At the beginning of each episode of Goliath, the well-crafted, three-part Showtime and Religion of Sports docuseries on legendary hoops star Wilt Chamberlain that premieres this Friday, there’s a disclaimer.

“Wilt Chamberlain’s voice in this series is created using an A.I. program with the permission of the Wilt Chamberlain estate. Wilt’s words have been composed of quotations of his written work and public statements,” the statement reads.

Other interesting filmmaking tactics have been utilized before to voice departed legends. An ESPN documentary on former Raiders owner Al Davis and former NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle used deepfake technology a couple of years ago, while a Marlon Brando documentary made use of more than 300 hours of audiotapes the actor had recorded over the years. (The entirety of the Brando doc is in his own words.)

But the best part of Goliath has nothing to do with technology and instead, everything to do with the richness of the storytelling. Chamberlain is a fascinating, larger-than-life character who’s been out of the limelight since his passing in 1999 at the age of 63. In an era when fans have been given shows produced by LeBron James, and entire docuseries on Michael Jordan, Magic Johnson and Bill Russell, it makes sense that Chamberlain—the most dominant basketball force of his time, and perhaps ever—has his incredible story documented for this generation, too.

“He changed the face of basketball,” says Victor Buhler, one of the executive producers of the film. “He wasn’t Jackie Robinson, necessarily. But when you look at someone like LeBron, as a student of the game, he can look at the stardom of Russell or Wilt or Michael. There wasn’t anyone of Wilt’s stature for him to go off of, really. He was figuring it out in real time.”

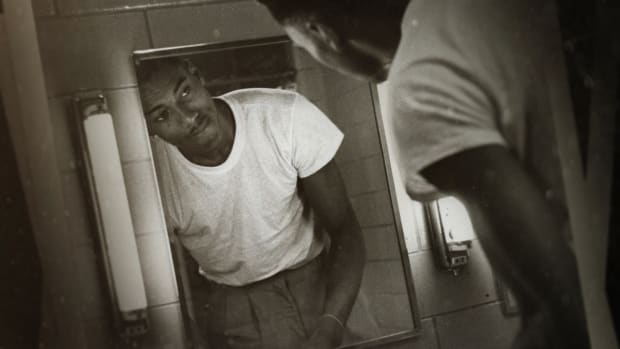

SHOWTIME

George Mikan had been the biggest name in basketball before the era in which Russell and Chamberlain shined. But for all the winning Russell experienced—he won 11 titles despite being far less flashy and talented as a scorer—Chamberlain possessed skills no one had ever seen. Yes, he was the tallest man on the floor, but could also get down the court faster than just about anyone. He had an enormous vertical leap, meaning every opposing shot was liable to get swatted away. Chamberlain developed a silky, unblockable fadeaway jumper, which the doc illustrated looked highly similar to the one Dirk Nowitzki would later make popular all over again. He never ran out of energy on the court, and during the 1961–62 season—one in which he averaged 50.4 points and 25.7 rebounds—managed to play more than 48 minutes per game. (He also put his mind to passing and led the league in total assists once, during the ’67–68 campaign.) Even if Russell’s Celtics teams generally got the best of Chamberlain and his teammates, Chamberlain and his otherworldly dominance were undoubtedly the draw. Their rivalry was one of the league’s marketability linchpins from a television standpoint.

Chamberlain’s life story is compelling, too. As a young boy, he overcame his stuttering and immense discomfort with being abnormally tall by garnering confidence through his athletic dominance. He despised being called “Wilt the Stilt,” and instead preferred to be called “Dip” or “The Big Dipper” because he almost always had to duck his head when walking through doorways, and had an affinity for looking for constellations in the night sky. One of the greatest athletes of all time, he was a track star and played pro volleyball in addition to being one of the strongest basketball players ever. The doc has footage of actor Arnold Schwarzenegger, who was in the 1984 film Conan the Destroyer with the former NBA superstar, being in awe of Chamberlain’s strength. Chamberlain bench-pressed a whopping 500 pounds in his playing days.

