Vital coastal habitat was destroyed in the devastating floods that hit New South Wales in 2021 and 2022.

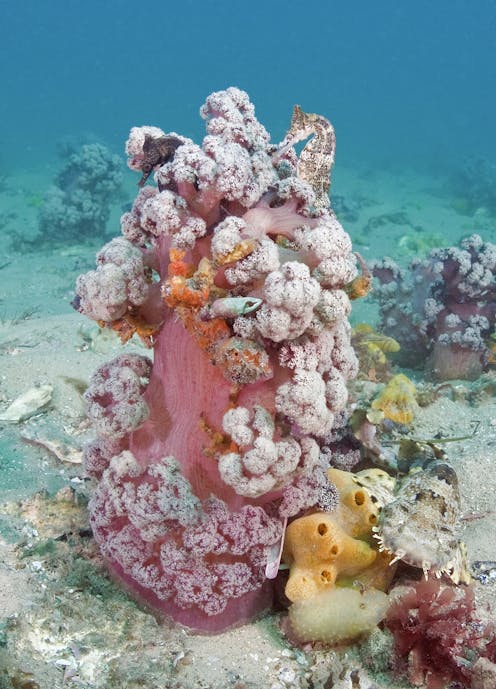

The purple cauliflower soft coral Dendronephthya australis, now listed as an endangered species, was almost completely wiped out in the Port Stephens estuary and along the coast. That’s a tragedy because this coral shelters young snapper and the endangered White’s seahorse.

Unfortunately, a lack of knowledge hampered recovery efforts – until now.

In our new research we discovered how the coral reproduces. We used IVF (in-vitro fertilisation) to create baby coral in the lab. And we successfully transplanted the coral into the wild. This offers new hope for the survival of the species.

Read more: Beautiful, rare 'purple cauliflower' coral off NSW coast may be extinct within 10 years

Variety is the spice of life

Corals have a complicated sex life. There’s more than one way to “do it”. And gender varies too.

Corals can reproduce asexually, meaning they create genetic copies of themselves. This process often entails shedding polyps that can attach to reefs to form new colonies.

Using this process is a common approach for coral restoration. It’s a bit like propagating plants. Cuttings or fragments are removed from adult colonies, briefly maintained in the lab, and then new corals are transplanted into the wild. This isn’t a simple process for soft corals, though we have been exploring ways to make this work for Dendronephthya australis.

Many corals are hermaphrodites, which means they have both male and female reproductive organs. Others form colonies that are entirely male or female. And some mix or swap sexes.

Spawning is the release of eggs and sperm. Again, corals can use various techniques. Broadcast spawning is where eggs and sperm are released into the water column. Brooding is where eggs are fertilised within colonies and later released as larvae.

But until sexual reproduction of an individual species is observed, their sex life remains a private matter.

A chance discovery in the lab

We were growing coral in the lab, raising asexual clones from fragments, when we noticed something unusual.

There were small orange dots inside some of the corals. These were much larger than the grains of dry orange “coral food” we fed them. So they had to be something else.

We soon realised the orange dots were unfertilised eggs. Half of the fragments in our care contained eggs. As sperm is much smaller, we had to sacrifice small portions of the remaining coral fragments for closer inspection of their contents (under a microscope). In doing this, we discovered the other half were sperm-bearing.

As fate would have it, we had collected fragments from two donor colonies – one female and one male. By chance, we discovered Dendronephthya australis is “gonochoric” (meaning colonies are either male or female).

We watched the corals carefully over the following weeks and made more discoveries. Females spawned (released their eggs) around the “neap tide” (when the moon appears half full) during the summer months.

Maybe the coral evolved to spawn when tidal currents are slowest, to maximise the chance of fertilisation.

Coral IVF for making babies

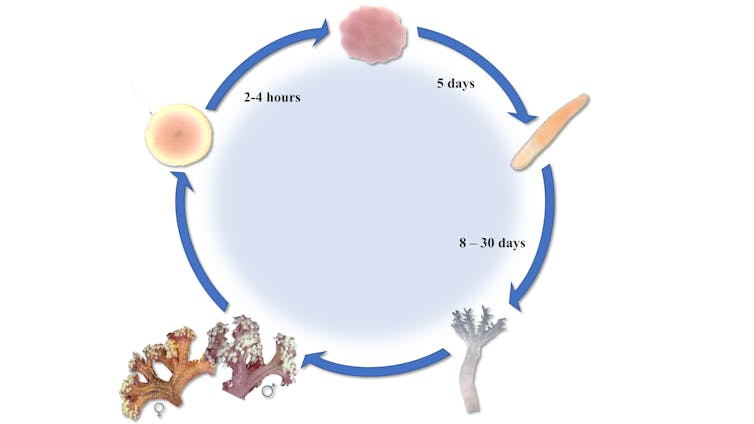

We used IVF techniques to fertilise harvested eggs. Cell division occurred within hours. Mobile larvae grew over the following week.

From eight days of age, the larvae started to transform into polyps; we were the first people to witness these tiny cauliflower coral babies (as single polyps).

Within just a few weeks, we had produced 280 babies from just a few coral fragments.

Understanding how the purple cauliflower coral reproduces is important for several reasons:

maintaining genetic diversity: if the sex ratio becomes unbalanced, the effective population size will be lower than the total number of remaining individuals

achieving fertilisation: broadcast spawning in corals is density-dependent. That means if more colonies are lost, the chance of natural sexual reproduction decreases

restoring gender balance: any attempt to grow more coral from fragments will need to ensure both male and female colonies are represented

scaling up production: sexual reproduction provides an opportunity to raise more baby corals while maintaining genetic diversity in the population.

Ongoing restoration work

Since this discovery, we have successfully repeated these IVF techniques. We transplanted hundreds of coral babies and released thousands of larvae back into Port Stephens.

Early results suggest some IVF babies survived at least the first 18 months and performed better than the asexual fragments.

We plan to implement the IVF program annually. We’re optimistic that we can boost the population of this endangered coral in ways never thought possible.

Read more: Coral, meet coral: how selective breeding may help the world's reefs survive ocean heating

Meryl Larkin receives funding from the NSW Department of Primary Industries, Southern Cross University’s National Marine Science Centre and Marine Ecology Research Centre, and the Australian Government Research Training Program. Ongoing work (subsequent to Meryl Larkin's PhD project) has been supported with funding from the NSW Environmental Trust.

David Harasti received funding from the NSW Environmental Trust to implement recovery actions for the endangered soft coral.

Kirsten Benkendorff, Stephen D. A. Smith, and Tom R Davis do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.