And that’s perfect – the less you know about it the better.”

It’s the only thing he clams up about. We Were Dreamers, on the other hand, is a strikingly honest book, its hero a mass of contradictions. Gleeful exhibitionist gripped with insecurity. Mouthy teen capable of great tenderness. Romantic outcast with abs and boy-band hair but never a date. What emerges is a portrait of a young man who spent his childhood despising his parents but now desperately wants to humanise them. In an early chapter, he writes that they provided him with boundless opportunity and professional guidance, but little emotional warmth. “If I got a good mark, they would hardly react,” he notes. “If I got a bad mark, I was berated for being either stupid or some variation of a failure. If I talked back, they would smack me around a little.” What started out as slaps became punches to the face with closed fists. “Our relationship was almost irreconcilable,” he says. “Every single day was torture for me.”

Liu’s harrowing dynamic with his parents makes up the bulk of the book. The actor was born in Harbin, China, in 1989 and raised by his grandparents. His parents, meanwhile, were studying in Canada, attempting to forge a better life. When Liu joined them in Ontario at the age of four, he was practically a stranger. Their excitement over his arrival rapidly gave way to tired complacency. “I felt like I ceased to be an endless burst of joy and became something that had to be molded, or groomed, for success,” he writes. His parents described him as an “investment” who was “squandering all [their] effort and money”. They were disappointed by his poor grades in school, as well as his affinity for the arts. Later he’d end up concealing his attempts to kickstart an acting career, and for months pretended that he hadn’t been sacked for frequent tardiness from his high-paying accountancy job.

What scares me about Twitter is not having control over [the] narrative ... Opinions are formed, accusations can be made, and then you only have 280 characters with which you can respond

Today, Liu is sanguine about it all. “I am not the only person who’s experienced this,” he says. “Ask any child of any immigrant family if they’ve had a heated argument with their parents that sometimes got physical.” He has great empathy for what they went through – newcomers in Canada with no support system and enormous economic pressure. “That’s the immigrant mentality. That’s the panic that runs through all of our parents’ veins. So when you have a child that is threatening to undo all that you’ve worked hard for, you’d be pretty mad. I’m not trying to make excuses for their actions, but I am trying to contextualise them. My parents aren’t villains.”

It’s easy to understand his parents’ fears, and their disappointment over what they saw as their only son going off the rails. The same can’t be said about two adults assaulting and bullying a child. Liu thumbs his chin. “I knew it would be difficult to bring the reader back after that,” he says. “But people change and evolve, and that’s exactly what my parents have done. That’s why I give them as much leeway as I do now. I’m tremendously proud of them for the fundamental leaps and bounds that they’ve made.” In conversations with his parents, he says he can see their regret. “Again, that’s not to make excuses for them, but I know that if they were to go back, they’d do things differently. And for me right now, that’s enough.”

Is the abuse made easier to rationalise, though, because of his success? Liu’s parents never imagined their son would become a Hollywood actor, but they did ultimately get what they’d hoped for: a son who has far surpassed their own incredible achievements. “I understand what you’re saying,” Liu replies. “Basically: do my parents love me more now that I have succeeded?” Well, maybe not quite as blunt as that… “No, I totally get you. I do think it makes everything easier to have experienced success on such an unprecedented level. But I will say, if it had just been that, it would have been a lot harder for us, and I would feel distrustful. But our path to reconciliation started all the way back in 2017.” That was when Liu had just one season of the Netflix sitcom Kim’s Convenience under his belt, and was asked to write about his upbringing for a Canadian magazine. Seeing it written down served as a wake-up call to Liu’s parents, and conversations about their shared history began to take place. “Not in any way had I proven real success [at that point], so I feel like we’re genuine. I don’t have any feelings of doubt.”

We Were Dreamers isn’t entirely depressing. There’s also a lot to laugh at. Liu writes with ingratiating deadpan, encouraging readers to skip chapters and cringing at his own desire to look like NSync’s JC Chasez. But it’s undeniably a difficult read at times, full of complex ideas about sexuality, race and masculinity. He writes of “the total mindf***” of growing up Asian and male, and the media’s tendency to depict men who look like him as “awkward, nerdy and completely undateable”. As a teenager in the early Noughties, he “both resented and admired [the] white bastion of beauty” that defined Abercrombie & Fitch, the hyper-sexualised fashion retailer whose staff were almost exclusively white supermodels-in-training. He ended up working there.

Liu covers his face with his hands. “It’s very embarrassing, but I wanted so badly to be hot,” he laughs. “I wanted so badly to be desired and loved and admired. I had an attention deficiency at home, but also I was probably just a dumb kid who wanted a girlfriend and to be thought of as attractive. I mean, who doesn’t?” Soon after he started work at Abercrombie, he discovered the company had a specific racial quota to fulfil. “And I was part of the quota,” he says. “But at the time I didn’t find it… I mean, I knew it was discriminatory but, like, so was everything else in the world! So was every single movie. It wasn’t like Abercrombie was somehow especially discriminatory. It actually made me feel good to be able to work there.”

He’s more confident about his appearance today. “I don’t feel like I’m the hottest man in the world,” he says, “but what I’m trying to be is a model of self-assuredness. The fun of being topless every once in a while is feeling like… yeah, I worked for this! I deserve to feel good in my skin! And if it happens to shatter a couple of stereotypes along the way, then sure, why not?”

Liu is still navigating his newfound fame. Combined with his busy social media presence, that means occasional Twitter controversy. He was accused last year of misinterpreting a Disney executive who called Shang-Chi’s release strategy an “interesting experiment”. He also faced criticism for signing onto a film with Mark Wahlberg and then deleting an earlier tweet about Wahlberg’s violent assault on two Vietnamese Americans in 1988.

“You don’t know if opinions are coming from real people, or if it’s a targeted attempt to bring you down,” Liu says. “Being a public figure on today’s internet means being a lightning rod for people typing whatever they feel at any specific point in time. What scares me is not having control over that narrative. My nature is to want to clarify, but then the nature of Twitter is to keep it short. Opinions are formed, accusations can be made, and then you only have 280 characters with which you can respond or choose not to.”

He suggests he’s been told to rein in his Twitter use, and to view the platform as more of a “liability than an asset”. But he’s still online, interacting with fans and commenting on culture. “I’m rebellious by nature,” he says. “If people try to get me not to do something, it’s a surefire way to get me to do it.” Just ask the makers of Barbie. Despite being under a gag order when it comes to the film’s plot, he’s revealed all to his parents. “We’ve come so far, and I hate the idea of keeping anything from them,” Liu says, proudly. “They’re my best friends now. And you tell your best friends everything.”

‘We Were Dreamers: An Immigrant Superhero Origin Story’ is out now via William Collins