As both a Black man and a Richard Nixon supporter—particularly at a time when the Republican party was employing the Southern strategy—Chamberlain certainly wasn’t seen as a civil rights activist in the way Russell was. (Although both men badly wanted to postpone the 1968 East Conference finals game that ultimately ended up being played the day after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated.) But it’d be inaccurate to say Chamberlain wasn’t a pioneer.

The big man was far ahead of his time in knowing his worth as a marquee name. The series points out that Chamberlain, as a star at the University of Kansas, helped desegregate the restaurants in the city of Lawrence, at least during the years when he was a student there. In a move that’s commonplace now—with players leaving high school and college early to play in different pro leagues—Chamberlain left Kansas after his junior year, way back in 1958, to tour with the Harlem Globetrotters instead. He earned $65,000 that year, several times the average player salary in the NBA at the time, and the equivalent of $686,000 today.

Even during his playing days, he signed one-year deals and used the threat of retirement—things James has done at times—to exert outsize leverage over his teams’ management groups. He also said once that he’d fundamentally trade himself if he had to by making things untenable for the Sixers after Chamberlain was denied a share of the team’s ownership. (The superstar said Ike Richman, the Sixers co-owner, his dear friend and personal attorney, had promised him a slice of the club before suffering a fatal heart attack courtside. Irv Kosloff, the other co-owner, said he knew nothing of the vow, and couldn’t honor it, prompting Chamberlain to eventually demand the trade that resulted in his joining the Lakers in 1968.)

In a way, Chamberlain embodied player empowerment long before anyone thought of it that way. Temple professor Marc Lamont Hill, a Sixers fan, referred to Chamberlain as a “solo artist,” often charting out the path best for him, without regard for how it might impact others. Another analyst featured in the film, Hall of Fame writer Jackie MacMullan, said the big man’s approach made sense, given how marketable Chamberlain knew himself to be. “People are treating me like a commodity, so why don’t I act like one?” she said, explaining Chamberlain’s mindset.

He won his first title with the Sixers in 1967, then took another in ’72 with the Lakers as a member of the first true NBA superteam, one that also featured future Hall of Famers Jerry West and Elgin Baylor. The championships, in conjunction with his status as the game’s biggest, most dominant individual force, only elevated his stardom even more, particularly in Los Angeles. He had an almost 9,400-square-foot custom home built in Los Angeles—complete with a retractable roof to look up at the stars he loved so much—that would be the sort of home featured on MTV Cribs decades later with countless NBA superstars.

SHOWTIME

Perhaps the best parts of the series, though, are the ones that humanize him, for better or worse. It digs into Russell’s criticism of Chamberlain—that he’d essentially quit while sitting out the final minutes of Game 7 of the NBA Finals with a twisted knee—and how it wounded him that one of his closest friends would say it. (They made amends decades later.) Several times, Chamberlain’s duality was on full display, leaving viewers to wonder whether he was a chauvinist or someone who did his best to support women the best he could. Was he outspoken and wildly confident, or did Chamberlain have a deeply sensitive side?

Interviews with his family—sisters, nieces and nephews—and close friends cut closer to the core of who the man was. And the answer was complicated, particularly when it came to the way his exploits with women were discussed. His 1991 book, A View From Above, in which he claims to have slept with 20,000 women, happened to come out just weeks before Magic Johnson’s HIV diagnosis was announced publicly, leading some to take Chamberlain to task for perceived irresponsibility. The doc, refreshingly transparent, digs into paternity questions, too.

“When the interviews [about the book] came out, the only thing people heard about was the 20,000 [women],” said Jessica Burstein, a longtime friend. “He was devastated. [Wilt] said, ‘It was a lie, anyway. I don’t know why I did it.’ It did haunt him. He remained upset about that.”

The film comes across as an honest portrayal of one of the true legends in sports—one that will undoubtedly help illuminate a fascinating figure younger generations know less about.