Just one year after then-Immigration Minister Alex Hawke moved to expel tennis star Novak Djokovic from Australia on character grounds, his Labor successor, Andrew Giles, is faced with another controversial visitor in the form of Ye (formerly known as Kanye West).

Although he’s both a musician and rapper, Ye may be best described as a social influencer – and one with very offensive views, especially when it comes to Jewish people and the Holocaust.

Never one to miss a political opportunity, Opposition Leader Peter Dutton, a former home affairs and immigration minister, has declared he would block Ye if he had the power. As media interest mounts, Giles, the minister with the actual responsibility here, has yet to respond. Ye’s prospects and travel plans remain in the balance.

Read more: Why Novak Djokovic lost his fight to stay in Australia – and why it sets a concerning precedent

Denying visas on ‘character’ grounds

Ye’s case centres on the section of the Migration Act that permits the exclusion of people from Australia on “character” grounds. This includes anyone who may “vilify a segment of the Australian community” or “incite discord in the Australian community or in a segment of that community”.

Our current migration laws have been shaped by a long history of high-profile, controversial visa applicants. All of these cases underscore the fact that rights to freedom of speech and expression have never been recognised under the law when it comes to those seeking entry to Australia.

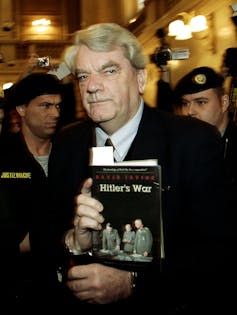

One of the most notable cases involved British Holocaust denier David Irving, whose visitor’s visa was denied in 1993 on character grounds, specifically because he was “likely to become involved in activities disruptive to, or violence threatening harm to the Australian community”.

Irving’s proposed visit drew loud protests from various community groups. His supporters, however, funded challenges to the minister’s decision in the Federal Court. In spite of concerns the laws were creating a “heckler’s veto”, the court found no legal error in the minister’s decision. Irving has since been rejected for a visa a couple more times.

This pattern has been repeated in many other cases, including last year’s decision to cancel Djokovic’s visa due to his stance on COVID vaccination.

A failed dictation test in Scottish Gaelic

Ironically, one of the most famous visitor cases involved an individual who came to Australia to warn people about the dangers of Adolf Hitler and the rise of fascism in Europe.

In 1934, a prominent Czech communist, Egon Kisch, had been invited to speak at an anti-war event in Melbourne. The federal government believed his visit might be used to spread communist propaganda.

There was no “character test” when it came to migration matters in the 1930s, but politicians still played a key role in the admission process.

Instead, the exclusionary device used was the “dictation test” in the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, which prohibited entry to

Any person who when asked to do so by an officer fails to write out at dictation and sign in the presence of the officer a passage of 50 words in length in an European language directed by the officer.

Frustrated by Kisch’s linguistic brilliance – he was fluent in a number of languages – the immigration official resorted to a test in Scottish Gaelic, a language with which neither Kisch nor the officer were familiar. The High Court overturned the decision to expel Kisch on the basis Scottish Gaelic was not “a European language under the act”, fuelling anger in the Scottish community in Australia.

Interestingly, the decision to expel Kisch was made by the newly minted Liberal attorney-general, Robert Gordon Menzies. Menzies had learned of Kisch’s earlier exclusion from Britain and considered this a sufficient reason to follow suit.

Political calculations often play a role

The potential for controversial visitors to espouse offensive views has been a concern for politicians on both sides of the political divide.

However, it does seem conservative politicians have been particularly keen to play the character card. In 1997, for example, the then-acting immigration minister, Amanda Vanstone, decided to cancel the visitor visa of US racial equality activist Lorenzo Ervin. The move followed interventions by outspoken right-wing Senator Pauline Hanson, who complained about Ervin’s criminal past.

Like Kisch, Ervin was imprisoned and released after a successful High Court challenge.

Another US political activist, Scott Parkin, enjoyed less success a decade later when he was targeted for engaging in protests against the US invasion of Iraq. Vanstone (again) cancelled his visa on character grounds and he was removed from Australia.

All attempts to obtain reasons for the decision – or to gain access to his adverse security assessment failed.

Where does this leave Ye’s case?

Where does this leave Ye’s potential trip to Australia? Unlike Irving, Ervin, Parkin and Kisch before him, Ye does not seem to have a public reason for his visit, such as a performance or speech.

Having married a Melbourne woman, he would simply be seeking entry to meet his partner’s family. This may be enough to distinguish him from these earlier cases.

What is clear from previous cases is the fact the immigration minister has long enjoyed extraordinary power to exclude and expel non-citizens whose presence in Australia might prove unpopular. And these decisions inevitably involve political calculations. Just ask Novak Djokovic.

Mary Crock does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.